60 years of studying society's hidden disparities Sociologists science people's intuitions

In Japan these days, issues about social inequalities and the growing gap between rich and poor are more frequently discussed than before. We've probably encountered various situations where we've felt a sense of inequality on a daily basis. Since 1955, sociologists in Japan have carried out the National Survey of Social Stratification and Social Mobility (SSM), collecting data that allow researchers to examine the mechanism generating social inequalities as well as to see how they have changed over the years. Conducted every 10 years, the seventh survey was completed in 2015 involving well over a hundred members comprising not only senior and young sociologists, but also graduate students around Japan. The survey's findings suggest that what we think and imagine based on our daily life and experiences regarding social inequalities is not necessarily the same as what researchers found based on their rigorous analyses of the empirical data.

The gaps have neither widened nor narrowed

Just as land formations are made up of multiple strata with different characteristics, social stratification theory holds that societies are made up of multiple layers of social classes or statuses.

"How freely a person can move from one social level to another based on achievement, not on his or her parents' social status, allows us to look at how open the society is and see whether it is becoming more, or less, equal," says Professor Sawako Shirahase of the University of Tokyo's Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology. "Conventional wisdom says that it's easier for the child of a doctor to become a doctor. But if the data show that the likelihood of the children of factory workers becoming doctors is the same as that for the offspring of doctors, it provides some grounds for saying that society becomes equal based on the relative chance of intergenerational mobility."

Researchers who study social stratification assess the social status of parent and child based on certain attributes of their work positions such as occupation, employment status, managerial position, and firm size. The great strength of the SSM survey lies in its facility allowing researchers to look at detailed retrospective data about the work history of respondents, aged 20 to 69, starting from the first job they ever held until their current position at the time of the survey. The data can be used to calculate the mobility rate over the life course of individuals or between respondents and their parents, and discuss the pattern and the trend in mobility within and across generations to assess the extent of social inequality.

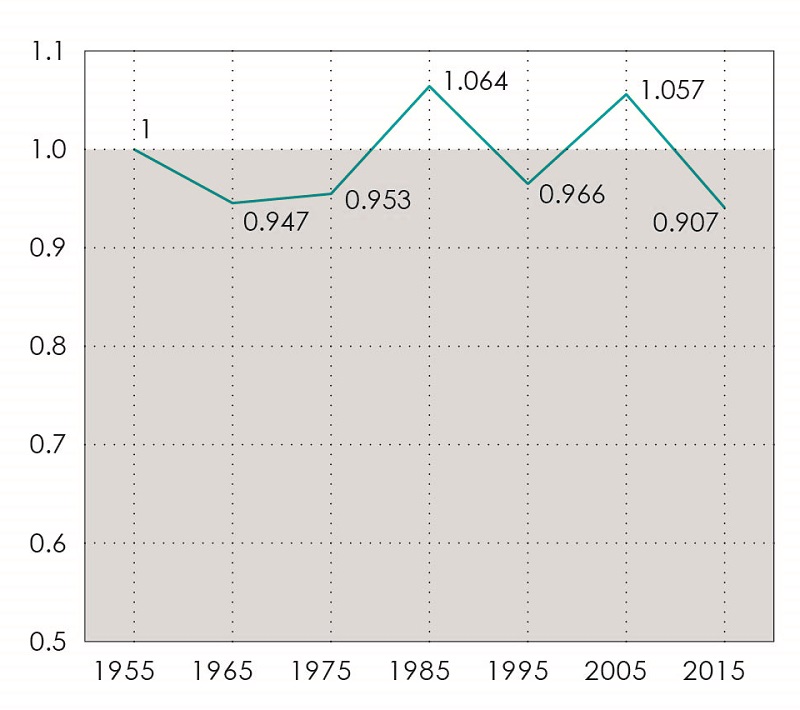

Figure 1: Levels of mobility among classes (relative mobility)

With 1955 as the baseline (1.0) and taking into consideration the change in occupational distributions across time, the graph plots whether the intergenerational associations between social classes of fathers and sons has grown stronger (a rising value implies society has become more closed and more unequal) or weaker (a falling value implies society has become more open and more equal). According to the graph, there has been very little variation in the degree of class associations between generations over the years, and the extent of social inequality based on class mobility has remained more or less unchanged.

