Title

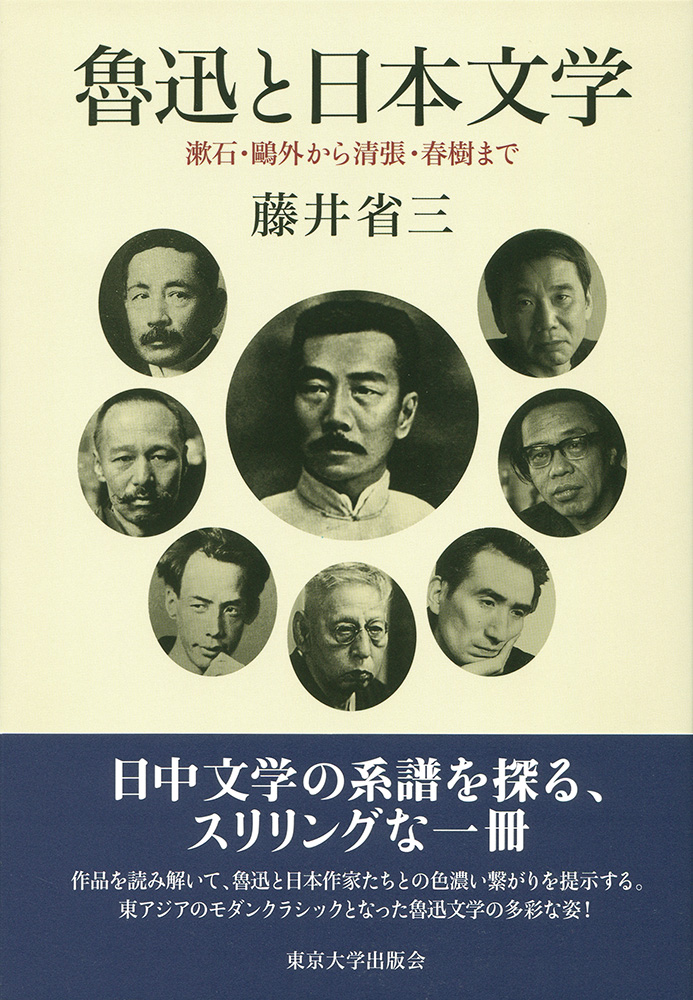

Rojin to Nihon bungaku (Lu Xun and Japanese literature: From Natsume Sōseki and Mori Ōgai to Matsumoto Seichō and Murakami Haruki)

Size

280 pages, 127x188mm

Language

Japanese

Released

August 18, 2015

ISBN

978-4-13-083066-9

Published by

University of Tokyo Press

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

Lu Xun (1881–1936), the father of modern Chinese literature, continues to have an enormous influence on China even today, and one cannot discuss contemporary China without mentioning Lu Xun.

As well, for the past hundred years Lu Xun has attracted the attention of cultural circles in Japan, and his complete works have now been published in Japanese translation. Some of his works are included in all middle school textbooks for the Japanese language, and collections of his writings are available in various paperback editions. The Japanese have accepted Lu Xun almost as if he were a national author.

Lu Xun’s works have also been eagerly read by generations of readers in Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Southeast Asia. Lu Xun is part of the cultural heritage shared by East Asia, and his works could be described as modern classics.

From 1902 to 1909 Lu Xun studied in Japan, where he came under the influence of authors such as Natsume Sōseki and Mori Ōgai, and when he began writing in earnest in Beijing in 1918, he also paid close attention to other Japanese writers such as Akutagawa Ryūnosuke and Satō Haruo.

In chapter 1 of this book I consider Sōseki’s influence on Lu Xun. For example, a shadow of loneliness follows the protagonist of Sōseki’s Botchan, and Lu Xun developed the image of this character to write “The Real Story of Ah-Q” (1922), a masterful critique of the national character of the Chinese. Botchan, the lonesome narrator of Sōseki’s novel, has no family name, and “Botchan” is not even his nickname, being no more than the narrator’s self-designation. In this respect, he is genealogically related to the similarly nameless Ah-Q of Lu Xun’s story.

In chapter 2, I discuss the process whereby, through his reception of Ōgai’s “The Dancing Girl,” Lu Xun produced “In Memoriam,” a story of tragic love. In chapters 3 and 4, I discuss the influence of Akutagawa’s short stories on those of Lu Xun, and I also compare the reception of the legend of the Wandering Jew by both authors.

In this fashion, up until the 1920s Lu Xun was learning from Japanese writers, but in the 1930s he conversely began to have an influence on them. An important role in this period of transition was played by Satō Haruo, who is taken up in chapter 5. In the 1920s Lu Xun had been studying Satō’s writings, but in the 1930s Satō greatly facilitated the acceptance of Lu Xun in Japan by, for example, translating a selection of his writings for the Iwanami Library series.

This reception of Lu Xun in Japan first bore fruit in a major way in Dazai Osamu’s biographical novel about Lu Xun called A Sorrowful Parting (1945). But owing to the biased views of Takeuchi Yoshimi, who debuted during World War II with a highly opinionated book about Lu Xun, Dazai’s view of Lu Xun was gradually sidelined, a process that is discussed in chapter 6.

Meanwhile, a writer who, although a contemporary of Dazai, reacted unfavourably to the image of Lu Xun as a member of the elite land-owning class was Matsumoto Seichō, taken up in chapter 7. In 1955, Matsumoto published the anti-Lu Xun “I” novel “The Patrilineal Finger,” whereafter he became a writer of crime fiction.

Murakami Haruki, the subject of chapter 8, has been an avid reader of Lu Xun since his high school days, and since his debut as a writer he has put forward some penetrating ideas about Ah-Q. In his novel 1Q84, Murakami situates Ushikawa, the third main character, in the same lineage of characters as Ah-Q on account of his namelessness and other characteristics.

In the above eight chapters, this book presents in the context of Japanese and Chinese literature a lineage of images of Ah-Q leading from Sōseki to Lu Xun and then to Murakami, a lineage about “home” leading from Lu Xun to Matsumoto, and the strong influences to be found operating between Ōgai, Akutagawa, Satō, and Dazai on the one hand and Lu Xun on the other. I hope that this kaleidoscopic picture of Lu Xun will be able to serve as a way of unravelling the complex and ever-changing relations between Japan and China during the past hundred-odd years.

(Written by FUJII Shōzō, Professor, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology / 2017)

Find a book

Find a book