Title

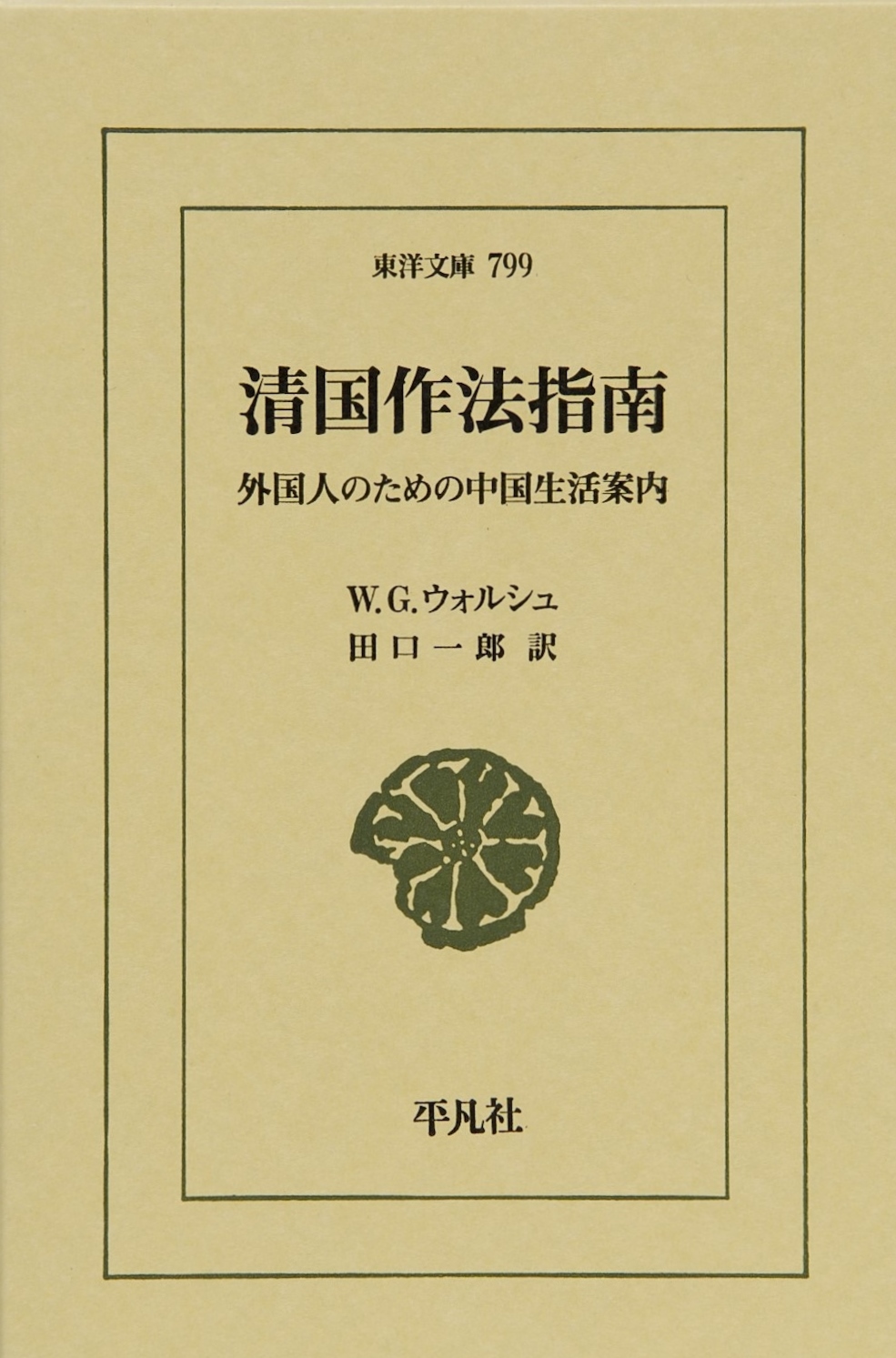

[Toyo Bunko 799] Shinkoku Saho Shinan (Ways that are Dark – Some Chapters on Chinese Etiquette and Social Procedure)

Size

322 pages

Language

Japanese

Released

September 11, 2010

ISBN

978-4-58-280799-8

Published by

Heibonsha

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

Would it be possible for modern Japanese people to live in China of the late Qing Dynasty? If we were to do so, we might face many difficulties because, among other things, we would not know how to greet people, where to sit at a banquet, how to deal with a burglary, the right size of visiting cards, how to behave at a wedding feast, or how to act when we are asked for a donation. Even modern-day Chinese people might find themselves at a loss in these situations. However, such knowledge is sometimes required when studying literature, or history, among other subjects. This book provides answers to the above questions by referring to a record of manners and customs of the late Qing Dynasty, which were noted by Walshe, an English priest that visited China at the end of the 19th century. “Customs” are ordinary practices of people living in a given local community, which is considered common sense. Therefore, it is difficult to keep systematic records of customs. Only people that cannot learn them in their daily life or those that need to explain them to the outside world would need to record them. The well-known documents, such as “Shinzoku kibun,” compiled by Tadateru Nakagawa, the magistrate of Nagasaki, and “Pekin fuzoku zufu,” written by Masaru Aoki, were edited by Japanese people. “The Adventure of Wu,” written in English by H. Y. Lowe (translated into Japanese by Shozo Fujii et al. as “Pekin Fuzoku Taizen”) was written for foreigners. This book also has a similar perspective.

Another characteristic of this book is that it has been written from the viewpoint of a participant instead of that of an observer. For example, the books mentioned above describe how Chinese brides and grooms behave at weddings. However, this book was written from the perspective of people that were invited to the wedding. In Chapter 14, “Wedding Feast,” concrete instructions are given; including the time and the type of invitation cards that should be sent, the type of presents that should be given, and the words that should be spoken at wedding feasts, or in other words, “what people should do.” Secondly, the content of this book is very practical. “Shinzoku kibun” and other books explain manners and customs that are different from Japan in detail. However, trivial matters of life that are not elegant, such as funerals, thieves, fires, land transactions, and the manners to observe when visiting a sick person, among others have hardly been mentioned in these books. In contrast, this book minutely explains all these topics. Walshe did his missionary duties through interacting with local people. He was not motivated by an interest in a “different culture” and did not intend to introduce the Chinese culture to the outside world. As a result, he kept different types of records. Thirdly, photographs are used in this book. It is difficult to understand how to do “Zuo Yi (making a bow with hands folded in front)” by reading “Pekin fuzoku zufu.” On the other hand, this book shows sequences of photographs that make it clear. Moreover, people had to take off their glasses upon meeting a higher-ranking person on the street. This book shows how glasses had to be held at such times by using a picture.

I sometimes demonstrated my knowledge obtained through this book to Chinese people, which surprised them. They asked me, “why do you know such things?” The Qing Dynasty has become a thing of the past. However, the manners of the old days might be preserved in foreign countries.

(Written by Ichiro Taguchi, Associate Professor, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences / 2017)

Find a book

Find a book