Title

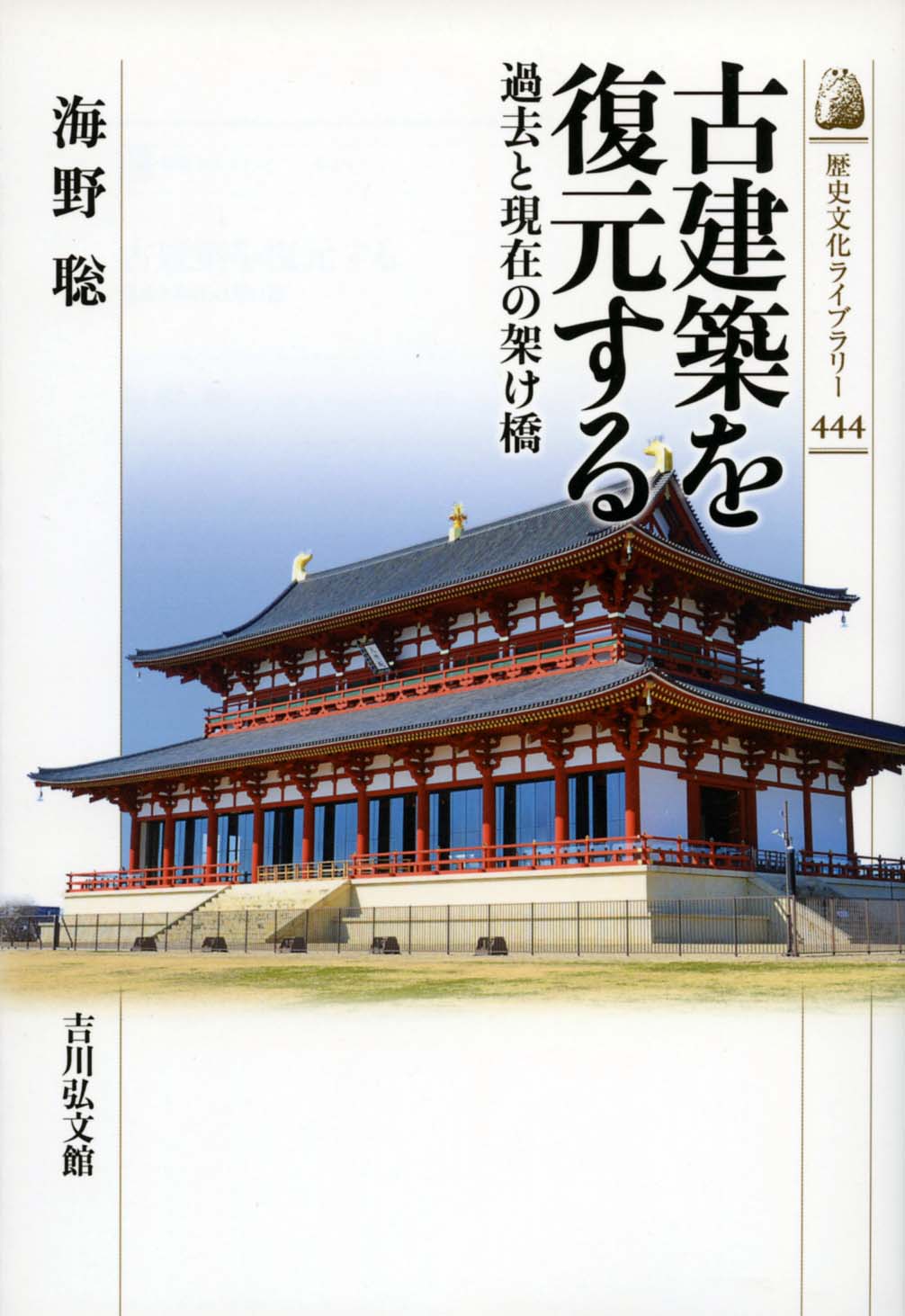

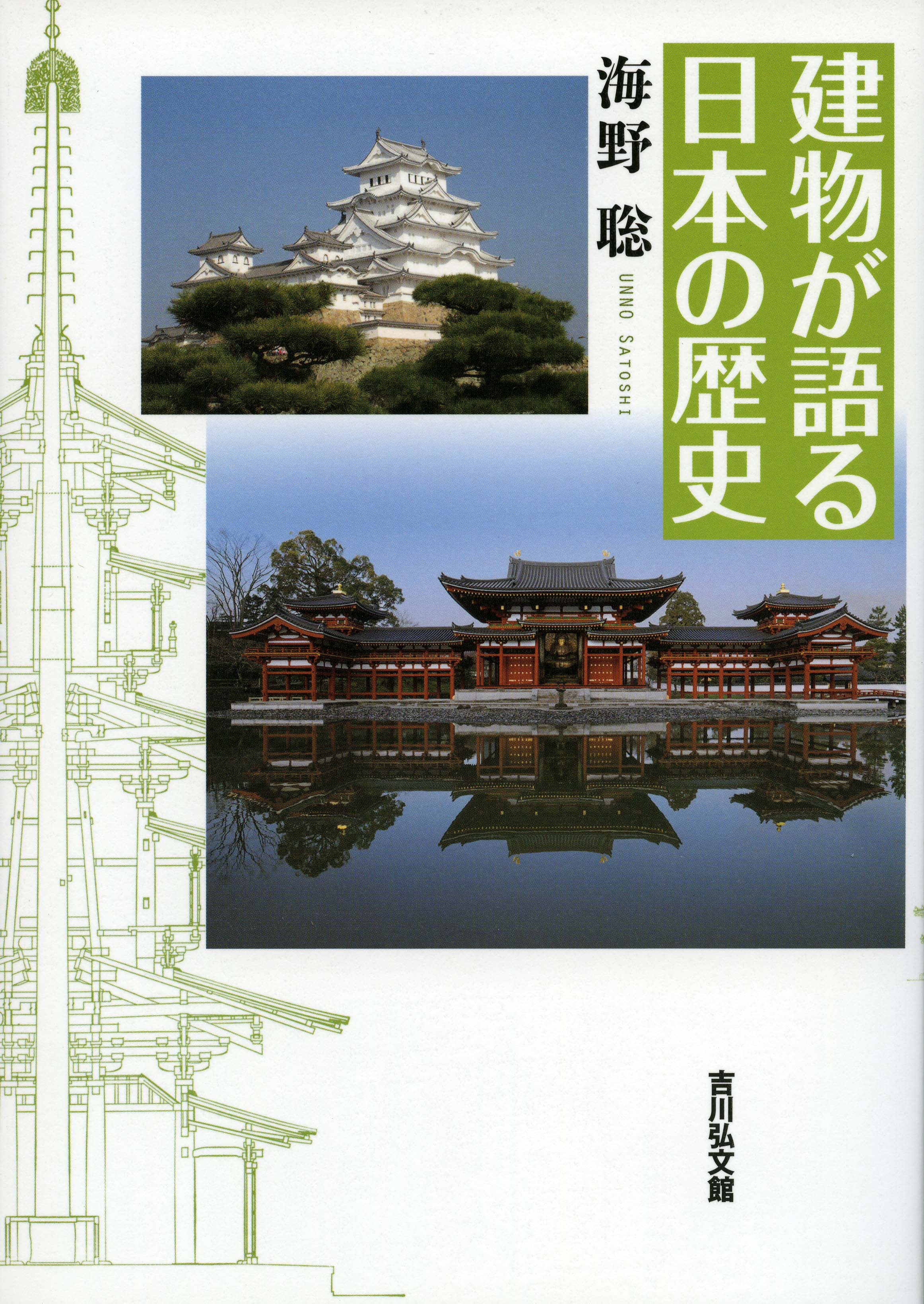

Tatemono ga kataru Nihon no Rekishi (Japanese History, as Expressed by Buildings)

Size

336 pages, A5 format

Language

Japanese

Released

July 24, 2018

ISBN

9784642083362

Published by

Yoshikawa Kobunkan

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

The history of architecture has been studied by focusing on the development of the structures and designs of buildings, the use of space, and so on. In contrast, the significance and symbolism of buildings themselves have rarely been topics of direct discussion. Thus, this book not only traces buildings from the perspectives of historical technology or functionality between their origins and early modern times, but it also grasps their societal position in order to portray their historical significance. This book is, of course, partially a textbook on the history of Japanese architecture. Yet, it was also written to provide non-architect readers with new historical perspectives by utilizing buildings.