Source: As calculated by Hiroshi Ishida based on Hiroshi Ishida and Satoshi Miwa, Kaiso Ido kara mita Nihon Shakai (Intergenerational Class Mobility and Japanese Society), Shakaigaku Hyoron (Japanese Sociological Review), 59 (2009) 648–662, Table 3, and 2015 SSM survey data (v. 050a).

© 2017 The University of Tokyo.

For example, taking into consideration how occupations have changed since the mid-1950s, sociologists can assess the extent to which society has become equal or unequal based on the findings of intergenerational mobility—reflected by the strength of class ties—of the 2015 survey data. According to the results, researchers found that there was virtually no change in the relative class affinities of parent and child, and social stratification has remained more or less stable over the years. That is, when the overarching social transformations that have occurred since World War II are taken into account, the level of social inequality from the perspective of intergenerational mobility has not changed much in any particular direction (figure 1). As in the children of doctors often becoming doctors, the tendency in which children in general remain in the same social class as their parents, and this pattern of the child inheriting the parent's social status has stayed more or less consistent throughout the postwar period. Similar phenomena have been confirmed in the United States and Europe as well.

Does equalizing education decrease inequality?

What can be done, then, to promote greater class mobility and reduce inequality? One possible answer may be education.

"There is an idea that if all children, regardless of their parents' social status, are given equal educational opportunities, their individual abilities could lessen the degree of social inequality," says Professor Takayasu Nakamura of the Graduate School of Education at the University of Tokyo.

At the same time, there are some experts who argue that because the high schools that students attend could significantly affect the subsequent education and career of individuals, they may actually play a role in increasing inequality. So Nakamura set out to examine whether or not high schools could in fact play a factor in increasing the inequality.

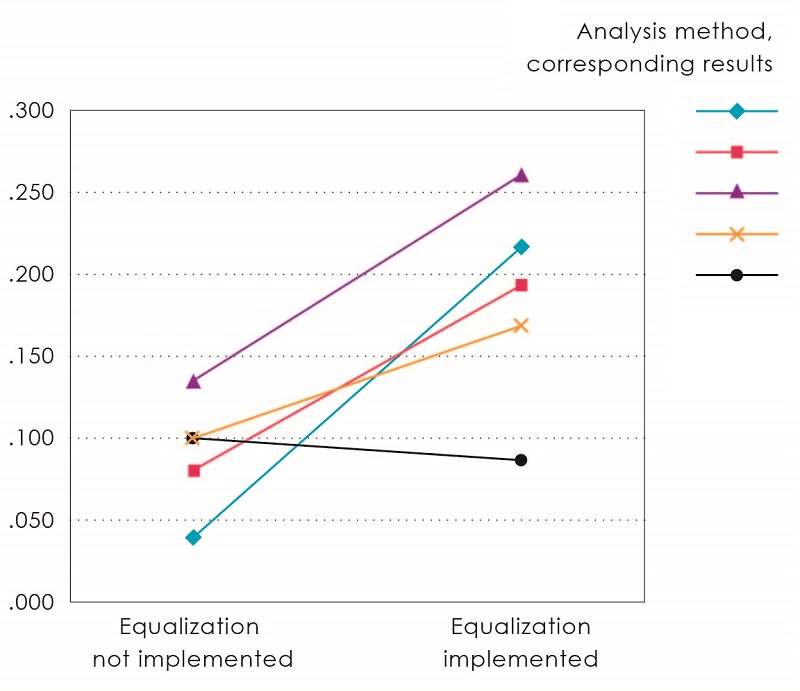

Figure 2: High school equalization policy and college matriculation rates

The lefthand value indicates the influence of social class on college matriculation patterns for students who attended high schools where the equalization policy was not implemented, while the righthand value indicates the same for students who attended schools where the policy was put in place. Multiple different statistical analyses (represented by different-colored symbols and line segments) generally agree that the latter group showed a greater influence of social class in their matriculation patterns.

© 2017 The University of Tokyo.

