Casting a spotlight on Tohoku salmon Researcher's quest to reveal the fish's value from multiple angles

Salted salmon are dried under the sun in Otsuchi, Iwate Prefecture. The salt-cured fish, called Aramaki salmon, has been processed in this fashion across the prefecture for centuries. Photo courtesy of Yuki Minegishi.

Grilled salt-cured salmon is a must-have item on a typical Japanese breakfast menu. Hokkaido is well-known domestically as the No. 1 producer of salmon in Japan.

But Iwate Prefecture in the country’s northeastern region of Tohoku also has a big salmon industry. The prefecture logged the second-largest haul behind Hokkaido, the big island to its north, with a coastal catch of nearly 9,000 tons during the latest season through February 2019.

Yet, a lot about the salmon in Tohoku is unknown.

Professor Jun Aoyama at the Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute (AORI)’s International Coastal Research Center (ICRC) in Otsuchi, Iwate Prefecture, together with other researchers at the center, is studying salmon along the prefecture’s Sanriku coast, with hopes of shedding light not only on the ecology of the popular fish but also on how they have intermingled with people’s lives over the years.

Before being posted to the Otsuchi research center in 2014, Aoyama spent a good part of his academic career studying eel. He won a literature award for essays detailing his thrilling, backpacker-style journeys into the remotest regions of the world, trying to collect specimens of rare eel species for research.

Salmon, another type of migratory fish, sparked his interest one day during his commute to the Otsuchi center, where he saw up close how salmon spawned en masse in the local river.

“It was the first winter after I was posted here,” recalled Aoyama during a recent interview at the center, built on a slope overlooking Otsuchi Bay. “I got out of my car and was gazing at salmon swimming up the stream. Then the fish started spawning right in front of my eyes. They came all the way back from the Bering Sea (the northernmost part of the Pacific Ocean sandwiched between Russia and the U.S. state of Alaska), and they were laying their eggs right here. I found them so endearing.”

Tohoku salmon versus Hokkaido salmon

Jun Aoyama, professor at the Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute’s International Coastal Research Center

Aoyama, who grew up in Yokohama, southwest of Tokyo, and was unfamiliar with the northern parts of Japan before his move to Iwate, says he had had no particular interest in salmon in Tohoku; in fact his images of salmon were all connected to Hokkaido, whether they be the iconic wooden sculptures of brown bears holding salmon in their mouth, or Ishikari-nabe, a salmon hot-pot dish from Hokkaido’s Ishikari area north of Sapporo, he recalls.

“While I’m no expert in folklore studies, I did some research and found that, while many salmon-related folklores exist in Japan, a lot of them concern the indigenous Ainu people. I felt there’s room for research on the relationship between the non-Ainu people of Tohoku and salmon.”

That’s where Kenji Yoshimura comes in. Yoshimura, previously at The National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka Prefecture, has been a postdoctoral researcher at the center since 2017. He has been studying the history and present-day state of salmon-human relationships in Tohoku.

Yoshimura and other researchers at the center have found that salmon in Tohoku are important not only from an economic perspective; they have also been in extremely high demand culturally and socially. Through local rituals and gift-giving customs, salmon have long contributed to the establishment of community ties, according to Aoyama.

Aoyama is also interested in the ecological features of Tohoku salmon that are different from those found in Hokkaido salmon.

In Japan, techniques for artificially hatching salmon made huge advances in the 1970s and the volume of salmon catches has surged. All of the salmon caught in Japan today are artificially produced. But the technical know-how on salmon farming was developed entirely in Hokkaido, and a lot remains unknown about salmon in the Tohoku region, Aoyama said.

“In Hokkaido, big rivers run into the ocean and their water is extremely cold in the winter,” Aoyama said. “On the other hand, Iwate’s coastlines have long, narrow inlets creating many small bays. A lot of small, steep rivers flow into the ocean, and the water is relatively warm, partly because it is mixed with spring water. The ocean and river environment of Hokkaido and Tohoku is very different. Salmon under such different environments cannot be behaving exactly the same way, and it’s clear that salmon in Hokkaido and Tohoku are different in many ways. In hatchery stock enhancement, farmers have repeated the cycle of capturing fish as they swim upstream, extracting their eggs, then artificially inseminating the eggs to hatch baby salmon, which are released into the rivers. But we might be able to develop other techniques that better suit Tohoku salmon.”

In fact, because coastal rivers in Iwate are so short, salmon, full-grown and ready to spawn by the time they reach the mouth of the river, have lost most of the fat in their body, says Aoyama; in contrast, because the distance between the mouth of the river and the gravel bed where the salmon spawn is so long in Hokkaido, the fish caught near the ocean retain a lot of fat.

The less fatty nature of Tohoku salmon explains why its version of the salted and sun-dried Aramaki salmon, which boasts beautiful amber hues with umami (savory taste) trapped inside, tastes so good, he added. Aramaki salmon has been a delicacy across Iwate since the Edo Period (1603-1867).

