A triple-minded Shakespearean in Japan Many-hatted professor reaches audiences through his research, translations, and plays

On the 400th anniversary of his death, which is being celebrated in 2016, William Shakespeare is once again in the spotlight with no shortage of material being produced for theater, cinema, television, and print (figure 1). While many of us in Japan, far away from Shakespeare’s native England, may know his name, a good number will likely say they haven’t been to the theater to see his plays being performed on stage.

Professor Shoichiro Kawai of the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences has been studying the dramatist for some 40 years, and is the driving force of Shakespeare research in Japan. What sets Kawai apart from other Shakespeare researchers is that not only is he a renowned scholar, he is also a prolific translator—and not just of Shakespeare—and a playwright in his own right.

Nothing gets lost in translation

![Figure 1: Cover of Shakespeare no Shotai

Born in 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon, northwest of London, Shakespeare is a leading English playwright who left behind a number of plays, including Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet. His life is shrouded in mystery, with some saying he was actually someone else. Shoichiro Kawai, Shakespeare no Shotai [The True Identity of Shakespeare] (Tokyo: Shinchosha, 2016).

Figure 1: Cover of Shakespeare no Shotai

Born in 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon, northwest of London, Shakespeare is a leading English playwright who left behind a number of plays, including Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet. His life is shrouded in mystery, with some saying he was actually someone else. Shoichiro Kawai, Shakespeare no Shotai [The True Identity of Shakespeare] (Tokyo: Shinchosha, 2016).](/content/400044042.jpg)

Figure 1: Cover of Shakespeare no Shotai

Born in 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon, northwest of London, Shakespeare is a leading English playwright who left behind a number of plays, including Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet. His life is shrouded in mystery, with some saying he was actually someone else. Shoichiro Kawai, Shakespeare no Shotai [The True Identity of Shakespeare] (Tokyo: Shinchosha, 2016).

“Whereas it is the academic’s job to immerse themselves in their research, I approach my work differently by placing priority on the staging of plays, while my translations and research are a means of reaching that objective,” says the professor. “I ground myself in a comprehensive view by examining past performances, previous translations, and the body of research on a particular work, and incorporating that into the stage production. And the knowledge I gain from the stage in turn informs my subsequent research and translations. My method is a constant repetition of this feedback process.”

For the translator and playwright in Kawai, the rhythm of the original language is critical and something that cannot be overlooked. Rhyme is used frequently in Shakespeare’s works, but conventional Japanese translations, which place a heavy emphasis on meaning, have largely failed in conveying Shakespeare’s rhymes. When Kawai was a university student, while working as an interpreter for a theater group putting on a performance in Toga, Toyama Prefecture—a village in central Japan well known for its theater events—he was struck deeply by the performance of renowned Japanese stage actress Kayoko Shiraishi during rehearsal. Ever since that experience, Kawai has watched actors up close breathing life into their lines with their soul, prompting him to consider it his calling not only to place importance on the meaning of the words, but also on how they are expressed. In his recent translations, he has rendered all the rhymes of the original English into Japanese.

“It’s an arduous process. Sometimes, I’ll spend all night trying to think of a good translation and come away empty-handed. However, I consider it my duty—as one who has tackled Shakespeare from the avenues of research, translation, and performance—and I am prepared to carry out my mission” (figure 2).

The culmination of Shakespeare research

Kawai has compiled the fruits of his, as it were, “trinity” of activities into a book for general audiences entitled Shakespeare: Jinsei Gekijo no Tatsujin (Shakespeare: Master of the Theater of Life), published by Chuo-koron Shinsha in 2016. For example, Kawai describes the interesting parallels between the notion of “Shakespeare magic,” which bends time and space, and similar qualities in kyogen traditional Japanese comic theater. Unlike modern drama, which makes heavy use of props and sets, Shakespearean drama doesn’t even use a curtain—all that occupies the stage are the actors. Everything is left to the audience’s imagination.

“The opening chorus of Henry V contains the line, ‘Think when we talk of horses, that you see them.’ This is just like in kyogen when the actor circles the stage and utters, ‘By mere mention of it, whoa, we have landed in the capital,’ and the audience leaps through time and from one place to another with just that one line. The notion that the actors and the audience sharing the same space is the essence of drama is alive and well,” says Kawai.

