Title

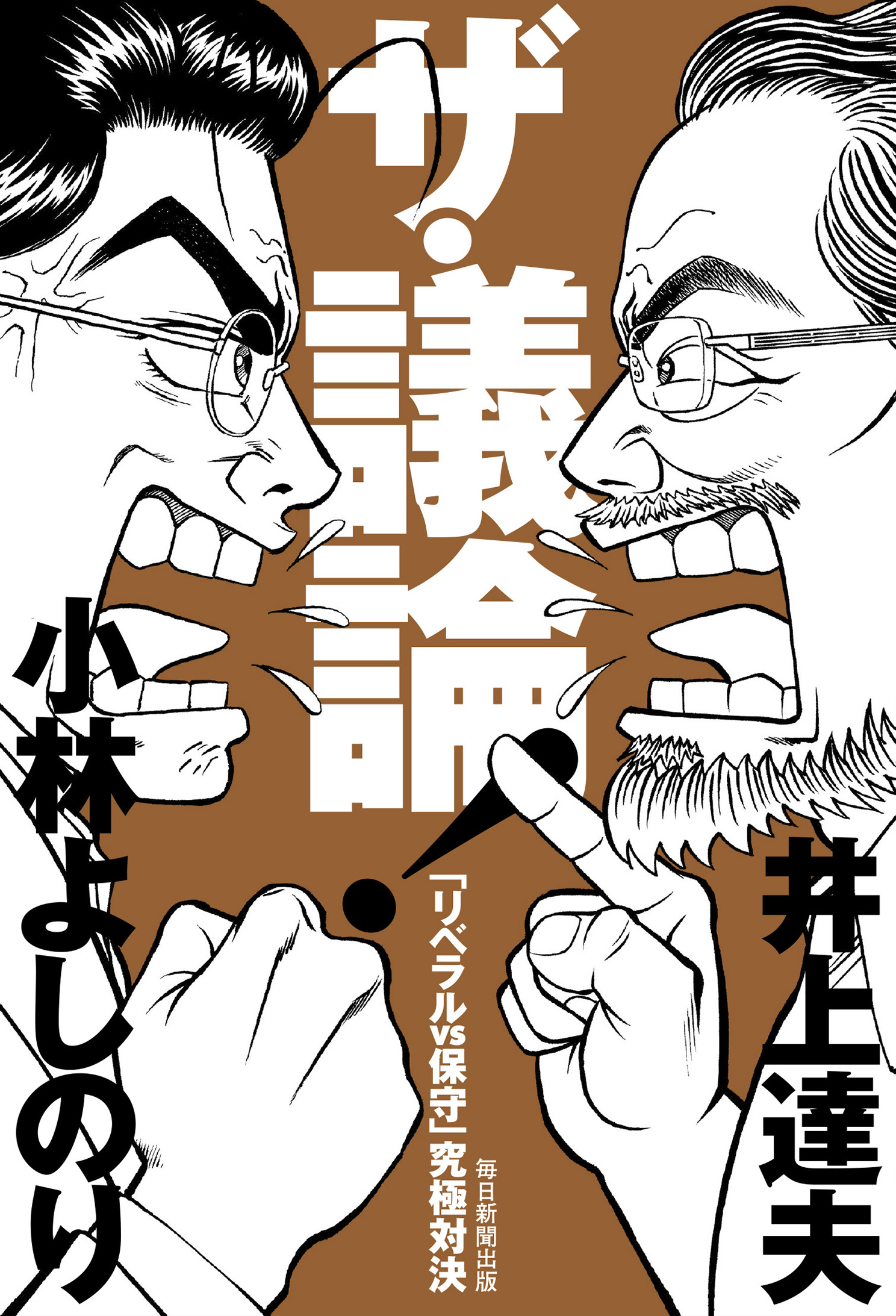

The Giron! (The Debate : Liberals vs Conservatives - The Ultimate Showdown)

Size

256 pages, 127x188mm

Language

Japanese

Released

November 11, 2016

ISBN

978-4-620-32421-0

Published by

Mainichi Shimbun Publishing Inc.

