Views on Life and Death and Ethical Viewpoints of Those Living Today Come to the Fore in People’s Stories | UTOKYO VOICES 006

Views on Life and Death and Ethical Viewpoints of Those Living Today Come to the Fore in People’s Stories

At around the age of four, Norichika Horie thought to himself, “Why was I born?” He says that at that time he had a kind of revelation, which was to “live to make people happy.” “Perhaps it is not normal to think such things,” says Horie. “However, when I look back, from that time to the present, I see that I have continued to think about what human happiness is.”

When in junior high school, he read works by the German writer Hermann Hesse. This led to an interest in the psychologist Carl Jung. He read psychology books in high school, and began to wonder if religious explanations of phenomena such as faith and spirit possession could be integrated with psychological explanations.

While at university, he discovered the psychoanalyst and sociologist Erich Fromm. He majored in psychology, and became aware of a field of study called the psychology of religion. At graduate school, he was taught by Susumu Shimazono, a professor of religious studies, and wrote his doctoral thesis under his supervision.

While a student, there was little interest in death and life studies among those around him, and the general thought was that religion was meaningless if it did not influence humans’ way of living and was just concerned with funerals and such. “From my interest in spiritual things, I had the vague notion that death and life studies was important; however, I felt there was a limit to how far I could study it when I had no experience of death and life. Even so, I continued to research the theory and philosophy of death and life studies. After a death in the family, the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred. That was the moment when I became serious about the field.”

At first, Horie went to the disaster area to provide support. While there, people who had lost loved ones spoke naturally of the spirits of the deceased. He thought he must research this and, together with a researcher from Tohoku University, he listened to stories from 100 people, and wrote a paper. The biggest discovery he made was that there were two kinds of stories: fearful ones about unknown spirits, and heartwarming tales about spirits of loved ones.

“From regions in which communities have been shattered, there were many stories of spirits that were unable to rest in peace. On the other hand, in regions where temples and graves are located upland and were thus unharmed, and where bonds between people remained strong, when people heard of a spirit appearing, they would ask ‘Where? I want to go and see it.’ The dead were considered as residents.”

He also encountered people who said “The dead have not gone anywhere. They are here.” “The survivors are not just living, they are living along with the deceased. Through hearing such stories, I began to think that everyone has a view on life and death and an ethical viewpoint which should be told, and I wanted to shed light on those beliefs.”

Afterward, Horie interviewed 100 participants in the anti-nuclear demonstrations, and continued to collect and analyze the data. Recently, he has been examining the values and life stories of those who provide care in situations where death and life are in close proximity.

He says that after the Great East Japan Earthquake, the number of people drawn to involvement in activities to help others greatly increased. On the other hand, there are those who criticize people in a weakened state, believing they are responsible for their own situation. Society is divided into polar opposites on this point. “Why do people want to help others when there is no benefit for themselves? Care of those whose existence is threatened naturally connects with issues raised in death and life studies. How is the character of a person who helps and cares for others formed? That is my main research theme at present.”

In 2011, Horie wrote the book Spirituality no Yukue (The Whereabouts of Spirituality) (Iwanami Shoten). “I interviewed young people with an interest in the issues of death, life and spirits; that is, spirituality. Many of them do not talk about it with their friends. They are afraid of their friends pulling away, or of being bullied. Looking back, I see that I was similar. Having someone make a counterargument is fine, but not even being able to talk about it is strange.” Horie wants to create a society in which talking about the important issues of ways of living and ways of thinking is normal.

His quest to discover what human happiness is continues.

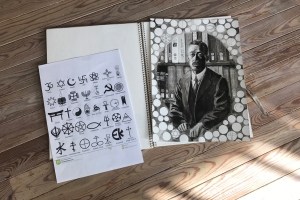

Portrait (work in progress) of the religious scholar Masaharu Anesaki, drawn by Horie. Anesaki entered the Philosophy Department, Faculty of Letters, Tokyo Imperial University in 1893, and studied under Tetsujiro Inoue and Raphael von Koeber. In 1904, he became a professor at Tokyo Imperial University, and in the following year established a religious studies course. He built the foundations for the development of religious studies and research in Japan.

“I made a haiku of a phrase from The Little Prince. Even people who do not follow a faith place importance on what cannot be seen, such as love, spirit and life. The desire to discover more about this drives my research.” [Text: Taisetsu na koto wa sono me de mienu mono ("What is essential is invisible to the eye").]

Norichika Horie

In 1995, Horie completed the Master’s program at the Graduate School of Humanities, The University of Tokyo. In March, 2000, he withdrew from the Doctoral program at the same institution having completed the coursework. From 2001 to 2013, he was a full-time Lecturer and Associate Professor at the University of the Sacred Heart. In 2008 he became a Doctor of Literature at the Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology, The University of Tokyo. Since 2013, he has held the post of Associate Professor at the Center for Death and Life Studies and Practical Ethics, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology. He has written Rekishi no Naka no Shukyo Shinrigaku (Psychology of Religion in History) (2009) and Spirituality no Yukue (The Whereabouts of Spirituality) (2011). His research themes are spirituality and views on life and death. In the future he intends to extend his research to cover intergenerational justice and future ethics.

Interview date: December 19, 2017

Interview/text: Hiroshi Kikuchihara. Photos: Takuma Imamura.