Title

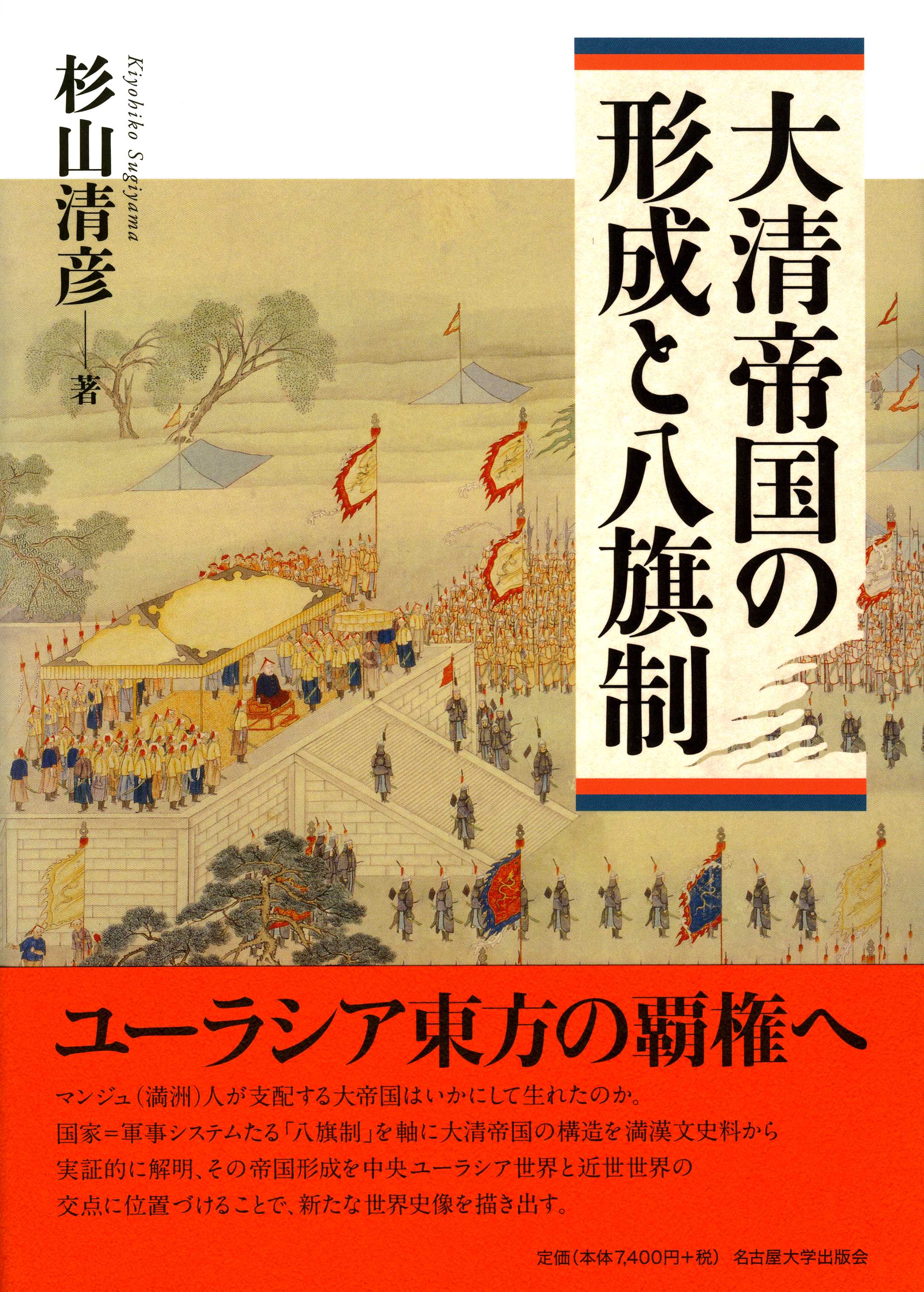

Daishin Teikoku no Keisei to Hakki sei (The Formation of the Qing Empire and the Eight Banner System)

Size

574 pages, A5 format, hardcover

Language

Japanese

Released

February 28, 2015

ISBN

978-4-8158-0798-6

Published by

The University of Nagoya Press

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

What would readers imagine from the term “Qing dynasty”? Some may think of the prospering Chinese Empire from the Kanxi to Qianlong emperors, and others may be drawn to the fall of the Chinese Empire triggered by the Opium war. Yet others may think of the last dynasty of the Imperial China which had been perpetuated for millennia since the Qin dynasty.

However, these are all nothing but the images of Chinese dynasties, where the central notions are of intellectuals and bureaucrats who wrote in Chinese characters and followed Confucianism. Nevertheless, the founders of this dynasty were not Han-Chinese, but the people of Jurchen, who called themselves Manchus. Manchu written in Chinese [満洲] uses these letters only as phonograms, to represent the sound “manju,” which refers both to the ethnic group and their empire (hence Manchu is not originally a name for the locality). The Manchus spoke the Manchu language, of the Tungusic family, and used Manchu characters, derived from the Mongolian script, rather than speaking and writing in the Han (Chinese) language.

I study these people based mainly on records and archives in the Manchu language, looking into how they founded their nation and developed into a powerful empire in the 17th century. The nation was called daicing in Manchu, and written in Chinese as da qing [大清]. Considering these, this book approaches the Qing dynasty not as one of the series of Chinese dynasties, but as an empire with the title of daicing, that is, the Daicing gurun in Manchu, or the Qing Empire, with the intention to contextualize it on the same plane as those of the Mongol or Ottoman Empires.

The founding father Nurhaci established a military system called the Eight Banners, which was the central mechanism to form and administer the empire that followed. The Eight Banners was a military organization, and also a social and hierarchical community for the Manchus, comprising the ruling classes and common people throughout the Qing era. As a system, the Eight Banners was clearly defined, but at the same time, it was operated internally based on superior-vassal and/or matrimonial relationships. Through this dual-system formation, it embodied both the military function and individual-dependent gravity for group cohesion.

From another perspective, the Eight Banners was not a system unique to the Manchus. It derived from a type of military-political system typical of Central Eurasia, as a variant that was the most centralized and concentrated. Taking these points into account, I suggested that the true and original image of this nation was not the Qing dynasty of China, but the Qing Empire of Central Eurasia.

From “the Qing, the last dynasty of the Imperial China” to “an empire of Central Eurasia, descendant of the Mongol Empire”—changing the perspective like this not only necessitates a review of this dynasty itself, but also inspires various perspectives on the early modern period and the modern age. Meanwhile, considering that the vast territory of modern China was originally the land which the Manchu regimes cultivated by virtue of the Eight Banners, various internal problems in China today appear to be deeply rooted in the fact that the country inherited only the model of the system by force. Through the attempts made in this book, readers will hopefully appreciate the interest of scrutinizing history and the great range of historical reviews.

(Written by SUGIYAMA Kiyohiko, Associate Professor, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences / 2017)

Find a book

Find a book