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

Post-war Japanese politics was once characterized by the opposing axes of Hoshu (conservatives) versus Kakushin (reformists), but with the end of the Cold War, because of the self-destruction of Communism and Socialism, the term “Kakushin,” as merged with a socialistic intent, fell out of use. As a result, from around the turn of the century, the position opposing the conservatives, who have controlled successive Liberal Democratic Party administrations, is now called “liberals,” and in place of Hoshu versus Kakushin, we now have Hoshu versus liberals. However, in an ideological meaning transcending party politics, it is unclear what liberals and conservatives are and where their fundamental antipathy lies. Such ideological ambiguity also gives rise to confusion in the opposing images of the parties.

Mr. Yoshinori Kobayashi, the self-proclaimed “true conservative,” who pioneered the “ideological manga” genre and the author, Tatsuo Inoue, who has worked to philosophically restructure liberalism with the principle of justice as his standard and criticized the deceit of Kakushin who now disguise themselves as liberals, debate the three great themes of post-war Japan. These are the relationship between the Emperor System and democracy, war responsibility and historical perception, and Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution and the poverty of post-war thought. This is done in an attempt to bring light to the conservative and liberal ideological core and the points of opposition and commonality between the two camps.

While self-styled conservatives and right wingers in Japan disregard the intent of the present Emperor in opposing revision to the Imperial Household Law and support the Abe administration, which is strengthening Japan’s position following the U.S. line, Kobayashi sharply criticizes these people, calling them “traitors” and “boneheaded conservatives.” While self-proclaimed liberals take up the banner of upholding the Constitution, the author harshly denounces them as political opportunist fake liberals, who distort the Constitution to trample upon constitutional democracy. Both the author and his interlocutor share the desire for a deeper philosophical introspection through sincere dialogue with the other side, based on their criticism of the current state of affairs in Japan, where the battle lines have been drawn between partisan groups and activists on the left and right shouting into their own echo chambers and by freely and independently confronting the issues of modern Japanese society from their respective positions. While most could not have foreseen this dialogue between Yoshinori Kobayashi and Tatsuo Inoue, considering the commitment to intellectual independence and integrity that the two share, it was a natural turn of events.

Concerning the three great themes that were discussed, both agree in their criticism of the deceit of the alleged Gokennha (Constitution-protectionists) in the Article 9 question and denunciation of the Abe administration’s increasingly subservient stance toward the U.S. as an abandonment of Japan’s political autonomy, and in their stout defense of the freedom of thought and speech that is critical of power. The author and Mr. Kobayashi are opposed in their positions on the Emperor system, respectively advocating abolition and continuation of the system. They also hold opposing views, when it comes to the question of war responsibility, with Kobayashi seeking to deny and limit Japan’s blame by focusing on the intent of Japanese Asia-centrism to liberate the region from Western imperial oppression, and Inoue claiming that Japan must come to a frank recognition of this responsibility (including the wartime responsibility of the Showa Emperor) precisely in order to have the moral ground to hold the West accountable for the same issue. However, commonalities lie beneath even these polarized viewpoints. Kobayashi defends the Emperor system, claiming that it is necessary to keep democracy from becoming a tyranny of the masses, a concern which the author shares. The difference is that the former seeks this check on such majoritarian tyranny of the mass democracy through the Emperor, while the latter finds it in the constitutional guarantee of human rights. Both men are also of the same opinion in criticizing the current situation where the Emperor and the Imperial Household are deprived of their own human rights, and share a critical view of Western deceptiveness in turning a blind eye to their own wartime culpability.

Kobayashi supporters, among the readers of this book, shared impressions like “I realized that among Japanese liberals whom I thought hypocritical there is an upright thinker like Tatsuo Inoue,” while some liberal readers commented “I thought Yoshinori Kobayashi was a right-winger, but, in some ways, he’s more liberal than I imagined.” It appears that the aim of this book, which is to deepen mutual understanding between liberals and conservations through two authors with differing positions engaging in sincere dialogue, has met some success. It is also to be noted that the author’s long advocated theory concerning Article 9, which is to delete it and incorporate norms that control war potential into the Constitution, is further developed and presented in a detailed and concrete form of an actual revised Constitution draft.

(Written by INOUE Tatsuo, Professor, Graduate Schools for Law and Politics / 2018)

Find a book

Find a book