Ancient palaces, castle towns, and the like have traditionally symbolized the Ritsuryō State. Similarly, keeps constructed on castles were instruments enforcing the rule of the samurai family administration. Likewise, the tatami-room style and tatami-room ornamentation of the Shoin-style architecture served as instruments of power. Religious architecture, including the Great Buddha Hall at Tōdaiji Temple, was often created as displays of authority.

On the contrary, relatively weak demarcations of space (e.g., level differences of the floor, and the forms of the ceilings) are defined as architectural expression. These were first interpreted as evidence of common understanding within a shared cultural sphere. They reveal the context in which Japanese architecture was created. In contrast, Edo Period theaters, richly ornamented temples, and shrines visited by pilgrims demonstrated the rise of common peoples’ power. As evidenced by these trends, buildings have often been so-called “products of history.”

The locations and forms of buildings interweave tradition and reformation. Toyotomi Hidoyoshi’s Jurakudai palace was constructed on the former site of the Heian Period palace (Daidairi). In the Meiji Period, official residences, schools, and other public buildings were constructed on previous sites of castles and samurai mansions. These actions both challenged and upheld past authority.

In terms of form, Tōdaiji Temple was restored with new style during the middle ages. Conversely, Kōfuku-ji Temple maintained its Nara Period scale and ancient form. In opposition, a new religion (the Zen sect) constructed its buildings by applying new designs and structures. Their goal was to emphasize Zen’s differences from older sects through the design of its buildings. The erection of the Zen temples was particularly linked to the rule of the samurai family. Together, their erection and the Five Mountain System were especially representative of authority.

Historical research has also uncovered many elements linking the past with modern times. For example, during the period of high-speed economic growth (i.e. the mid-1950s to the early-1970s), priority was on the construction of new buildings. Yet, there was inadequate planning for their maintenance. Thus, in recent years, concrete buildings from that era have reached a stage where they require maintenance. The lack of maintenance plans has caused postponement of this work. Notably, the same situation—a priority on new construction and the postponement of maintenance—occurred in the Nara Period as well. Indeed, history surely repeats itself.

Observation of materials shows that it has become increasingly difficult to obtain supplies of large-diameter timber. Currently, in the Great Buddhist Hall of Tōdaiji Temple (reconstructed during the Edo Period), columns are made of laminated wood instead of single trees. Inversely, to function structurally, beams must be solid timber. Consequently, nationwide searches for giant trees were carried out, and they were transported from Hyūga Province (now Miyazaki Prefecture). In modern times, ensuring a supply of giant timber remains difficult. Accordingly, when the Central Golden Hall of Kōfuku-ji Temple was reconstructed in 2018, column timbers were obtained from Cameroon. Repair of historical buildings necessitates such sourcing of giant timber to replace damaged members. Such problems with lumber supply and demand are deeply linked to forest industry difficulties extending beyond the field of architecture.

One example of the intersection between history and buildings is the city residence of the Maeda Clan. Originally a part of the Kaga Han (i.e. the Kaga domain and located in Ishikawa prefecture in present), this structure has now been inherited by the University of Tokyo. Here, its past form is evident in both the Red Gate and the Sanshiro Pond. The Red Gate is a particularly good example of a building that expresses characteristics of Japanese society during the Edo Period. Why do you suppose the gate was red? Also, there was more than one red gate. My hope is that each of you will find the answers in this book.

(Written by UNNO Satoshi, Associate Professor, School of Engineering / 2019)

Find a book

Find a book

eBook

eBook