Restoring Fukushima Agricultural experts pool their resources

Researchers at the University of Tokyo Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences are providing assistance to the region affected by the March 2011 accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. Specialists across a spectrum of fields volunteered immediately after the accident to help revive the area’s farming industry. They continue to conduct on-site survey and research work in close concert with local residents.

Doing something for local communities

“As a researcher on agriculture, I wanted to—had to—do something useful.” Professor Tomoko M. Nakanishi of the Laboratory of Radio-Plant Physiology, Department of Applied Biological Chemistry, says the feeling only grew stronger in the days following the Great East Japan Earthquake and nuclear accident of March 2011. “Agriculture is the mainstay of Fukushima Prefecture. I’m sure that everyone working in the agricultural sciences felt the same way.”

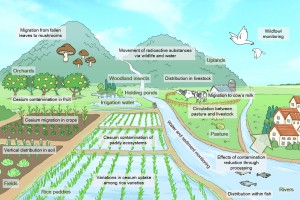

Figure 1: Multiple research themes.

Group surveys are conducted at various agriculture-related sites to study such topics as the adsorption of cesium to soil, its migration from soil to crops, the contamination of wildlife and livestock, cesium runoff from uplands, its absorption by mushrooms, and rice paddy decontamination methods.

© Riopopo.

On April 15, 2011, about a month after the earthquake, Professor Hiromichi Nagasawa, then Dean of the Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences (GSALS), sent an email to all faculty members, urging them to initiate survey research in support of the areas affected by the nuclear accident. Not a few scholars were already doing so of their own volition, and over 50 people promptly responded. Field-specific groups were formed and proposals drawn up for studies of soil, water, woodlands, rice, fruit, fish, livestock, and so on. Under the overarching theme of “reclaiming agriculture from radioactive contamination,” Professor Nakanishi coordinated a unified effort by the entire graduate school that rapidly gained momentum (Figure 1).

The volunteer spirit was infectious. People headed for Fukushima as soon as they could. Research funding could be dealt with later; what was crucial was to start acquiring accurate data on conditions—notably the dispersion of radioactivity—that were changing from moment to moment. Thus began an intense relationship with Fukushima in which researchers continued to visit and communicate with local communities on a regular basis, even while maintaining their own workloads at the university.

Radioactive materials binding to the soil

Of numerous findings obtained through this research, one deserving particular note was confirmation of how readily radioactive cesium was adsorbed onto the soil in Fukushima. “It was like pollen with superglue,” says Professor Nakanishi. Airborne cesium emitted by the accident was immediately adsorbed upon contact with the surface of the soil of Fukushima, after which very little of it was taken up by plants.

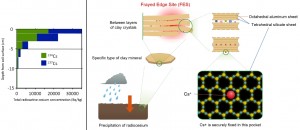

Figure 2: Cesium distribution in soil.

Cesium has a tendency to be fixed in the layered crystalline structure of clay minerals. It was found that most cesium remains in the first 5 centimeters of soil below the surface.

© University of Tokyo.

Of all the radionuclides released by the Fukushima Daiichi accident, cesium is and will continue to be the one with the greatest impact. Not only was radioactive cesium emitted in relatively large quantities, but nearly half of it was cesium 137, an isotope with a long half-life of about 30 years. Half-life is a specific value for a given radioactive substance and denotes the period of time it takes for its radionuclides to be reduced by half.

In on-site studies conducted shortly after the accident by Professor Sho Shiozawa of the GSALS Laboratory of Land Resource Science, it was found that most of the cesium was distributed to a depth of around 5 cm from the soil surface, and adhered particularly to fine-grained clay and organic matter (Figure 2). Also, measurements at the bottom of irrigation ponds into which water flowed from uplands suggested that cesium adhering to fallen leaves was subsequently bound to the soil as the leaves decomposed, and that there was consequently minimal runoff of cesium from the uplands.

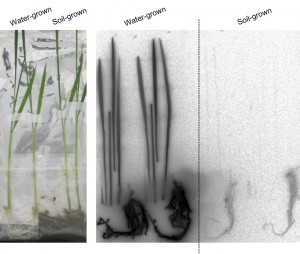

Photo 1: Comparison of cesium uptake in soil-grown and water-grown rice.

Soil-grown rice with roots extended into the soil did not absorb cesium even when the soil and the water in contact with it contained cesium. In contrast, water-grown rice, without soil around its roots, did absorb cesium contained in the water contacting the roots.

© Natsuko I. Kobayashi.

Professor Nakanishi and Associate Professor Keitaro Tanoi of the Laboratory of Radio-Plant Physiology worked with then-Assistant Professor Norio Nogawa et al. of the University of Tokyo’s Radioisotope Center to perform experiments on the contaminated soil. In one experiment, they tried washing the soil: the first washing removed about 20 percent of the cesium, but subsequent washings yielded virtually none. They also studied differences in the amount of cesium absorbed by rice grown in the laboratory in water and in soil, and found that whereas the roots of water-grown rice absorbed cesium dissolved in the water, hardly any cesium was absorbed by soil-grown rice. This is because the cesium was bound to the soil (Photo 1). These findings were supported by the 2012 tests on all rice grown in Fukushima Prefecture, which detected no radioactivity whatsoever in 99.8 percent of the inspected rice.

