Toward Active Living by a Centenarian Generation A Large-Scale Social Experiment for a Highly-Aged Society

By the year 2030, Japan will be a “highly-aged” society in which one person in three is 65 or older. In anticipation of this future scenario, the Institute of Gerontology at the University of Tokyo is designing and testing models for communities in which senior citizens can not only enjoy active lives, but work and contribute to the overall health of Japan’s economy as well.

Limitations of the 60-Year Lifespan Infrastructure

Japanese enjoy the greatest longevity of any nation on earth. By 2015, 25 percent of the population will be 65 or older, and by 2030 the figure is expected to exceed 30 percent. Moreover, 60 percent of these senior citizens will be 75 or older, and about half of them will be living alone. Particularly in urban areas, the number of single elderly is thought to be growing fast.

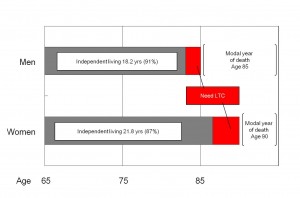

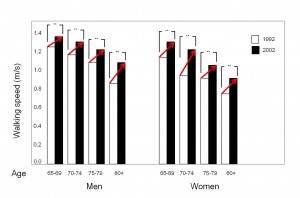

If you are a Japanese person celebrating your 65th birthday, you can expect to have about 20 years of a “second life” ahead of you if you are male, and 25 years if you are female. Both men and women will require nursing care for about one-tenth of that second life, meaning that they will be capable of living independently for as much as nine-tenths of their remaining years (fig 1). If we compare the typical walking speeds of senior citizens in 2002 and 1992, we find that 75-year-olds in 2002 walked at the same pace as 64-year-olds a decade earlier (fig 2). In other words, both men and women have grown 11 years “younger” in terms of physical health during that period.

“But Japan’s social infrastructure is built on the obsolete model of a sexagenarian society, one predicated on a 60-something life expectancy. According to this model, people are expected to retire from their jobs at age 60, to be supported from that point on by the younger generation. This worked fine in the days when 60 was the mandatory retirement age and everyone lived out their remaining years in pretty much the same way. But today, people are still working at 60, and they can look forward to an ever-broadening palette of life options beyond that age. If we are going to deal effectively with the highly-aged society of the future, we must come up with a new life design for people living into their nineties, or even their hundreds.” So says Project Professor Hiroko Akiyama of the Institute of Gerontology.

A 25-Year National Survey of the Japanese Elderly

Professor Akiyama studied gerontology in the United States, conducting research on aging for many years at the University of Michigan, a major center of gerontological studies. Still in its nascent stage when she first traveled to America, the field came of age as an academic discipline precisely during the same period that Japanese society’s aging process was beginning to accelerate, thus affording her an ideal opportunity to observe the phenomenon from an overseas vantage point.

In 1987, while working at the University of Michigan, Professor Akiyama launched the National Survey of the Japanese Elderly, a panel study of seniors throughout Japan. Sampled at random from the nationwide Household Registry, 5,715 residents of Japan age 60 or older were visited every three years and interviewed in person to track changes over time in their physical and mental health, economic status, and social relations.

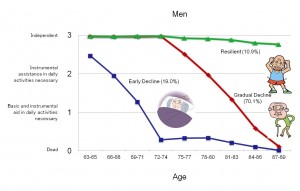

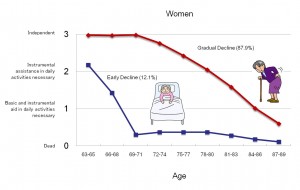

Over the course of this survey, which has continued for 25 years, Professor Akiyama’s attention was drawn to the point at which the independence of men and women over 70 begins to decline (fig 3, fig 4). Her thinking is that we must build a social infrastructure that will at least somewhat postpone this point of decline — in other words, that will prolong the period of independent living, including productive work, by the elderly. Moreover, we must develop a living environment that allows the elderly to “age in place” — to continue living in a familiar locale where their quality of life (QOL) can be maintained even if they live alone or their physical or mental health declines. This, she believes, is the cornerstone of a new approach to life design for a centenarian society.

A Social Experiment in Kashiwa

Since establishing the Institute of Gerontology in 2009, the University of Tokyo has taken an active role in addressing the issues associated with an aging society. Under the directorship of Professor Junichiro Okata, also of the Graduate School of Engineering’s Department of Urban Engineering, the Institute provides an interdisciplinary platform for collaborative work by researchers from a spectrum of fields, including medicine, nursing, engineering, psychology, sociology, economics, law, and education.