In his study, Nakamura looked at data from both Japan and South Korea. Here we will focus on the Korean results, which are more comprehensive. During the 1970s, the Korean government implemented a high school equalization policy in certain parts of the country. The plan established a school district system under which the location of a student's home determined where he or she went to high school—much like the system that exists for public middle schools in Japan. Nakamura compared the social ranks and college matriculation patterns of students who attended schools in areas where the equalization policy was in place with those of students from areas where the policy had not been implemented and the choice of high school was still theirs to make.

For the hypothesis to hold up, the college matriculation patterns of students who attend high schools that have not been equalized should reflect a stronger class influence than those of students who attend schools that have been equalized. But the results showed exactly the opposite: The matriculation patterns for the latter group displayed a much stronger class influence. Thus, where one goes to high school did not promote inequality as much as many had instinctively expected (figure 2).

The meticulous work of many

To examine the extent to which the inequality we instinctively feel in our gut exists, and to gauge how much things have changed over the years, SSM team members base their analysis of the survey data on statistical methods.

"It's because we gather detailed data on the occupations of both parent and child that we can speak with a degree of authority," says Professor Shin Arita of the Institute of Social Science at the University of Tokyo who studies the data for what it reveals about the labor market.

Figure 3: 2015 SSM survey questionnaires

The questionnaires contain some 90 questions, including those covering work history—from one’s first job until his or her job at the time of the survey, counting periods of unemployment. The 2015 survey had 7,817 respondents, comprising men and women between the ages of 20 and 79 residing in Japan (valid response rate 50.1 percent).

© 2017 The University of Tokyo.

Following the basic framework of the SSM survey, more than 100 investigators visit respondents’ households with questionnaires to fill out. The investigators listen to and record responses about the detailed work histories of thousands of respondents and their parents (figure 3). Such detailed information about job histories, sometimes containing more than 10 changes in employment, are logically checked, categorized, and coded to occupational titles by the research project team.

"For the most recent survey conducted in 2015, it took more than two whole weeks in which all members of the project worked intensively to clean the data and code occupational titles; we then need to go over all the data again to correct errors," says Arita. "Only by being meticulous at every step can you build the kind of data set that will reveal things you didn't know."

