Title

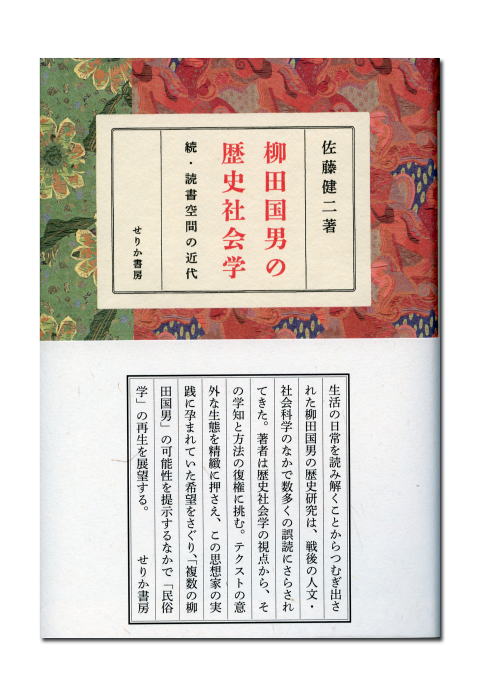

Yanagita Kunio no Rekishi-Shakaigaku (Yanagita Kunio’s Historical Sociology: a Sequel to ‘The Reading Space of Modernity’)

Size

413 pages, 127x188mm, hardcover

Language

Japanese

Released

February 27, 2015

ISBN

978-4-796-70338-3

Published by

Serica Syobo, Inc.

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

This book offers a new perspective on Yanagita Kunio, the renowned founder of Japanese folklore studies, by interpreting his scholarship as historical sociology. In keeping with the sociological approach, it extends its purview beyond his methods of collecting and analyzing folklore materials and data to include the formation of the researching subject, along with the means of publishing and sharing research results, in order to analyze the nature of public forms of knowledge. In this way, the book serves as a sequel to my earlier work, The Reading Space of Modernity: Yanagita Kunio as Method (Kōbundo, 1987).

The idea of exploring Yanagita Kunio’s scholarship as method was deepened by my experience participating in the planning and compilation of a new edition of Yanagita’s complete works (published by Chikuma shobō in 36 volumes), the publication of which began in 1998. Chapter One of Yanagita Kunio’s Historical Sociology discusses the questions of how the wide range of texts left behind by Yanagita should be presented to readers and in what order they should be arranged. These may appear to be straightforward issues to be resolved in the editing of any compilation of material, yet in reality they raise fundamental research questions concerning how we interpret a particular thinker. The principle we chose of ordering the works chronologically according to original date of publication attempted to adhere to the historical timeline of Yanagita’s own textual creation.

Yet in assembling a complete collection of a single author’s work encompassing more than 30 volumes, the totality one must encompass is different than it would be in the case of an editorial project in which each volume stands on its own. How does one portray the entire textual space of the author’s written work, which is also a legacy of the diverse and overlapping areas of his life, ranging from agricultural administration to literature, from the study of folktale transmission to analysis of contemporary society, including social reform proposals based on national language education? What hierarchy should be imposed in representing this vast work? This challenge is not resolved merely by the choice of chronological order. The task immediately raises sociological and media theory questions, including “What is an author?”; “When can we say that a work is complete?”; “What are the criteria for treating a text as published?”; and “What were the meanings invested in headings, indices, and illustrations?” Grappling with these inescapable questions, it became clear how greatly the standard edition of Yanagita’s works, which was completed with the publication of a chronology and index in 1971, had limited the scope of Yanagita studies. The process pointed to the need to make that textual space more fluid, and at the same time offered concrete methods for reconstructing it.

The distinctiveness of this book lies in its treatment of the emergence of folklore studies as a movement in modern Japanese knowledge and its attempt to demonstrate its potential as a form of historical sociology on the basis of concrete textual analysis. The argument concerning the complete works that I lay out in Chapter One, the analysis of aspects of Yanagita’s Tales of Tōno in Chapter Two, the discussion of photography in Chapter Three, and the re-examination of the history of folklore studies in the final chapter all pursue this same effort. Chapters Four and Five review and put to rest the nation-state critiques and portrayals of Yanagita Kunio as an intellectual trapped within colonialist ideology that created such a furor in the 1990s. Not only were these critiques mistaken in their analysis of the texts, but they lacked the resolve to conceptualize a new construction of Yanagita’s work.

In this sense, Yanagita Kunio’s Historical Sociology is both an idiosyncratic guide to a new textual space and, at the same time, an introductory work seeking to establish the unfamiliar field of historical sociology.

(Written by SATO Kenji, Professor, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology / 2017)

Find a book

Find a book