Researchers at the center are studying how both artificially and naturally hatched young fish weighing just 0.5 to 1.5 grams swim down the rivers in Iwate, travel thousands of kilometers north to the Sea of Okhotsk in the northwest Pacific, the Bering Sea, and even to the North Pacific, then make it back to the prefecture’s rivers about four years later. The researchers are investigating the fish’s journey in various ways, including by attaching small “bio-logging” sensors on their backs.

The team hopes its research will prove useful to Iwate’s fishing industry, which was hit hard by the 2011 quake and is still on its way to recovery.

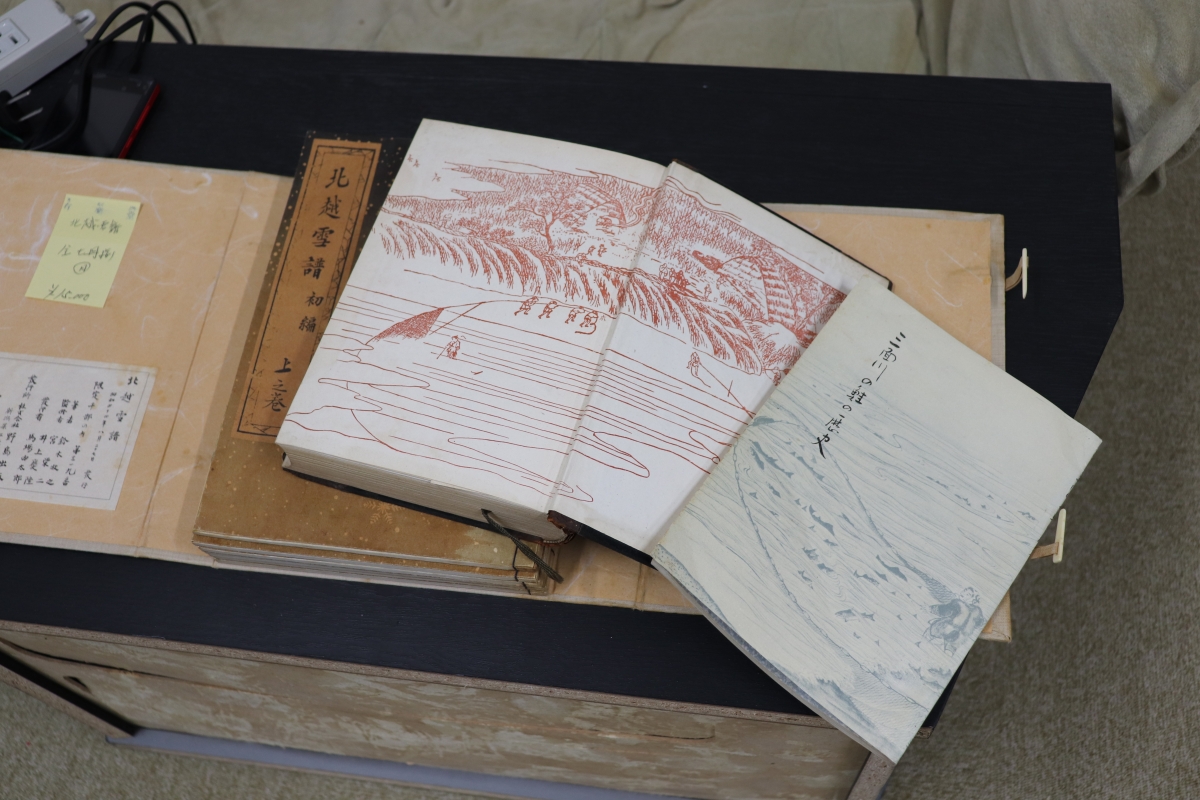

Books on the history of salmon in Tohoku kept in a research lab at the ICRC.

A mature salmon swims in a river in Iwate Prefecture. Photo courtesy of Tatsuya Kawakami.

A painting on the ceiling of the ICRC’s entrance lobby features numerous aquatic animals, including salmon. The work was created by artist Maki Okojima.

Swimming with salmon

Recently, a nonprofit organization in the city of Ofunato, south of Otsuchi, held an event for tourists, where people in wetsuits went underwater in the river to watch salmon swimming upstream.

Aoyama was actively involved in the 2018 launch of the community education project School for Marine Sciences and Local Hopes in the Sanriku Coastal Area, together with UTokyo’s Institute of Social Science. He says he wants to explore the multifaceted value of salmon, through their folkloristic and ecological features and as a tourism resource, and suggest new ways of utilizing the fish in the local community.

“Aramaki salmon, for example, tastes better if you know the story behind it,” Aoyama said. “If we could sell salmon with such a story, at a high value, instead of selling large quantities of them cheaply, it is good for the environment, too. Such stories can also be a source of regional pride. I would like to reconstruct the value of salmon, including its cultural aspects, with the goal of proposing new ways to make use of biological resources.”

Horai Island, in Otsuchi Bay close to the ICRC. A lighthouse on the island, reconstructed after being knocked down by the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, is a symbol of regional recovery.

Interview/Text: Tomoko Otake