Title

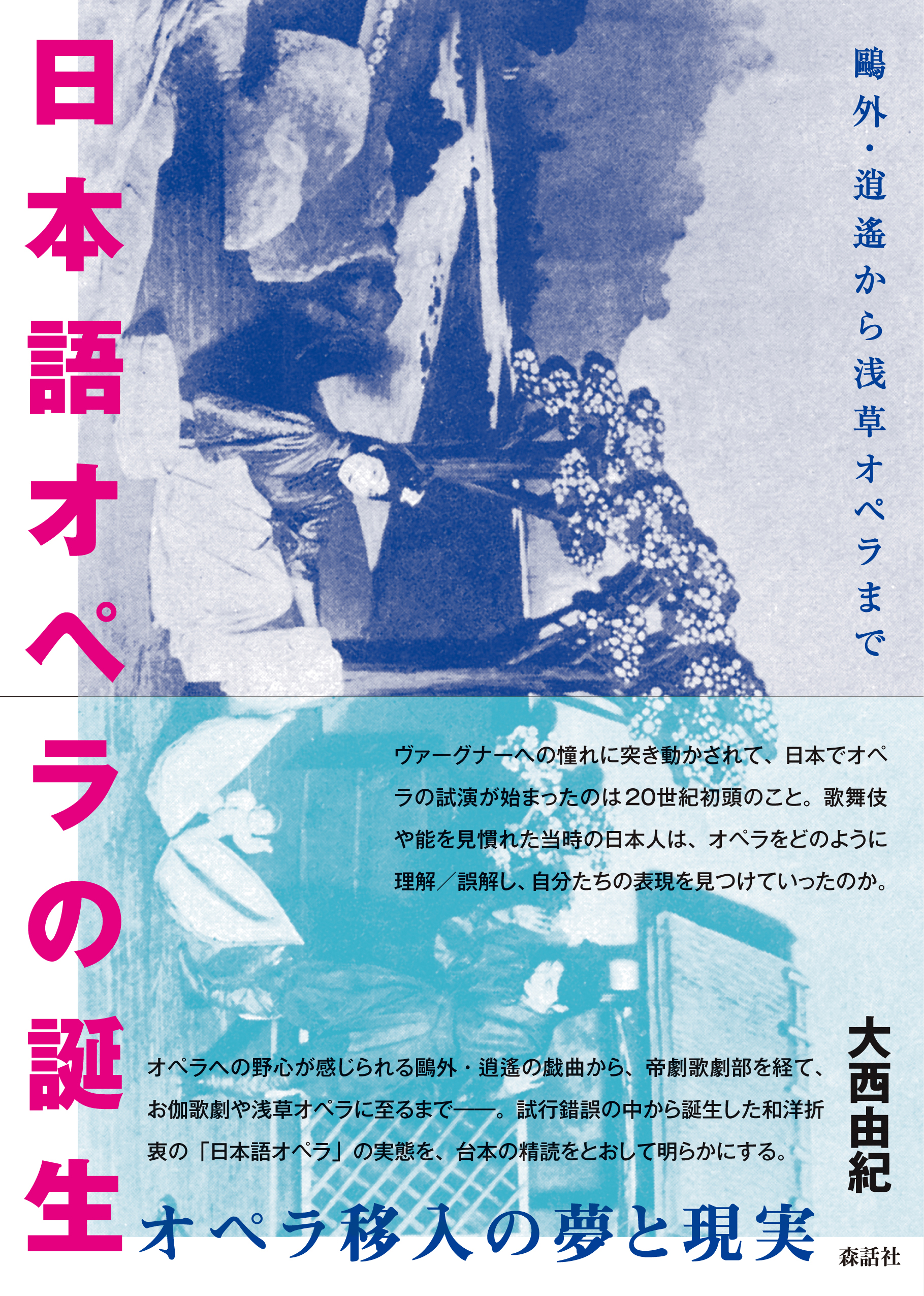

Nihongo Opera no Tanjo (The Birth of Japanese-Language Opera, 1902–1923.)

Size

544 pages, A5 format

Language

Japanese

Released

July, 2018

ISBN

978-4-86405-131-6

Published by

Shinwasha

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

One hundred years ago, the Asakusa neighborhood in Tokyo was known as the most vibrant entertainment district throughout Japan, filled with many small venues for live performances. Among traditional storytelling, martial arts performances, magic shows, freak shows, and silent movies, the audience’ s favorite were variety shows which were inaccurately called “opera.” A typical opera show in Asakusa featured musical comedies along with ballet divertissements and spoken farces. Some of the musical plays were excerpts from Western operas and operettas, and the others were newly-written sketches which incorporated famous opera arias and Western popular songs. Almost all the songs and spoken dialogue were performed in Japanese. This is surprising, considering the fact that the Japanese language is very different from European languages.

In addition to the language barriers, Japanese opera troupes faced other difficulties back in those days. To begin with, they had no model to follow after: no major Western opera company had ever come to the Far East, and recording media that could inform the hours-long opera performances did not yet exist in Japan.

So, how did the Japanese performers come to know about opera and try staging it by themselves? The story goes back for another twenty years, to the turn of the 20th century. Amid the worldwide Wagner boom, the German composer inspired scholars and artists in Japan, mainly through his prose works and libretti. Some Japanese started writing music dramas based on local myths and legends, with the aspiration of creating Japanese “national opera.” Others tried staging smaller scale German operas, with Japanese-translated lyrics, dreaming of the day they can finally perform Wagner’s massive works. At first, they were booed and jeered at. After twenty years of twists and turns, Japanese-language opera finally gained public popularity in Asakusa, but it had no trace of its original form. Sadly, this boom abruptly ended in 1923, when a devastating earthquake struck Tokyo, flattened and burned all the stalls in Asakusa, and forced artists to disperse.

This book is the first monograph about Japanese-language opera, tracing the first twenty-year history of the genre. Not satisfied by just listing chronologically the titles of the pieces performed, I attend to the details of each work and provide an academic analysis of the pieces. After an overview of the libretti, scores, reviews, photos and recordings available today, I selected a dozen pieces which I found most epoch-making or typical, and do a close reading to answer questions such as: what were the stories about; what style did they follow; are there any rules to distinguish between sung and spoken lines; where did the singers sing their parts, onstage or offstage; and so on.

One notable finding from these thorough analyses is that the earliest Japanese opera libretti followed the style of Kabuki scripts, in which actors on stage recite lines of what characters actually say, while offstage singers reveal characters’ inner thoughts. This suggests that the long and vast theater tradition in Japan had significant influences on opera reception, contrasting with previous studies’ view of opera in Japan as being transplanted to an uncultivated land.

As seen above, the nine chapters of this book shed new light on Japanese-language opera. Although the genre has been often disdained as less authentic than Western “original” opera, this book rediscovers it as a creative attempt of accepting other cultures and reflecting on one’s own.

(Written by ONISHI Yuki, Assistant Professor, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences / 2019)

Related Info

Encouragement Award of the Kawatake Award, Japanese Society for Theatre Research (2019)

http://www.jstr.org/outline/outline05.html

Japan Comparative Literature Association Prize, Japan Comparative Literature Association (2019)

http://www.nihon-hikaku.org/activity/award.html

Find a book

Find a book