Title

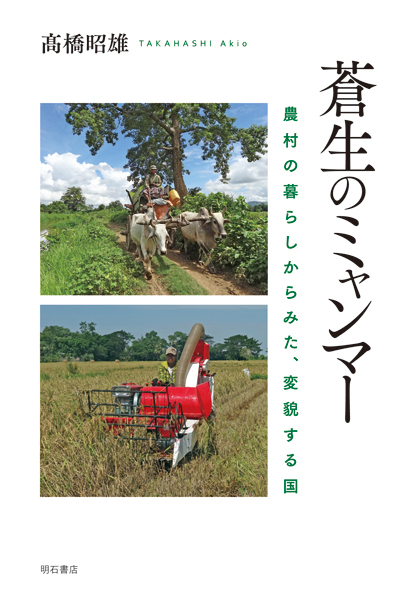

Sousei no Myanmar (The People’s Myanmar - A country in transformation from the perspective of village life)

Size

212 pages, 127x188mm

Language

Japanese

Released

March 20, 2018

ISBN

9784750346489

Published by

Akashi Shoten

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

In 1986, I made my first visit to a rural village in the present-day Republic of the Union of Myanmar, which was known as the Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma at the time. Since then, I have visited more than 200 villages bearing questionnaires that I developed in the Myanmar language (Burmese) and conducting interviews with over 10,000 people. Apart from myself, there are no other researchers in the world who have been conducting such continuous and extensive research on Myanmar.

As I specialize in economics, my published books and papers report on my various discoveries about and new insights into the land systems, agricultural production, off-farm employment, farming economies, employment, economic hierarchies, and agricultural policies of rural villages in Myanmar using economic analyses based on the aforementioned questionnaires. However, this book steers away from the detailed statistics of these questionnaires and is written with the intention of placing the everyday lives of people living in rural villages in Myanmar within the broader context of the nation’s policies, land system, religions, democratization, and modernization. This book aims to depict the unexpected and raw realities—that formulating a questionnaire does not prepare one for—within the historical context of modern Myanmar.

Chapter 1 outlines the basic structure of rural villages, in which there are many non-farm households despite Myanmar being an agricultural country; changes in agriculture, particularly in areas wherein rice has been decreasing in importance; and the modernization of rural villages, which has recently begun. Chapter 2 addresses village politics, and provides a critical analysis of the first village election after 25 years, farmers’ associations, non-governmental organizations that support the democratization of rural villages, and the agricultural policies of the National League for Democracy. Chapter 3 describes various forms of modernization and changes in a village’s socioeconomic life, such as de-agrarianization, motorization, electronization, informatization, the development of the free movement of people and commodities, and tourismization. In Chapter 4, the focus shifts from the village society to individual villagers and describes the relationship between each villager’s life and the modern history of Myanmar.

In Myanmar, 90 percent of the population consists of Theravada Buddhists. Chapter 5 presents case studies regarding the economic effects of Buddhism in villages—data that are not included in the GDP. Chapter 6 examines the socioeconomy surrounding the various types of agricultural crops produced in Myanmar, such as beans, tobacco, watermelon, and most crucially, rice. In Chapter 7, I describe people’s responses to the civil war, which is still ongoing with frequent flare-ups, as well as the severe floods as objectively as possible, although I was caught up in these myself.

Finally, Chapter 8 provides a theoretical analysis including inheritance customs, irrigation, the history of the land system, rural organizations, and existing concepts and common presumptions regarding villages are questioned here. Instead of concluding with a mere description of the region, I think that turning thorough and detailed fieldwork into theory brings great satisfaction and is the responsibility of a regional studies researcher.

(Written by TAKAHASHI Akio, Professor, Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia / 2019)

Find a book

Find a book