How conflict minerals end up in Japan Researcher digs into links between human rights crisis in Congo and consumers in Japan

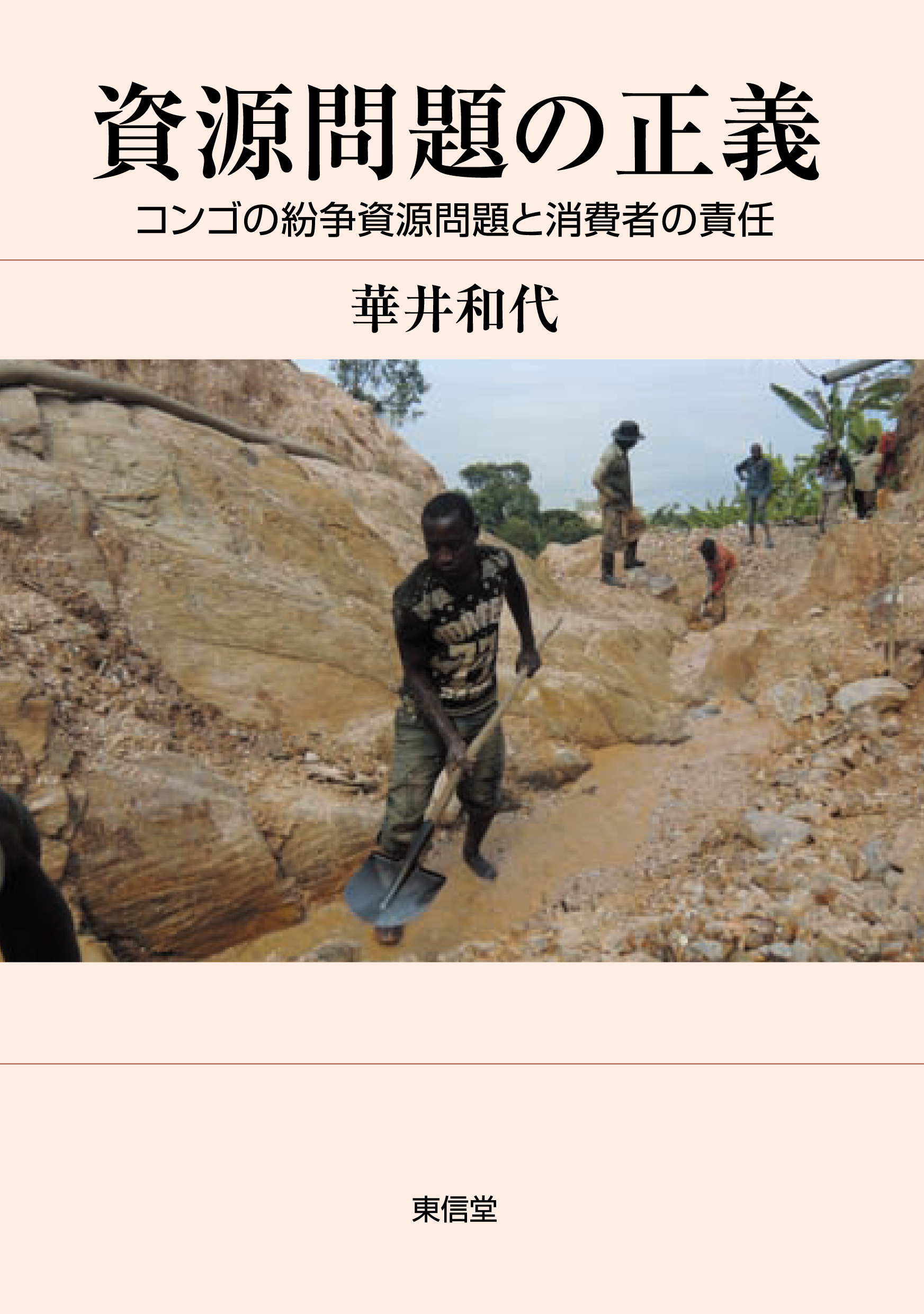

Miners scoop mud in a tantalum mine on Idjwi Island in the Democratic Republic of Congo. © 2018 Pacific Asia Resource Center.

This year’s Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Iraqi Yazidi activist Nadia Murad and Congolese gynecologist Denis Mukwege for their fearless efforts to fight sexual violence in conflict.

The media in Japan — thousands of kilometers away from Iraq and the Democratic Republic of Congo — reported the news of the award extensively, albeit with much less fanfare than when a compatriot wins a Nobel.

Policy Alternatives Research Institute Assistant Professor Kazuyo Hanai ©2018 The University of Tokyo.

But has the news translated into any concrete action by ordinary citizens in Japan, many of whom feel physically and emotionally detached from the country? How could you make them see that they might in fact be contributing to the human rights crisis and compel them to help end or alleviate the problem in Congo, which a United Nations official once called “the rape capital of the world”?

Questions like these have dogged Kazuyo Hanai, an assistant professor at the University of Tokyo’s Policy Alternatives Research Institute. Hanai studies the links between the myriad stakeholders of Congo’s mineral trade, particularly that involving tantalum, tin, tungsten and gold, which have long been tied to conflicts in the country and attacks on citizens living close to the mines by armed groups and government forces.

Congo is said to hold a majority of the world’s reserves for tantalum, a rare metal used in a wide variety of parts for everything from mobile phones and other electronic devices to rockets and missiles.

