Title

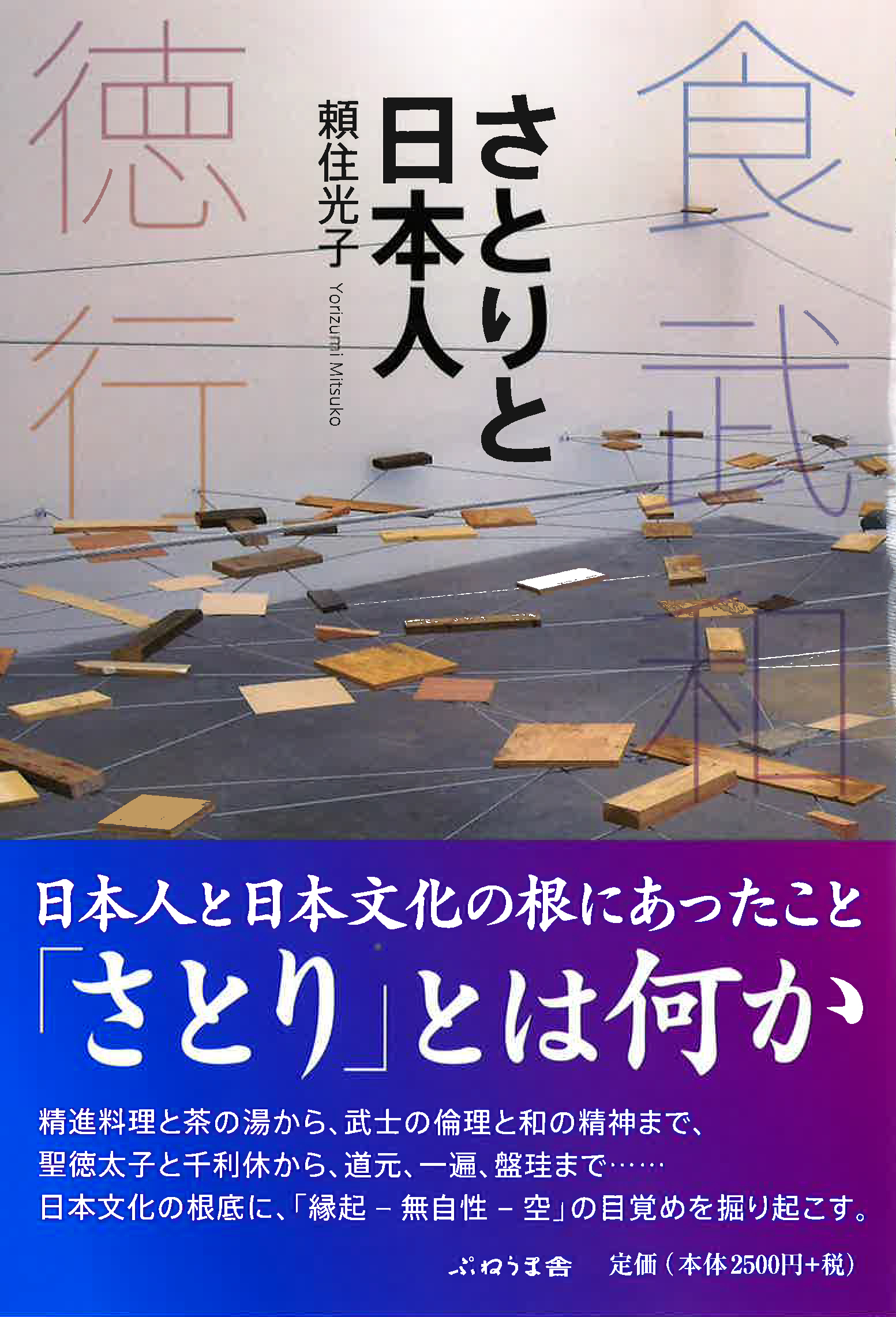

Satori to Nihon-jin (Enlightenment and the Japanese: Diet, Samurai, Harmony, Virtue, and Practice)

Size

256 pages, 127x188mm

Language

Japanese

Released

February 24, 2017

ISBN

978-4-906791-66-8

Published by

PNEUMASHA Co.

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

This book is an attempt to trace in various ways what people living in this Japanese archipelago and thinking in Japanese have learnt from Buddhism, which entered Japan as a body of thought and culture of foreign provenance, and how they opened up new horizons in their views of the world and human beings.

The starting point of Buddhism is the “enlightenment” or “awakening” that the Buddha Śākyamuni experienced beneath the bodhi tree. The teachings that he mastered through his experience of “enlightenment” spread widely from South Asia as far as East Asia. According to various sources, Chinese Buddhism was transmitted to Japan via the Korean peninsula in the middle of the sixth century. The form of Buddhism that was transmitted to Japan had changed considerably from the original teachings of Śākyamuni. Nonetheless, a single thread of thought had been passed down uninterruptedly and led to the creation of various cultures and ideas. I consider this single thread of thought to have consisted of the basic doctrines of Buddhism, namely, “no-self,” “impermanence,” “emptiness,” and “dependent co-arising.” The “enlightenment” that represents the starting point of Buddhism is the experience of mastering these doctrines in one’s own person.

As is frequently noted in this book, “no-self” means that nothing, including oneself, is fixed and unchanging, while “impermanence” means that everything is transient. “Emptiness” is often misunderstood to mean that everything is empty and nothing exists, but it means that there is nothing that is fixed and unchanging, and it denotes the same state as “no-self.” Why, then, does something that has no self and is impermanent and empty exist “here and now”? This is explained by “dependent co-arising.”

“Dependent co-arising” means that things come into existence in both time and space as a result of various causes, and this may be described as “relational existence.” “I,” “here and now,” am one of the nodes in a net of relationships. “I” have manifested in the way I find myself “here and now” in relationship to others, but if the relationships change, or if the “locus” changes in conjunction with changes in time and space, then “I” too will change.

This way of thinking in Buddhism is one that pursues “my” true mode of being “here and now.” But at the same time, by going more deeply into this “me,” “here and now,” it also serves to relativize the way of thinking that accepts without reservation “possession” and “control,” a way of thinking that has in the course of human history come to be regarded as perfectly normal. The Buddhist way of thinking could also be described as a way of thinking characterized by “continuity,” which does not see any division between oneself and others or between oneself and the world.

In this book, I throw into relief what Buddhism, with its distinctive way of thinking outlined above, has given to Japanese thought and culture, and I do so with reference to dietary culture, the way of the samurai, the spirit of “harmony,” the tea ceremony, the idea of “virtue,” religious practice and self-cultivation, coexistence, and so on. Of late, there has been a marked tendency in the field of research on Japanese thought for the basic and fundamental question of “What is Japanese thought?” to slip away from the consciousness of researchers because of an excessive focus on the detailed analysis of individual research topics. This book is both a modest attempt to counter this tendency and an endeavour to apply the thinking of Buddhism to the present age.

(Written by Mitsuko Yorizumi, Professor, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology / 2018)

Find a book

Find a book