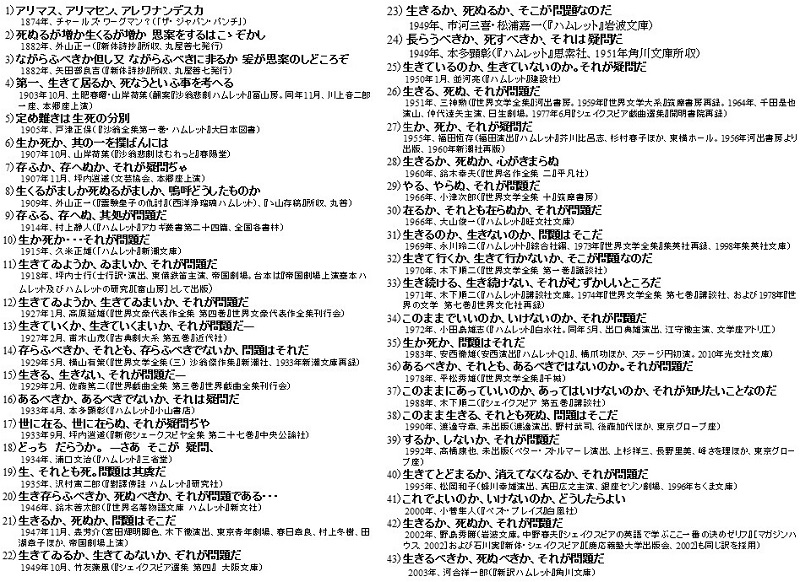

Figure 2: 43 different Japanese translations of the famous line from Hamlet, “To be, or not to be, that is the question.”

After finding 42 different translations of the line in his research and considering their merits, as a translator and a playwright, Kawai settled on his own translation of the line: “Ikiru beki ka, shinu beki ka, sore ga mondai da.” (Shinyaku Hamlet) (Hamlet: A New Translation), Kadokawa, 2003. Although this is now the standard rendering, it had never been used until Kawai translated the play.

As implied by the phrase “myriad-minded Shakespeare,” while the Bard’s true identity remains the subject of debate, Kawai offers a variety of approaches to better understand and appreciate Shakespeare—whether through the context of the deep religious strife that existed between Catholics and Protestants in Elizabethan England; or that his tragedies can be viewed as illustrating the struggle faced by those seeking justice who must choose between “this or that,” and his comedies show how a diverse group of people can, in the end, accept both “this and that”; or that there is a mirror which reflects the truth as seen by the “eye of the soul,” and drama functions as that mirror in reality… . The professor’s commentary is packed with these and other perspectives for a thought-provoking discussion. Ever since he discovered Shakespeare through the radio program Hyakumannin no Eigo (English for Millions) when he was in his second year of high school, Kawai has been an avid student of Shakespeare for 40 years. His book packs the fruits of his labor over four decades and presents them as an introduction to his research rather than a collection of essays.

Shakespeare research throughout the ages and the world

Figure 3: Cover of As You Like It

Kawai recalls, “When I was in high school, I liked English, so I read As You Like It in the original English. My partner in crime saw me reading it and said, ‘That’s porn, isn’t it?’ I replied, ‘No, it’s an English book,’ and showed him the cover, and he said, ‘Yeah, right.’ For some reason, I remember that exchange like it was yesterday.” After The Comedy of Errors plays at the Owl Spot theater in Higashi-Ikebukuro, Tokyo, in September 2016, a new translation and staging of As You Like It, a work for which Kawai has fond memories, may be his next project.

In the past, Shakespearean researchers were concerned mainly with interpreting his works. Contemporary research, on the other hand, deals more with how Shakespeare has been received in different countries, and his influence on their cultures. Kawai’s work follows this latter approach.

Now, 400 years after Shakespeare’s passing, should you delve into his works, or should they pass you by? Now that you know about Kawai and his book, this writer is tempted to proclaim that the answer is clear…or at least it should be. But as Kawai, a master of Shakespearean drama, would say with a smile, “As you like it.”

Interview/text: Jiro Takai

*Top page photo: Scene from Titus Andronicus during 13th Shakespeare series performance at Sainokuni Saitama Arts Theater in Saitama City, Japan. (Courtesy of Sainokuni Saitama Arts Theater; photo by Chigusa Takashima)

Links

Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

References

Shoichiro Kawai. Shakespeare no Shotai [The True Identity of Shakespeare] (Tokyo: Shinchosha, 2016).

Shoichiro Kawai. Shakespeare: Jinsei Gekijo no Tatsujin [Shakespeare: Master of the Theater of Life] (Tokyo: Chuo-koron Shinsha, 2016).