Why does the Brain have a Visual and an Auditory Cortex, but no Time Cortex? | UTOKYO VOICES 028

Why does the Brain have a Visual and an Auditory Cortex, but no Time Cortex?

“Can you prove that the world I see is the same as the world others see?”

Many are stunned to hear that Associate Professor Yotsumoto first asked herself this question when in kindergarten. She vividly remembers that moment. Obviously she could not see into the future, but those doubts are connected to her current research, which aims to reveal mysteries through behavioral experiments and brain activity measurements.

Yotsumoto chose the Psychology and Sociology course, specializing in psychology, as she was interested in how eyeball cells are formed and how that could tell us about why we see the things the way we do. She threw herself into her undergraduate thesis, thus missing job-seeking opportunities, so decided to go on to graduate school. This happened again when studying for her Master’s, resulting in her studying for a Ph.D.

Yotsumoto has a cat-like curiosity, chasing everything that crosses her path and piques her interest. She finds the ensuing tangle of puzzles fascinating, and it was the puzzle she encountered in childhood that led her to become a researcher and attempt to unravel it.

Yotsumoto wrote her doctoral thesis on the human memory, using a mathematical model to investigate how we memorize the things we see. “Using noise that varied over time, I mathematically defined how images seen by subjects become blurred in the memory. I developed a theory of how the memory works by making mathematical formulas of people’s memories.” As a result, she was able to show how memories interfere with each other, and how they become inaccurate over time.

Yotsumoto felt that since her research was theoretical, it wouldn’t have what it took to attract an audience at academic conferences. To overcome this, she undertook behavioral experiments and measured brain activity to shed light on the process by which various kinds of information are processed and integrated in the brain as perception and awareness.

What currently interests Yotsumoto the most is time. “Why do fun times pass so quickly? How does the brain recognize time?” We have sensory organs (eyes and ears) which detect images and sounds, and there are visual and auditory cortexes recognized by the brain: however, there is no sensory organ that detects time and no specific part of the brain known as a time cortex. It really is a mystery.

“It is a fascinating but complex problem. Basically I discovered that we can perceive time by the whole brain, not just parts, working and communicating, as an interaction that includes visceral senses.” In other words, the brain detects and is aware of time as part of an overall network linking nerves, including visceral organs. Future research may lead to the discovery of a mechanism we can only dream of at the moment by which fun times get to feel longer and painful times shorter.

“This topic is interesting in that researching it links directly to our day-to-day perceptions and feelings. Even with small topics, it is fun to think about mysteries for the first time and it’s exciting to be able to experiment and solve mysteries.”

Yotsumoto’s goal in life is to derive more value from experience. “I want to do things I haven’t done before and be able to look back and say that I had a fun life full of all sorts of experiences.” Her dream is to nurture first-class researchers. And in the five short years since establishing her own laboratory (Yotsumoto Laboratory), two of her students have already been awarded the President’s Award for Academic Achievement.

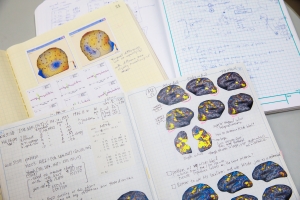

It is easy to forget about data stored on PCs, so Yotsumoto records her ideas and thoughts in A4 notebooks. She has filled up 20 such notebooks. She tells her students that it is important to put their ideas on paper, in chronological order. Her notebooks are useful for answering students’ questions when she can’t always answer from memory.

[Text: “No Data No Right”]

“Basic research is not possible if you are trying to be useful. Investigating the minor mysteries in front of your eyes links to new discoveries,” but nothing is possible without data. “Researchers talk using data; data is life. Researchers who cannot produce data have no right to talk about anything.”

Yuko Yotsumoto

Yotsumoto graduated from the Faculty of Letters, the University of Tokyo in 1998. She studied overseas, at Brandeis University Graduate School, Massachusetts, and earned a Ph.D. in psychology in 2005 based on research into the visual memory mathematical model. Yotsumoto worked as a research fellow at Boston University, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Harvard University, researching brain functions using MRI. Following a position at Keio University as a project associate professor, in 2012 Yotsumoto joined the Department of Life Sciences at the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences as an associate professor (current position). Her awards include the Presentation Award from the Vision Society of Japan in 2000, and the Presentation Award from the Mathematical Psychology Meeting in 2004.

Interview date: January 19, 2018

Interview/text: Tsutomu Sahara. Photos: Takuma Imamura.