Concurrently serving as deputy leader of the Association on Sexual Violence and Conflict in the DR Congo (ASVCC), a Tokyo-based civic group, Hanai played a key role in inviting Mukwege to Japan in 2016 to give public lectures, including one at UTokyo.

During the UTokyo lecture, Mukwege — who had already ranked high on the media’s watch list for the peace prize — gave an emphatic speech on how sexual violence in Congo is closely connected to conflicts among the country’s armed groups and their violent quests to gain control over natural resources.

A “weapon of war“

Even mines that have been certified "conflict-free," like the one pictured above, are facing falls in mineral prices. ©2018 Pacific Asia Resource Center.

For nearly 20 years, since he established the Panzi Hospital in 1999, Mukwege has performed tens of thousands of reconstructive surgeries for women, girls and even babies victimized by perpetrators of sexual violence. He stressed that sexual attacks — which often cause severe physical injuries — are used not only to inflict terror on the victims but also as a “weapon of war” to destroy their families and communities.

“The global economy needs natural resources, but they are sourced from the poorest countries,” he said, speaking in French to a packed crowd during that October 2016 lecture at the university’s Ito Hall.

“The mining of minerals is systematically connected to sexual violence. The violence is not motivated by sexual desire; it is a means of terrorism.”

Hanai said she found Mukwege’s talk deeply inspiring.

“I was moved by his unwavering will to end the violence,” she said. “The victims have suffered unspeakable atrocities and have been taken to the doctor’s hospital for surgeries and other care. The experiences the victims have gone through are so horrifying that you come very close to losing hope in humanity. Despite living right in the middle of all this, Dr. Mukwege remains convinced that things will change for the better. I wonder where his strength comes from.”

The situation over Congo’s mineral trade has improved greatly since 2010. That year, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development called on businesses to implement measures to exclude minerals tied to conflicts from their supply chain. But it was Section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Act, the financial reform signed into U.S. law the same year, that really changed corporate behavior by mandating companies listed on U.S. stock exchanges to investigate their supply chain for resources and file reports with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission on their efforts to avoid funding conflicts.

Today, mines in Congo meeting certain criteria — such as not having ties to armed forces or militaries and not using children and pregnant women as sources of labor — are certified and designated as “conflict-free.”

Tantalum is extracted from an ore called coltan, which is shown in this photo. ©2018 Pacific Asia Resource Center.

Japan has no laws regulating the use of conflict minerals, but Japanese companies engaged in business with publicly traded companies in the U.S. are required to comply with American law.

This, however, has led to a situation in Japan where only the business community is keenly aware of their compliance requirements and corporate social responsibility, while consumers at the very end of the supply chain are oblivious of the situation in Congo and the role they might be playing, however indirect, in the conflicts there, Hanai said. The same goes for the Japanese media, whose coverage of the country’s human rights issues pales in comparison to that of the Western media, she added.

“In terms of public awareness, I feel Japanese people are 10 laps behind others in the rest of the world,” she said. “It is only the businesses that are trying hard to keep up with the global community. The consumers and the media are completely in the dark.”

Persisting problems

Since the introduction of international monitoring schemes, armed groups have withdrawn from more than 80 percent of Congo’s mines for tin, tantalum and tungsten, which is a huge improvement, Hanai said.

Despite this, sexual violence against citizens remains rampant, experts say. According to reports by the United Nations Population Fund, the number of sexual attacks in conflict areas of Congo surged from 2,593 in 2016 to 5,783 in 2017. Experts are divided in their views on the increase of the attacks.

But Hanai points out that the number of armed groups has in fact increased, as cash-strapped bandits have split into smaller units. They now raise funds by blocking roads with rocks and charging tolls for vehicles, she said.

In addition, Hanai notes that these days, perpetrators include not only members of the armed groups but also those serving in the country’s military and police force.

A still shot of Dr. Denis Mukwege from the 2015 documentary film “The Man Who Mends Women.”

“Soldiers of armed groups who surrendered to the state have been retrained to serve the country and integrated into the military,” she said. “But the retraining program has not been thorough enough to really change their behavior.”

Furthermore, the living conditions of local residents have become worse. According to a recent report from a village near a mine, the mortality rate of infants rose to 140 percent of the level before the monitoring scheme was introduced. Hanai points to the lack of livelihoods for locals as a factor contributing to the deterioration of the situation.

“It’s good that the mineral trade has become more transparent,” Hanai said. “But we are at a stage where we need to think about how to help locals make a living.”

In addition to further researching the links between Congo’s mineral trade and conflicts, Hanai says she wants to remain active in the ASVCC. The group hopes to soon set up a fund in Japan so citizens can support Mukwege’s efforts directly, she said.

“Trying to change the Congolese situation from Japan is extremely difficult. But thanks to Dr. Mukwege, we now can do our part in helping to find solutions. He is a huge presence for us in that sense, too.”

Interview/Text: Tomoko Otake

- Video of Mukwege’s speech at UTokyo in 2016 (Todai TV, lecture given in French, with Japanese subtitles)

- Screening of “The Man Who Mends Women,” a 2015 documentary about Mukwege, in French with Japanese subtitles: Nov. 27, 2018, at Sacred Heart Global Plaza in Tokyo

Related links

- Policy Alternatives Research Institute

- Association on Sexual Violence and Conflict in DR Congo (Japanese)