Title

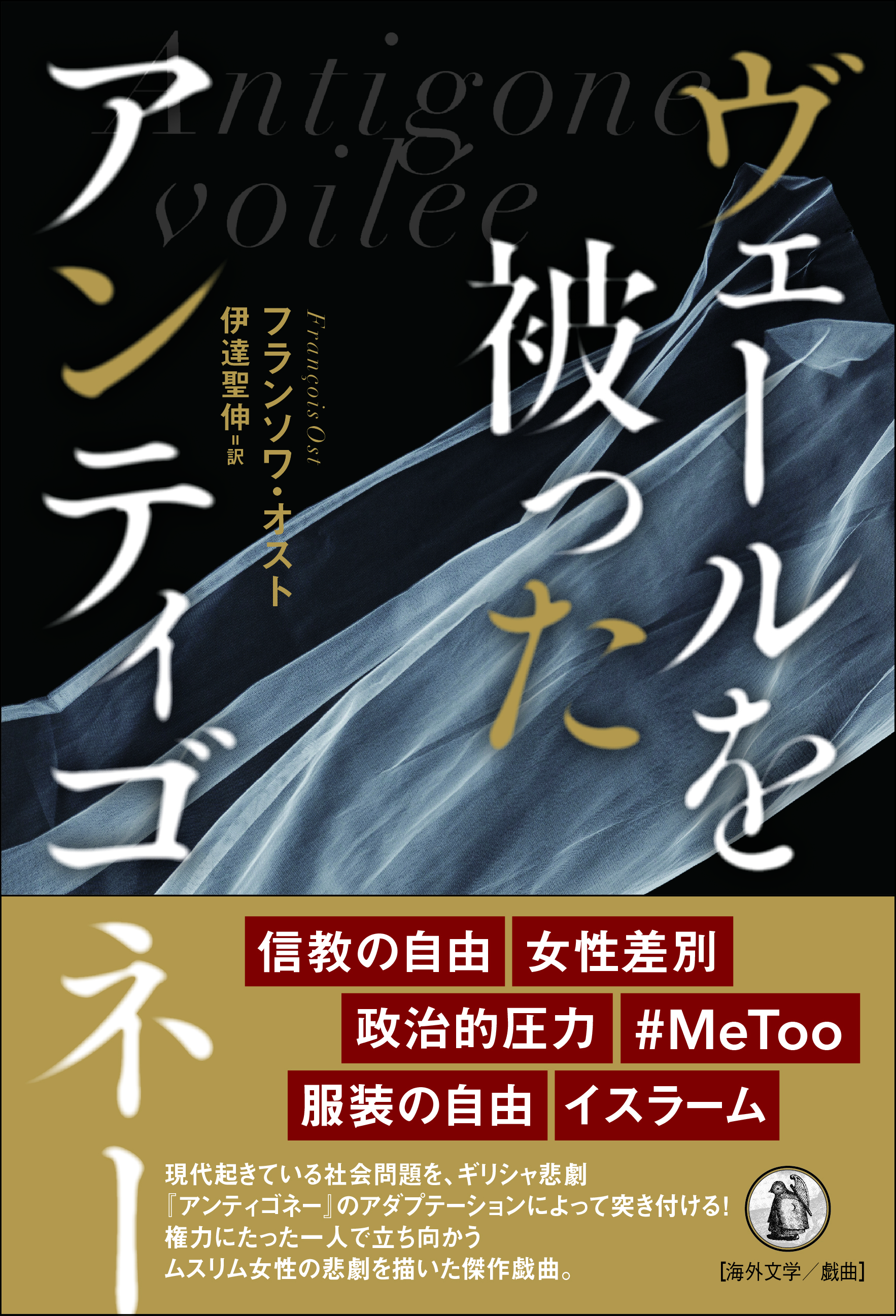

Veil o kabutta Antigone (Antigone Wearing the Veil)

Size

192 pages, 127x188mm

Language

Japanese

Released

August 10, 2019

ISBN

9784909812179

Published by

TAKANASHI SHOBOU

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

Sophocles’ Antigone is a celebrated masterpiece of Ancient Greek drama, in which Antigone, who has lost her beloved older brother, Polynices, defies a prohibition by King Creon, her uncle, and buries her brother. As literary critic George Steiner has discussed, the five eternal human conflicts are condensed in this work: man versus woman, old versus young, society versus the individual, the living versus the dead, and the human versus the divine. Sophocles’ text has also prompted philosophical meditations by Hegel, Derrida, and Butler, among others, and inspired adaptations by dramatists such as Cocteau, Anouilh, and Brecht.

This book is a Japanese translation of Belgian legal philosopher François Ost’s adaptation of Antigone. It is set in contemporary Europe, and the part that overlaps with Antigone is a Muslim girl named Aïcha, who is in secondary school. In Ost’s adaptation, Nordan (Polynices), Aïcha’s dead older brother is suspected to be a terrorist, and her school principal forbids students from attending his funeral, so she protests by wearing the veil.

This play was inspired by the French law of 2004, which prohibits the wearing of the veil in public schools in the name of laïcité (separation of church and state). What should be done to uphold religious neutrality in public schools in a secular society while also guaranteeing students’ freedom of religion? While this issue is prone to developing into ideological disputes, Ost’s adaptation uses the power of literature to draw us into specific situations and scenarios and to reflect on them.

It is not common for a legal philosopher to write a play. However, Ost, who teaches a Law and Literature course at a university in Belgium, emphasizes the effectiveness of literature in an interview included in this book. He says that imagination is indispensable for a legal professional’s work, but he also warns that today’s legal professionals are liable to fall into a rut of short-sighted specialization. Unlike the study of law, in which students “learn the answers that have already been prepared,” literature is, as Paul Ricœur has said, “a laboratory of human experience (un laboratoire expérimental de l’humain).” He then goes on to say that the pursuit of “the meaning of the possible” that one obtains from works of literature is “very much needed in today’s university education.”

As I was translating this book while on sabbatical from research in Canada in 2017, I became deeply impressed by how timely it was. It was the year that the province of Québec enacted a law stipulating that both parties must show their faces to each other in the exchange of public service (essentially a law regulating the use of the Islamic niqab or burqa), and it was also the year that the #MeToo movement swept across the world. There must certainly be many who follow in the footsteps of Antigone and Aïcha (especially women). The editor in charge of this book told me that the book “also raises several issues that really seem as if they are written for contemporary Japan,” and I would happy as a translator if the reader could also discover that within the pages of this book.

(Written by DATE Kiyonobu, Associate Professor, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences / 2020)

Find a book

Find a book