Title

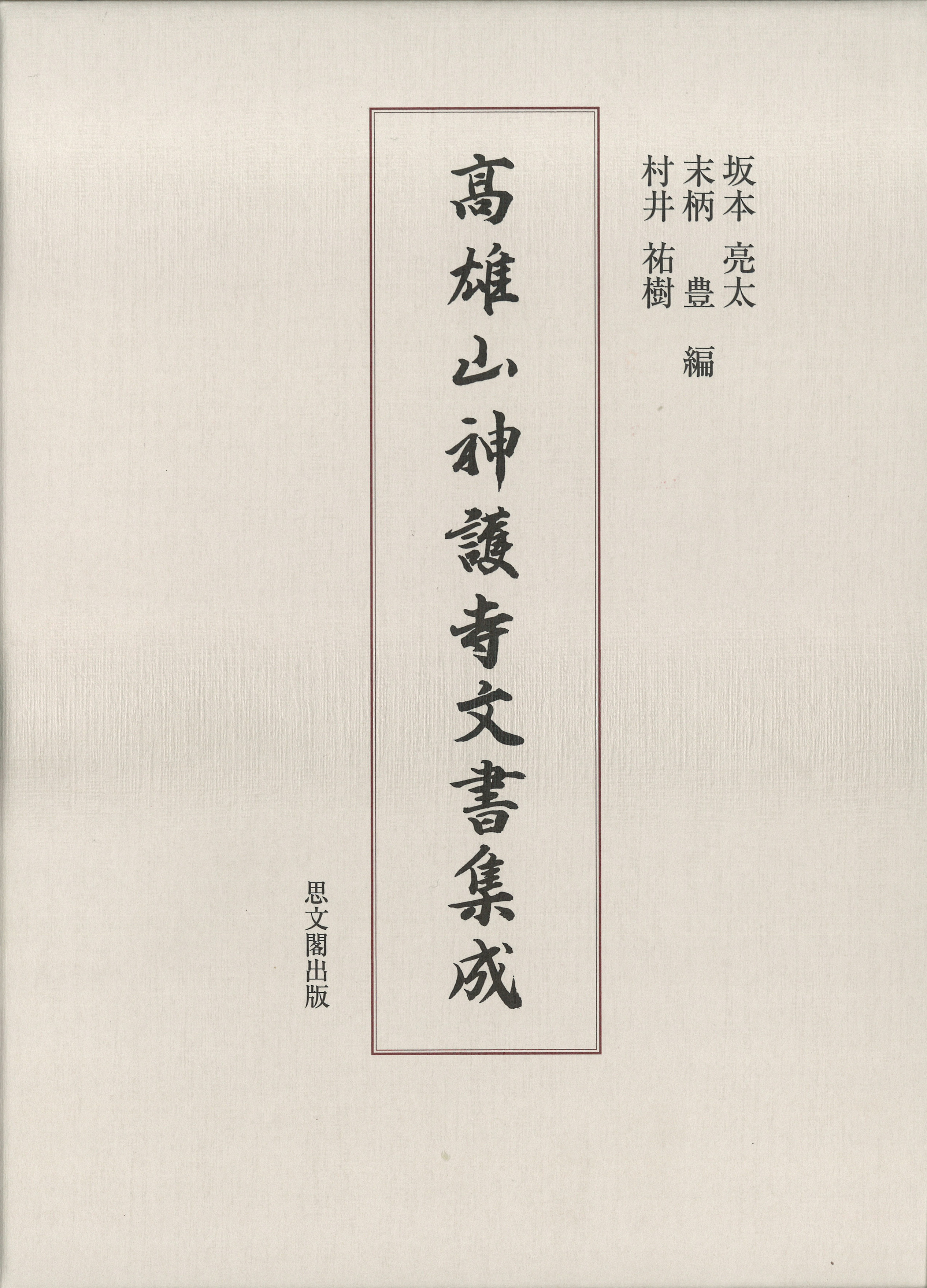

Takaosan Jingoji Monjo Syusei (Collected Documents of Takaosan Jingoji)

Size

626 pages, A5 format

Language

Japanese

Released

March, 2017

ISBN

978-4-7842-1883-7

Published by

Shibunkaku CO., LTD.

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

This book is, in a word, a collection of historical sources consisting of documents and records of the ancient and medieval periods that were preserved in the temple Jingoji. The operative phrase here is “were preserved” rather than “are preserved.”

Takaosan Jingoji, situated in the northwest sector of Kyoto and famous for its autumn leaves, has a history of about 1,200 years as a temple of the Shingon sect. Although parts of the temple were destroyed by fire several times in the late Heian period and during the Sengoku period, it still has many cultural properties mentioned in secondary education textbooks and so on, starting with the Kanjō rekimei in Kūkai’s own hand and a portrait said to be of Minamoto no Yoritomo. Each year during Golden Week in May, even national treasures and important cultural properties that are usually kept at national museums are brought back to the temple, where they are aired and put on public display. If one has the opportunity, it is well worth visiting Jingoji to view them while enjoying the scenic beauty of the temple enveloped in the fresh verdure of spring.

The cultural properties aired at this time include documents dating from the Insei to Muromachi periods that have been designated important cultural properties under the collective title of Jingoji Documents (arranged in the form of 23 handscrolls and 1 hanging scroll), and the majority of these (274 documents in 19 handscrolls and 1 hanging scroll) were typeset and published in the journal Shirin in the 1940s. In compiling anew a collection of documents related to Jingoji, some innovations have naturally been introduced.

Focusing primarily on the period until the sixteenth century, this book not only contains the Jingoji Documents (23 handscrolls and 1 hanging scroll) and other documents currently preserved at Jingoji, but it also includes documents that were formerly held by Jingoji but are today held elsewhere and documents known to have been sent to Jingoji, the latter of which have been included on the basis of copies kept by the senders, and this has been done in an attempt to bring together as many documents as possible that would have been formerly preserved at Jingoji. In order to differentiate this compilation from the previously published Jingoji Documents and indicate that the documents were collected and brought together in this volume, it was decided to call this book Collected Documents of Takaosan Jingoji. This editorial policy was based on the recognition that while the amount of information contained in individual documents is by no means large, there are many instances in which our understanding of individual documents changes or deepens by bringing together all the documents formerly held by Jingoji.

Among the 496 documents contained in this volume, 302 documents are currently preserved at Jingoji and 194 documents were formerly held by Jingoji. Documents from the ancient and medieval periods that have been preserved over a long period of time down to the present day—not just those of Jingoji—are not necessarily held where they were originally preserved. Soon after the time when the documents were produced there were already instances in which documents were transferred in conjunction with the movements of monks between temples. Further, once documents lost their current usefulness, already in the Edo period they were often taken from temples as antiquarian objects or sometimes as material for recycled paper. Major social changes from the Meiji era onwards also caused further movement of documents. Many of the documents held by museums and private collectors are documents that have become separated from the groups of documents to which they originally belonged.

The efforts involved in seeking out documents formerly held by Jingoji and restoring the corpus of documents that formerly existed could be described as a task similar to piecing together a jigsaw puzzle of which the completed picture is unknown and many pieces are missing. Therefore, with this book serving as a reference, it will be possible for readers to take up the task of seeking out new pieces and continuing the restoration of Jingoji’s former documents.

(Written by Yutaka Suegara, Associate Professor, Historiographical Institute / 2018)

Find a book

Find a book