Title

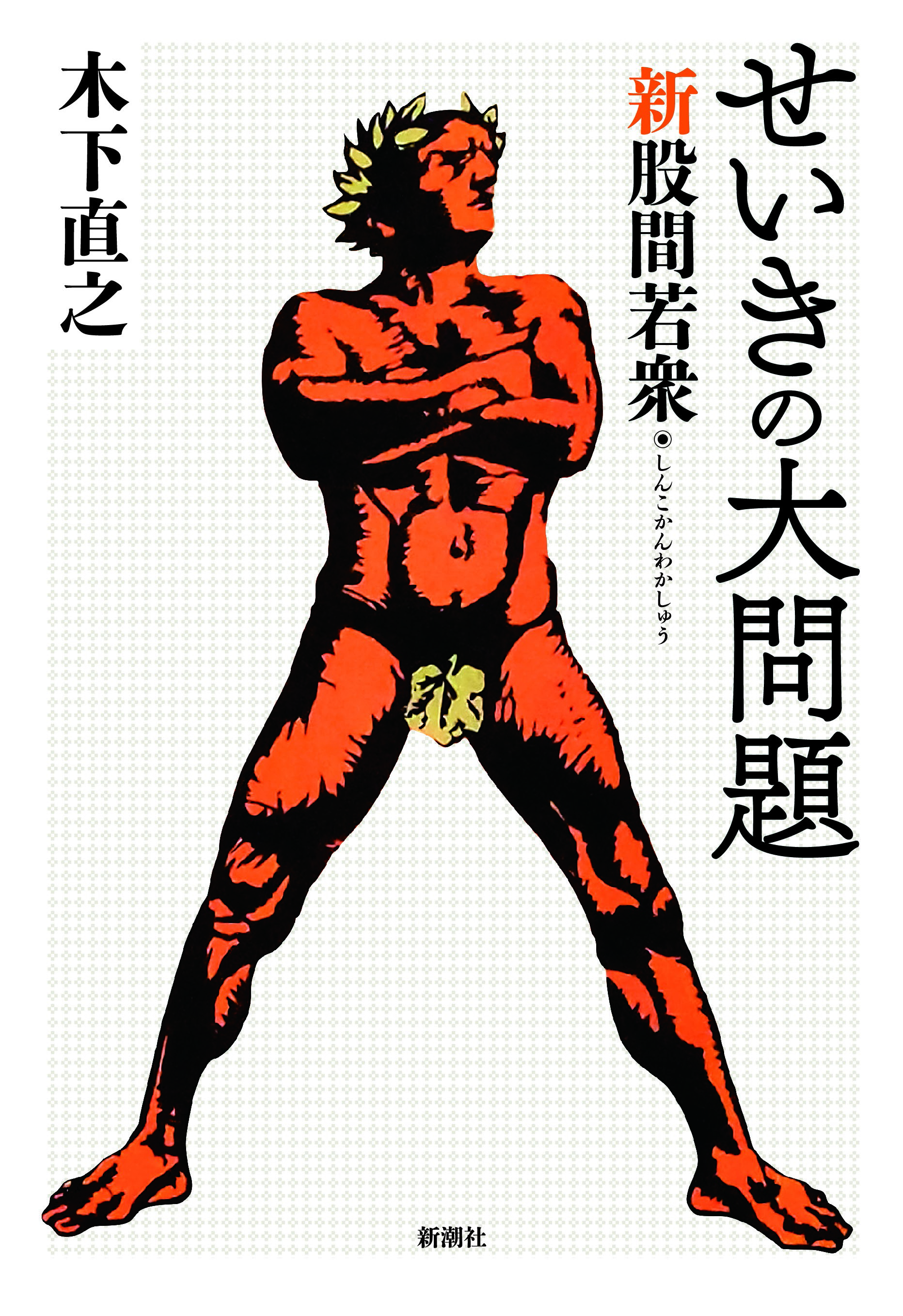

Seiki no Dai-Mondai (Arse Publica: An “undercover privates” investigation)

Size

207 pages, 127x188mm

Language

Japanese

Released

April 27, 2017

ISBN

978-4-10-332132-3

Published by

Shinchosha Publishing Co., Ltd.

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

The Japanese title of this book (The Great “Seiki” Problem), comes from Chapter 3, “Japanese art, below the waist,” in which I present an argument about a particular painter, genitals, and centuries. It is essentially a pun, as all three of those words are pronounced seiki in Japanese. Somewhere along the way, I started to write about serious issues in a flippant way, which is an internal pressure I cannot resist when I get to the final stages of writing a book and have to decide on a title. The hope that someone will sneak my glib title into the footnote or bibliography of their very serious thesis gets the better of me in the end.

So, what are the serious issues at hand here?

The first seiki is Seiki KURODA, a Meiji-era (1868–1912) artist who painted in the Western style. He went to Paris to study law, became a painter instead, and returned to Japan in 1893, whereupon he tried to get Japanese audiences to see Western nudes as art. However, he was not very successful, and nudes remained obscene pictures of naked bodies. This was during a time when shunga (Japanese erotic paintings) were still familiar, albeit already banned.

That brings us to the second seiki, genitals, which were particularly problematized. The word seiki was not used at the time. Medical specialists called them zōkaki (“mechanisms of Creation”) or seishoku-ki (“reproductive organs”), which were medical terms, and those who discussed Kuroda’s nudes called them kyokubu (“certain parts”) and inbu (“shadow parts”). The discussion of how the meeting point of our two legs came to be this big of an issue goes all the way back to the Old Testament when there were still only two people on Earth.

Finally, we have the third seiki, “century,” which is the meaning that goes most naturally with the book’s original title. The reason I think it is literally a “major issue of the century” is that in 1901, at the very beginning of the twentieth century, Kuroda’s Female nude (in the collection of the Seikadō Bunko Art Museum) was displayed at an exhibition of the Hakubakai artists’ society. The painting was censured by the police, and a cloth was wrapped around its lower half to hide the lower half of the female subject—a rather odd sight. I call this the Loincloth Incident.

Is the overlapping occurrence of these three seikis unique to a Meiji-era Japan that was pushing its limits to catch up to the West? Not at all. In the summer of 2014, the police ordered the removal of a work by photographer Ryūdai TAKANO that was on display in an exhibition room at the Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art. Following discussions between Takano and the museum, the lower halves of the two nude male subjects were covered with a cloth. A major twentieth-century problem was now also a major twenty-first-century problem.

Thus, the dichotomy between art and obscenity was established over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and, on top of that, it is still alive and well in contemporary Japanese society, as I show in Chapter 6, “On the dicksplay and dickstribution of obscene materials.” The same summer as the Takano incident, the artist Rokudenashiko (Megumi IGARASHI) was arrested and placed under police detention—unlike the photographer—and Chapter 6 follows the story of her indictment, trial, and sentencing. It also contains the “Opinion on the Rokudenashiko trial,” which was requested by the defense counsel and submitted to the Tokyo District Court.

I have not neglected to include shunga, either. Modern society has tried so hard to hide its private parts, but the shunga of pre-modern Japan used to celebrate and even exaggerate them. This book is an attempt to understand the continuity and discontinuity between these two societies.

(Written by Naoyuki Kinoshita, Professor, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology / 2018)

Find a book

Find a book