Title

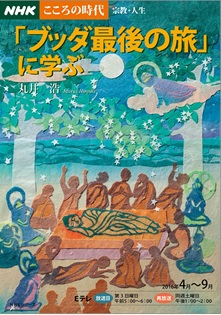

“Buddha Saigo no Tabi” ni Manabu (Learning from “The Last Journey of the Buddha,” the guide book for an NHK E-tele program series entitled “The age of kokoro: religions and life,”)

Size

180 pages, A5 format

Language

Japanese

Released

March 25, 2016

ISBN

978-4-14-910931-2

Published by

NHK Publishing

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

According to scriptural texts of Early Buddhism, Gotama Buddha started on his last journey from Rājagaha, crossed the Ganges, made a rainy-season-stay on the suburbs of Vesālī, fell seriously ill there, and announced that he would die after three months; then he went further up north to the city of Pāvā, underwent a fatal food poisoning with a meal served by one of his lay followers, and finally entered nirvana between a pair of Sāla trees at the age of eighty in Kusinārā. The most detailed account of Buddha’s last journey is found in the Mahā-parinibbāna-suttanta (=MPS) belonging to the Sutta Piṭaka of the Pali Canon, the standard collection of scriptures of Theravada Buddhism in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia.

The MPS was translated into Japanese by two distinguished scholars of Buddhism, the late Dr. Hajime Nakamura and the late Dr. Shoko Watanabe. Dr. Nakamura’s translation is full of instructive notes and Dr. Watanabe’s translation is accompanied with useful explanations. There are some more translations or explanatory books written by other Japanese scholars or writers. Accordingly, the MPS is one of the most well-known sutras of Early Buddhism in Japan. Nevertheless, there seem to remain many unsolved riddles concerning this work. Moreover, as a masterpiece of the religious literature that thematized the death of Buddha, it is always our option to seek for a new meaning and interpretation.

The present book is a small attempt to pursue a new meaning of “the last journey of Buddha” in the MPS from the author’s original viewpoint as a scholar of Hindu systems of philosophy, depending on Nakamura’s and Watanabe’s Japanese translation and explanation. Ultimately, this work is intended to reconsider the significance of Dr. Nakamura’s lifelong pursuit for the idea of “Buddha as a human” in connection with the contemporary issues. Some of the remarkable points or arguments discussed in the book are as follows.

Certainly, this work may be regarded to a certain extent as a sort of record of historical events of the last journey of Buddha. But some of the accounts contained in it obviously don't match with historical fact. For instance, according to the second chapter of MPS, Buddha met Sāriputta on the way at Nālandā and talked with him, perhaps this was only to show that the legendary excellence of his intelligence was far inferior to that of Buddha, but there is sufficient textual evidence in other texts that attests he had died before Gotama Buddha. In addition, there are other passages that seem to show an intentional distortion of the actual events. For instance, the MPS “reports” that Buddha blamed Ānanda no less than sixteen times for his failure to request Buddha to extend his life. Either case may possibly be explained by postulating the intention of the compiler(s) of the text to lower the reputation of both disciples. When we analyze how the MPS was compiled as it is, it would be very important to consider the possibility of underlying tensions among influential major disciples after the death of Buddha.

On the other hand, it would be difficult to determine to what extent one should regard stories of miracles and mysterious events as the results of later development of deification of Buddha. In my view, it should be quite probable that even during his lifetime, some notions of miracles had already been associated with the Buddha. There is no doubt, however, that it does not matter to the relevance of Buddha’s teaching whether you believe those miracles or not. According to Dr. Nakamura, Gotama Buddha’s original teaching was quite simple: it was just “live a good life as a man.” The present author emphasizes the necessity of reevaluating Nakamura’s idea of “Buddha as a human” in terms of his inquiry into the potentiality of Buddha’s teaching as a living philosophy instead of his historical approach.

The sixth chapter discusses the number of Sāla trees described on various works of nirvana relief or painting and proposes a tentative solution to the question why the number of Sāla trees increased from one pair to four pairs in later periods. The same chapter also refers to Daisetsu Suzuki. The author tries to throw a new light on the significance of Buddhist thought as a way of living serenely by paying special attention to M. Okamura’s description of how Daisetsu lead a peaceful life.

(Written by MARUI Hiroshi, Professor, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology / 2017)

Find a book

Find a book