Title

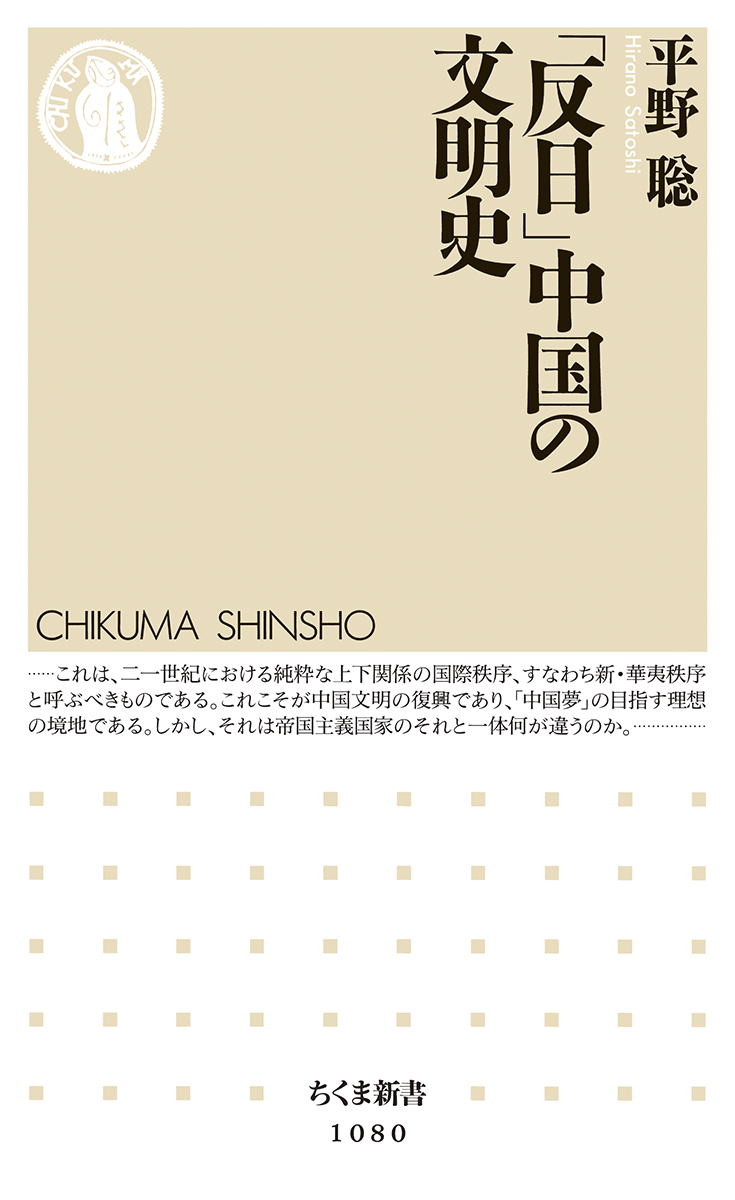

Chikuma Shinsho “Hannichi” Chūgoku no bunmeishi (The history of “anti-Japanese” China’s civilization)

Size

272 pages, paperback pocket edition

Language

Japanese

Released

July 10, 2014

ISBN

978-4-480-06784-5

Published by

Chikumashobo

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

During a long history, Japan and China are said to have built up a close relationship through their sharing of the Chinese writing system and Confucianism and through the exchange of products of their respective cultures. But what has been the reality of their relationship? It is true that in premodern times there was exchange between the two countries, symbolized by Japan’s embassies to Tang China and the arrival of the Chinese monk Jianzhen (Ganjin) in Japan, but periods during which interpersonal contacts ceased and only a small amount of trade continued were far longer. This was mainly because Chinese civilization was an inland agrarian civilization unused to the sea, while Japan, in spite of its demands for Chinese cultural institutions and goods as the need arose, did its best to avoid political subservience and friction with the help of the intervening sea. But confrontations between China and Japan did sometimes occur, and these were generally accompanied by force of arms, as a result of which the two countries have espoused unfavourable images of each other, Japan’s image of China being coloured by the Mongol invasions of the late thirteenth century and Chinese civilization’s image of Japan being coloured by the so-called Japanese pirates and Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s invasions of Korea in the late sixteenth century. Later, in the Edo period, Japan adopted Confucianism and developed its own view of Japan and China, while Chinese civilization, under the rule of the Qing dynasty, a state centered on horse-riding peoples, had almost no interest in Japan, lying as it did beyond the sea.

The roots of today’s friction between China and Japan lie in the fact that in the context of modern international relations they have had to engage directly with each other. In the case of Japan, it acted somewhat rashly on the idea of “Asianism” as a way to counter Euro-American hegemony together with other countries in Asia, thinking that Japan itself, which was part of the same Sinographic civilization, could become the new leader of Asia, and it was only natural that this should have provoked an angry response from the people of modern China, who had inherited the self-awareness that theirs was the most advanced civilization. Meanwhile, modern China, which had fallen behind Japan in its receptiveness to the modern West, experienced a refreshing shock at the growth of Japan during the Meiji era and actively adopted terms newly coined in Japan as it pressed forward in building “another modern Japan.” But at the same time, while it was being swallowed up by the dog-eat-dog worldview of rivalry between the great powers, modern China reinforced the notion that it would exercise the sense of morality of a great power and truly save smaller countries. This became the reason that China fought with the Soviet Union over the position of the center of socialism and struggled with poor growth, and it is also linked to its antagonism towards other major countries in spite of professing its recent emergence as a superpower to be “peaceful.”

Thus, present-day China harbours feelings towards Japan, of which it has always had to be conscious when shaping its own nationalism, that are all the more complex because it has lived through a history during which it has not necessarily been able to gain its own rightful position in international society. On the one hand, this has tied in with an interest in learning more about Japan and has led to an upsurge in visits to Japan and in Japanophiles. But on the other hand it has also caused backlashes against people excessively close to Japan and a strong desire to make it known that it is China, not Japan, that represents Asia. By combining with various internal contradictions, these conflicting emotions have given rise to the Communist government’s harsh diplomatic stance towards Japan.

This book begins by delineating the above historical currents from the viewpoint of Chinese civilization and from the vantage point of several millennia of chaotic history, and by tracing the mode of consciousness that links this history to the present day, I endeavour to enable the reader to gain a multifaceted understanding of a China that is not simply “anti-Japanese.”

(Written by HIRANO Satoshi, Professor, Graduate Schools for Law and Politics / 2018)

Find a book

Find a book