Title

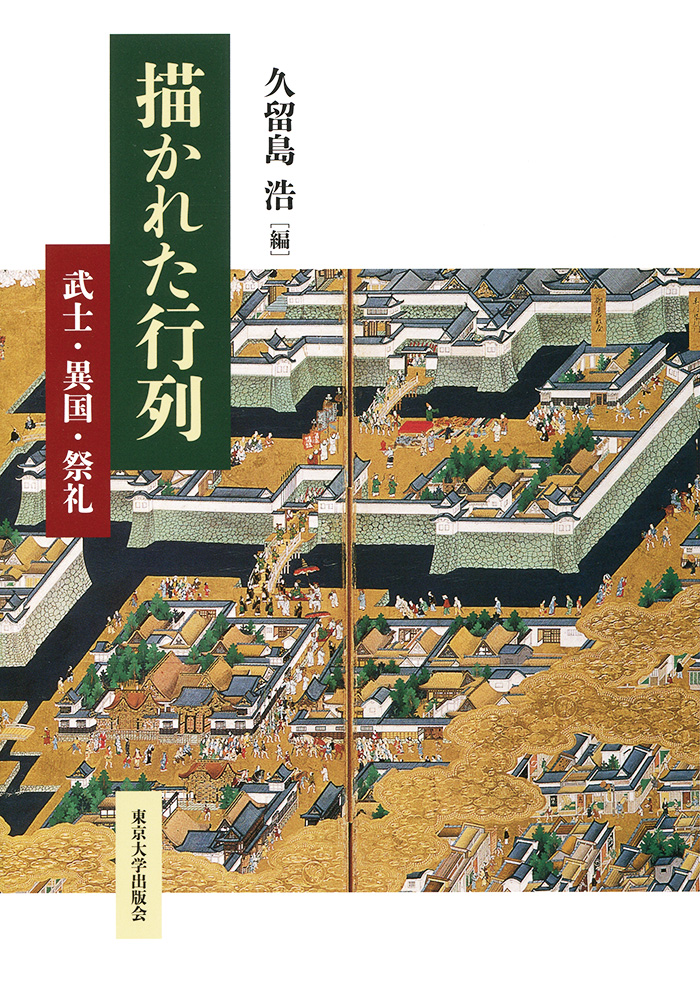

Egakareta Gyoretsu (Depictions of Processions: Samurai, foreign embassies, and festivals)

Size

392 pages, A5 format

Language

Japanese

Released

October 23, 2015

ISBN

978-4-13-020154-4

Published by

University of Tokyo Press

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

A collection of essays edited by the director-general of the National Museum of Japanese History, Hiroshi Kurushima, this volume comprises 13 studies that examine images of processions in the region, focusing on early modern Japan, but also including China and Korea as well. As the editor notes in his introduction, the basis for this book was an exhibit held at the National Museum of Japanese History, “Early Modern Japan through Its Parades: Samurai, Foreign Embassies, and Festivals” (October 16–December 9, 2012). The exhibit looked at early modern Japan as an era of parades, and having gathered together images of processions held during that period, it broadly divided them for display into the categories of (1) processions of samurai, (2) processions of delegations from foreign countries, and (3) festival processions. In other words, it was an attempt to think about early modern Japanese society through the depictions of these parades. This book builds on the issues as delineated in the exhibit, and in addition to discussions based on the three perspectives noted above, incorporates discussions of Chinese and Korean processional images as well, with the intention of offering a comparative viewpoint.

The goal of this volume is above all to elucidate early modern Japanese society through these depictions of processions. Accordingly, most of the authors included in this volume are scholars of early modern Japanese history. By contrast, I specialize in Korean medieval and early modern history, and I thus contributed an essay on depictions of Korean processions from about the same time period as Japan’s early modern era in order to offer the comparative perspective noted above. I will briefly introduce the contents of my chapter here.

I focused primarily on images called banchado, or documentary paintings. Among the public records compiled by the state during the Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), there are books called uigwe (records of state rites), a type of report that records all of the details on important state affairs, such as the rites and large-scale undertakings carried out by the king or the royal family. In the banchado that were recorded as attachments to uigwe, the king’s procession for each type of event is depicted in detail. However, these illustrations were not intended to be appreciated as art, but rather to serve as maps to be checked beforehand by all participants and relevant people so that on the day of the event, these grand processions of more than 1,000 people could be smoothly organized. For that reason, the renderings of humans, horses, and so on are uniform and monotonous yet detailed, and they are characterized by the fact that when drawing the procession, there are three set perspectives—left, right, and from the back—and depending on the person or animal’s position in the procession, they are shown standing and facing different directions.

However, among the numerous banchado created as uigwe attachments, the banchado included in the Wonhaeng Eulmyo jeongni uigwe (The royal protocol on King Jeongjo’s visit to his father’s tomb in the year of Eulmyo) stands out as being drawn in a completely different manner. This banchado depicts the procession during the royal visit by King Jeongjo (r. 1776–1800) in 1795, but the people and horses are portrayed with diverse expressions and engaged in various actions, and the entire procession is drawn in the same direction as the map (i.e., the procession is seen from one set vantage point). In other words, in contrast with other banchado, there is a strong pictorial element to it. Why was this banchado alone drawn in this style? I presented my hypothesis in this chapter that, keeping in mind the political significance of King Jeongjo’s royal visit, this particular banchado was designed so that in addition to playing the usual role as a map, it could also be appreciated as a visual record of the grandeur of the procession that could be passed on to future generations. While the veracity of that hypothesis will require further research, I believe that it is a significant chapter in that it offers a detailed introduction for Japanese readers to a depiction of a premodern Korean procession that had previously been little known.

I would like to note that, in addition to the chapter written by myself, the volume includes four additional chapters contributed by University of Tokyo faculty members (chapters 7, 11, 12, and 13).

(Written by ROKUTANDA Yutaka, Professor, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology / 2017)

Find a book

Find a book