Under the overarching theme of “redesigning communities so that residents can age in place,” the Institute has initiated a number of research projects on the design of communities conducive to a long-lived society. One such project involves a large-scale social experiment in the Toyoshikidai district of Kashiwa City, Chiba Prefecture.

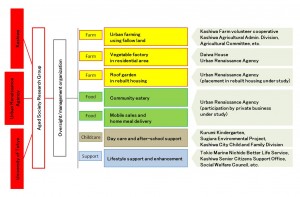

First developed as a bedroom community just outside Tokyo in the early 1960s, Toyoshikidai is a typical residential suburb of the metropolis, with a mix of condominiums and single-family houses surrounding the 5,000-unit Toyoshikidai Danchi apartment complex, interspersed by parcels of farmland. In collaboration with Kashiwa City and the Urban Renaissance Agency, the project has already begun construction in this rapidly aging neighborhood of a senior-friendly community that includes not only shops and medical and nursing facilities, but also workplaces for the elderly (fig 5). The aging apartment complex is in the process of being replaced with 10- to 14-story apartment houses designed to facilitate single living by seniors.

At the center of the neighborhood will be a “Community Eatery,” a dining hall that caters not only to seniors but also to younger residents stopping in for breakfast on their way to work, or children looking for a snack en route to school or club activities. There is data indicating that seniors living by themselves rarely eat home cooking and consequently tend to be undernourished, a condition that exacerbates their health problems. The Community Eatery is an essential tool for extending healthy lifespans by providing seniors with nutritionally balanced meals in a comfortable setting with other members of the community.

Workplaces for a Second Life

Another priority of this community is providing workplaces for seniors. Over 80 percent of seniors responding to a government questionnaire said that they would like to work after retirement; and in fact, they still have the physical capacity to work. However, the current social infrastructure, which treats the period after retirement as the “sunset years” of one’s life, effectively discourages retirees from working. The National Survey of the Japanese Elderly reveals that the decline in physical independence is particularly pronounced among seniors living alone who have minimal contact with family or neighbors.

Workplaces for the second life must derive, not from corporate social responsibility (CSR) measures, but from successfully functioning businesses. Such work will become available only through the establishment of a framework that makes hiring the elderly a smart business decision for companies. Numerous corporations in the agriculture, food preparation, day care, and livelihood support sectors are already participating in the Toyoshikidai project by setting up new businesses to hire seniors. The project is noteworthy for the diversity of working environments it offers. The agricultural sector, for example, ranges from full-scale farming of previously fallow land, to relatively light work in a “vegetable factory” using indoor shelf-style hydroponic cultivation, to a roof garden accessible to the wheelchair-bound. Thus seniors can choose work suited to their state of health and their own personal preferences (fig 6).

“Seniors vary in their backgrounds and health, as well as in their values regarding work,” Professor Akiyama observes. “If we accommodate this diversity by offering them new workplaces and workstyles with a wide degree of freedom, I believe that the healthy elderly can continue working indefinitely.”

The Institute has also launched community-building projects similar to that of Kashiwa in Fukui City, Fukui Prefecture and Otsuchi Town, Iwate Prefecture. The issues and resources found in these regional localities differ from those of a suburban area like Kashiwa; hence a regional model is being developed for the Fukui project. Otsuchi presents a special case because, as one of the coastal towns that lost its entire infrastructure to the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami, it must rebuild from zero. Therefore the Otsuchi project entails incorporating the senior community into a larger rebuilding vision for the entire town.

In 2009 the Institute launched a University-Industry Consortium on Gerontology in concert with members of the corporate community. Some 60 major companies from the automotive/machine, electrical, food, distribution, construction/real estate, IT, mass media, education, finance, and medical industries have participated. One outcome has been the joint preparation of a “Business Roadmap for a Highly-Aged Future in 2030.” Many corporations view the advent of a highly-aged society as a new business opportunity, and further anticipate that knowhow acquired in Japan can be exported to other Asian countries who will be undergoing their own accelerated-aging period a bit later than Japan.

Professor Akiyama describes the significance of the Institute of Gerontology in this way: “The Institute is a venue not only for interdisciplinary collaboration among Todai scholars, but also for cooperative efforts on an equal footing among corporations, government agencies, and local citizens. We provide a platform on which all these players can actively discuss how to build communities together, and then put their ideas into practice.” From her base at the University of Tokyo, she continues to work toward her goal of putting a new social infrastructure in place by 2030, one that will let all of us lead vigorous, fulfilling lives at an advanced age.

Project Professor Hiroko Akiyama

Project Professor Hiroko Akiyama