The adsorption of cesium to the surface of soil is a phenomenon that was seen in surveys following the Chernobyl nuclear accident of 1986 as well as the nuclear weapons tests of the 1960s. But the clayey soil of Fukushima showed a “higher than predicted speed and strength of adsorption,” says Associate Professor Tanoi.

Professor Nakanishi points out that unlike heavy metals such as mercury and cadmium, known for causing environmental pollution-related illnesses in the past, cesium “shows virtually no tendency to leach and disperse from soil via water, or to concentrate in organisms.” To deal with such substances, one has to understand them from a scientific standpoint. Determining the distribution and movement of a contaminant like cesium is the first step in figuring out how to proceed with decontamination.

Decontamination with agricultural producers in mind

The research group’s motto is “on-site”?in the sense of going to the source, not doing one’s work from a distance. From the outset its members have worked closely with local producers, nonprofit groups, and local governments. They have talked and listened till late into the night, worked and sweated together as they wielded hoes and shovels alongside farmers in the fields. Precisely because of this experience, they have sought to devise decontamination methods that would have the least negative impact on local soil fertility.

Professor Masaru Mizoguchi, a soil physicist, collaborating with the local nonprofit group Resurrection of Fukushima, has come up with a method that involves irrigating rice paddies with water, agitating the surface of the submerged soil, then sweeping the muddy water, which contains the fine soil grains to which cesium has adhered, into a ditch dug nearby. The accumulated cesium binds to the bottom and sides of the ditch and remains there, effectively trapped.

Farmland is a production site, and the soil is a precious production resource that has been nurtured over decades and centuries. To strip and discard thick chunks of topsoil, or subject it to high-temperature or chemical decontamination, deprives fields and paddies of nutrients and microorganisms that are essential to agricultural production. With producers in mind, the researchers feel a powerful obligation to preserve and protect the soil.

Disseminating accurate data

The findings and data obtained from this research are being disseminated to the public. Since September 2011 GSALS has held briefings every three or four months; the eighth such meeting took place in December 2013. These briefings afford researchers an opportunity to present their findings and the audience to get answers to their questions.

Agricultural Implications of the Fukushima Nuclear Accident, an English-language compilation of papers by researchers involved in this project, was published by Springer in 2013. With the aim of providing as many people as possible with the most accurate data possible, the work is open-access; in the first four months of online publication it was downloaded over 10,000 times. A Japanese-language book authored by Professor Nakanishi, Dojo osen: Fukushima no hoshasei busshitsu no yukue [Soil contamination: tracing radioactive substances in Fukushima], has also been published by NHK Books. Through these briefings and publications the researchers hope to provide accurate information to the world at large on conditions in Fukushima, as well as contribute to the study of radioactivity-related issues by future generations of students.

From the basics of agricultural science to the future of Fukushima

What made this widespread dissemination of information possible was the volunteer spirit that inspired it. Researchers promptly shared the latest data with Fukushima citizens, further deepening the bond of mutual trust with local people. Among the researchers, too, “there was a feeling that we could all talk to each other whenever problems came up,” says Associate Professor Tanoi. Because everyone was on the same page, so to speak, the entire graduate school pitched in and a collaborative mood quickly took hold.

Photo 2: Farm at a survey site in Fukushima.

The research produced significant results thanks to an “on-site” philosophy that fostered a relationship of mutual trust with local farmers.

© Keitaro Tanoi.

The farming and fishing industries exist in a mutual relationship with numerous aspects of the natural environment. Research in these areas necessitates close interaction with the sites of production, producers, and consumers. The ambitious project to reclaim Fukushima agriculture from radioactive contamination proved to be an opportunity for researchers to get back to the easily-neglected basics of agricultural science. What began as a volunteer effort has gradually gained financial support in the form of research funding. But, Professor Nakanashi avers, “in keeping with the Japanese spirit of cherishing our farmlands, we intend to stay firm in our commitment to serve local communities first” (Photo 2).

While shipments of agricultural produce from Fukushima are recovering, it is not that easy to alleviate the anxieties of consumers. Nor is the full picture of the impact of radioactivity in the soil on local agricultural producers clearly understood. There are other issues, too, that confront Japanese agriculture at large, notably the aging of producers and a shortage of successors to the farming business. Solving these problems may require the development of new, more sophisticated systems of production.

“My hope is that we can achieve a future in which the people of Fukushima no longer need to worry about the effects of the nuclear plant accident, and can focus on an ‘agricultural renaissance’ in the fullest sense,” says Professor Nakanishi. Speaking on behalf of the entire research group, she declares, “Our ultimate mission is to persevere in our support of agriculture in Fukushima.”

References

Tomoko M. Nakanishi, Dojo osen: Fukushima no hoshasei busshitsu no yukue, Tokyo: NHK Books, 2013.

Tomoko M. Nakanishi & Keitaro Tanoi (eds), Agricultural Implications of the Fukushima Nuclear Accident, Tokyo: Springer, 2013.

Researchers

Professor Tomoko M. Nakanishi, Associate Professor Keitaro Tanoi

Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences

Laboratory of Radio-Plant Physiology