The 2015 SSM survey and beyond

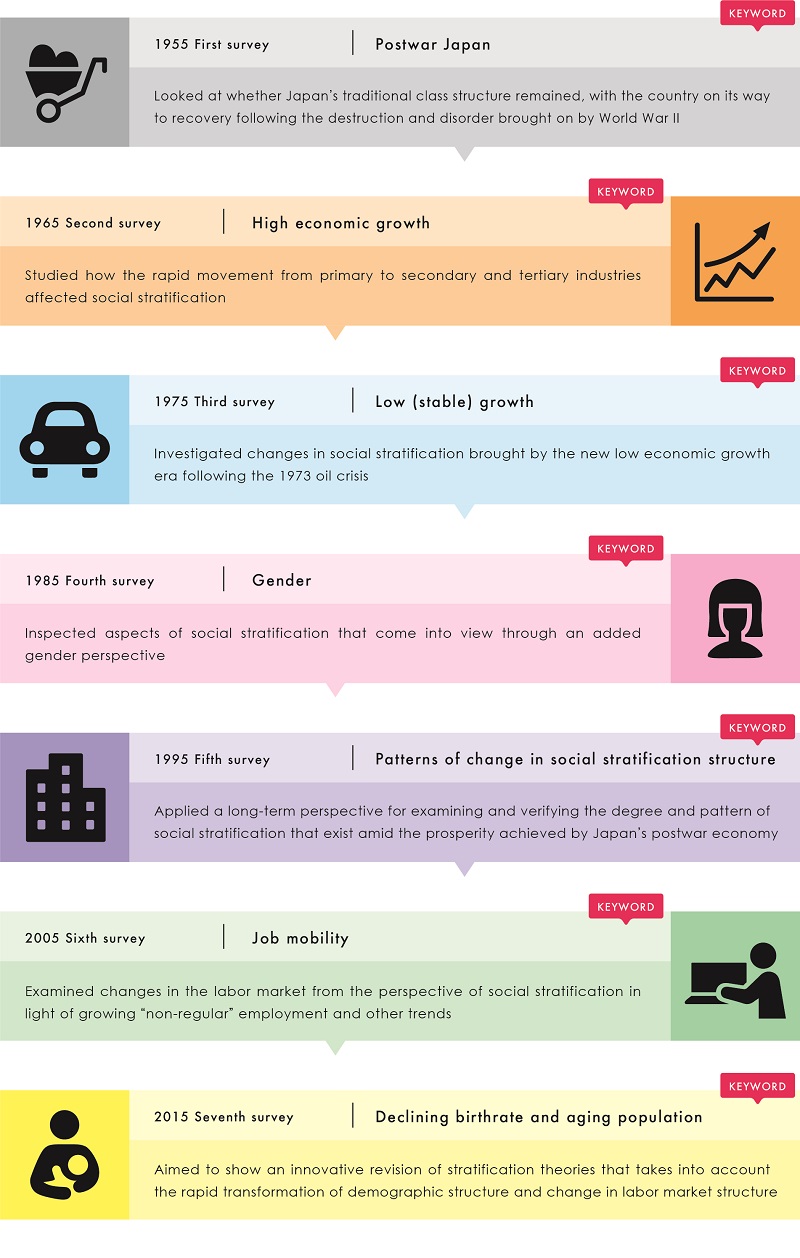

For each decennial survey, a theme signifying the times is chosen to provide a framework for analyzing and discussing the mechanisms behind social inequalities and stratification (figure 4). The main theme for the 2015 survey is Japan's declining birthrate and aging population (shoshi korei-ka). Shirahase, Nakamura, and Arita analyze this data and prepare to present the results to the public according to their specialities—that is, demography and family, education, and the labor market, respectively.

"Taking into account the rapid aging of the population, we bumped up the upper age limit of the survey by 10 years this time, to 79, and added several questions about family, children, and household," explains Shirahase, who is leading the latest project.

Figure 4: History of the SSM survey

Spearheaded by members of the Research Committee on Social Stratification and Social Mobility of the International Sociological Association, the National Survey of Social Stratification and Social Mobility was first carried out in 1955. Researchers were particularly interested in the questions of how advancing industrialization would alter the structure of Japan’s social classes, and how such changes would affect equality and inequality among the people. Since then, scholars with a research interest in social stratification have taken the lead in conducting the survey six more times at 10-year intervals. Both in its history and scale, the SSM survey represents one of the most important scholarly surveys of society undertaken by Japanese sociologists.

Source: SSM survey website: http://www.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/2015SSM-PJ/ssmhistory.html

© 2017 The University of Tokyo.

By poring over the data from the 2015 survey, which they are now analyzing, researchers hope to shed light particularly on the social mechanisms that give rise to an aging society, such as individuals delaying or forgoing marriage altogether; inequalities arising from gaps between regular and "non-regular" employment; and asset retention levels of retired seniors. For example, the survey team has ascertained that where and how people meet their future spouses vary by level of education; and that individuals working as non-regular employees are not only much more likely to remain unmarried, but also have less opportunities for meeting prospective partners. Further, when retired seniors were asked about their social class, their answers were influenced by the level of assets in their nest egg in addition to their income.

Looking ahead, Shirahase says researchers will further analyze the data and look for ways in which their findings can benefit society. They also have a responsibility to pass the data and methodologies amassed through the SSM survey, which they inherited from previous generations of researchers, on to the next.

Shirahase first encountered social stratification theory while studying in the United States. "I was attracted to the clarity with which theoretical arguments could be verified using concrete numbers," she says reminiscently. But behind that clarity is the highly laborious task of sifting through massive amounts of data. And because society is complex, the kind of simple and clear answers everyone would like to have are often elusive. Still, she believes that shining a light on social inequalities and their causes with solid corroborative evidence can help foster programs and policies that improve people's lives. With unwavering faith in the instincts that tell her this is so, she is preparing to pass the SSM survey baton on to the next generation.

Translation: Wayne Lammers

*Top page photo credit: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 jasohill

Researchers (alphabetical order)

Professor Shin Arita

Professor Takayasu Nakamura

Professor Sawako Shirahase