Title

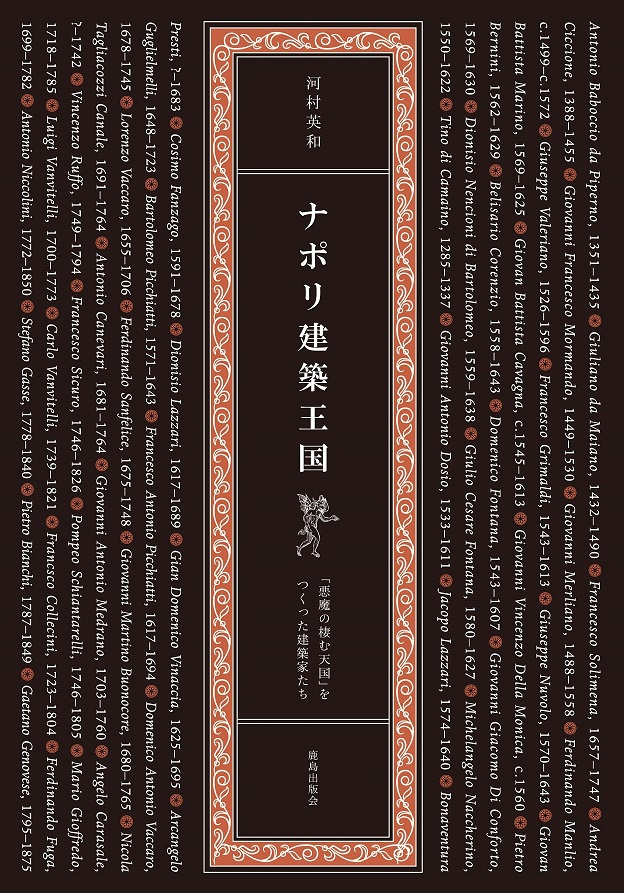

Napoli kenchiku okoku : Akuma no sumu tengoku o tsukutta kenchikukatachi (History of Neapolitan Architecture)

Size

256 pages, A5 format, hardcover

Language

Japanese

Released

October 08, 2015

ISBN

978-4-306-04628-3

Published by

Kashima Institute Publishing Co., Ltd.

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

This volume focuses on the history of Naples, the largest city in southern Italy and its unique local architecture between the 16th century and the early 20th century. The subtitle of the book is the well-known Italian saying, “paradiso abitato da diavoli (paradise inhabited by devils)”, which describes the ironic metaphor of the city of Naples. This phrase is derived from one of the old proverbs of the 17th century that became better known when it became the title of a book by the Neapolitan philosopher, Benedetto Croce. The heavenly enchantment of the splendid view of the Gulf of Naples with Vesuvius in the background has led to the well-known saying, “Vedi Napoli e poi muori (See Naples, then die)". On the other hand, there were lazy people called ‘lazzarone’ everywhere in Naples: one of the lowest class people who do not work, similar to beggars. Moreover, Neapolitans themselves made the city with filthy and insanitary alleys, where sometimes cholera spreads. These Neapolitans were compared to “devils.” In fact, the Neapolitan paradise depended not only on the benefits of the climatic and natural beauty but also on the individual buildings of the city.

The period of greatest splendor in the history of Neapolitan architecture would be the Baroque period from the second half of the 16th century to the 18th century, which corresponded to the period of the Kingdom of Naples and the Two Sicilies. Before the Renaissance, many Tuscans, or North Italian architects had already taken the initiative of developing the architectural works of this city. For example, one of the leading architects Cosimo Fanzago was Lombardian. He was talented in multicolor marble inlay works for walls, floors and altar decorations, as well as in doing fascinating sculptural works motived by fruits and angels. Later in the rococo period, Neapolitan architects such as Ferdinand Sanfelice and Domenico Antonio Vaccaro rather preferred to work for important architecture in Naples. For example, a temporary structure used for religious and royal festivals, called 'macchina da festa', was made using marble for eternal use, which is called ‘guglia (spires or columns)’. Moreover, 'fountains (fontana)' were made in towns and squares as ‘urban decoration (arredo urbano)’. Certainly, this baroque theatricality also arrived in private residences. The portals of the Neapolitan noble palaces were sumptuously and highly decorated up to two or three floors and in their courts settled the unique staircase space named 'scala aperta (opened staircases)' similar to certain Italian opera scenography. From the second half of the 18th century began neoclassicism, its architecture was also based in Naples and on the rule of "noble simplicity and quiet grandeur" so called by Winckelmann, which was led by two great papal architects: Luigi Vanvitelli and Ferdinand Fuga. In any case, the most important material of the Neapolitan architecture had always been two types of volcanic stone: dark gray igneous rock (piperno) and yellow tuff (tufo giallo). These bright and dark colors bring the effect of contrast between light and shadows, similar to the city of Naples which fascinatingly contains both paradise and hell.

(Written by Ewa Kawamura, Specially Appointed Associate Professor, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology / 2017)

Find a book

Find a book