Title

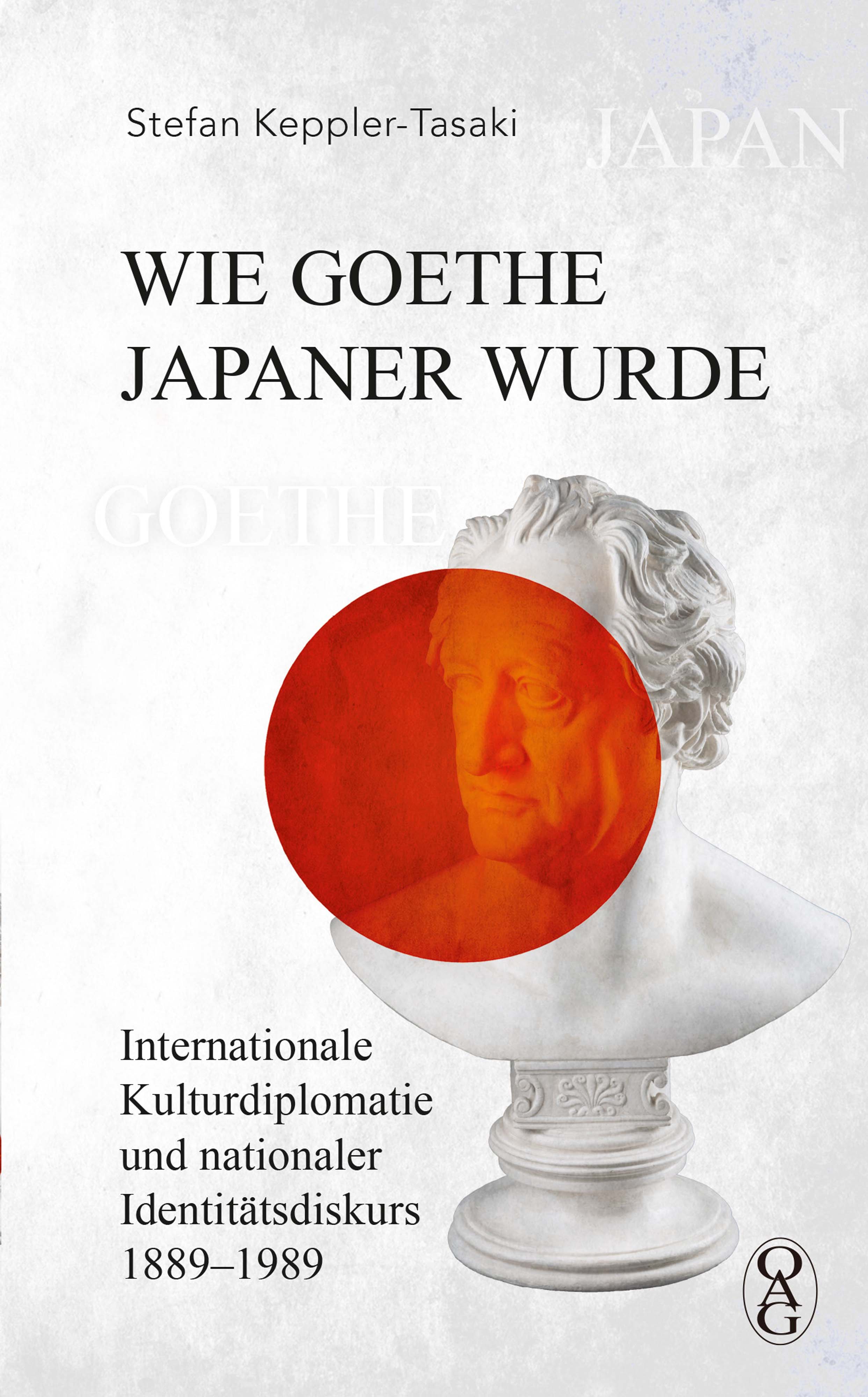

Wie Goethe Japaner wurde. (How Goethe Became Japanese. - Cultural Diplomacy and National Identity, 1889–1989)

Size

191 pages

Language

German

Released

2020

ISBN

978-3-86205-668-2

Published by

Iudicium Verlag

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

This is a book about world literature and how it can replicate the identity-forming effects of national literature for cultures beyond the originating culture. In German identity discourse, Goethe had been regarded as a vital source for the German unification process in the 19th century because his vastly acknowledged work united Germans as an audience, and his venerated persona served as a kind of first all-German sovereign. Yet, another author who famously contributed to German national identity during the century of nation building is Shakespeare. The German Romantics claimed the Bard’s work to be a true mirror of the rich German mind. “He is ours,” they said. “Hamlet is Germany,” was a sweeping slogan of the national movement. How Shakespeare – in that sense – became German, is a well-studied subject of Comparative Literature. A case to make is how similar processes of cultural appropriation or “nostrification” happened to Goethe in Japan, i.e., how Goethe became Japanese.

What is Japanese about Japan? Japanese intellectuals made much use of Goethe to pursue this question and to address the culture in which they lived. This is quite obvious in the life and work of Mori Ogai, Japan’s most prominent writer around 1900, alongside Natsume Soseki, since he spent four years of his early career in Germany, namely in Berlin, and became the foremost Japanese translator of Goethe’s works. In his ambition to grow to the first national author of modern Japan, he followed Goethe’s example on several levels. Ogai’s very first rendering of a Goethe text, the poem “Know’st thou the land” in 1889, deals explicitly with the search for a country whose outline appears only vaguely between the clouds in the sky. Ogai relived Goethe’s life as a man of letters, of science, and of the state. He blurred the boundaries between Goethe’s texts and his own production, most prominently in the case of his congenial translation of the epic tragedy Faust that he published in 1913 without even mentioning Goethe’s name on the title page.

The late Ogai had an influential group of followers, including Kinoshita Mokutaro, known as “Ogai the Second,” who used Goethe’s sublime depiction of rural and urban landscapes to discover the proverbial beauty of Japan and a way to articulate it. The so-called Japanese Romantics, a largely Germanophile group of young intellectuals in the 1930s, further politicized this technique, for example, by making use of Goethe’s invocation of the eternal city of Rome to revive the spirit of the ancient Japanese capital Nara. Two ardently eloquent and immensely successful works here are Kamei Katsuichiro’s The Education of Man. An Essay on Goethe from 1937 and Yasuda Yojuro’s essay “Why Did Werther Die?” from 1938. Both writers claimed that their reading of Goethe abetted their awakening to Japanese values.

Young Werther is only one of various characters who committed refined suicide in Goethe’s works who found a special sympathy among Japanese intellectuals and helped to channel the self-concept of Japan as the “suicide nation.” Such early deceased talents of the Meiji era as Ozaki Koyo, Kitamura Tokoku, and Matsuoka Koson contributed to the veneration of the suicidal Werther known as Wertherism (jp. Ueruteru-zumu). At the end of The Life of a Fool, Akutagawa Ryunosuke, the outstanding writer of the subsequent Taisho period, declared this autobiographical text to be his version of Goethe’s autobiography Poetry and Truth, which notoriously ends with a symbol of a life lived on the edge of catastrophe, with which Akutagawa sympathized. A whole chapter of The Life of a Fool is dedicated to Goethe’s West-Eastern Divan. While Goethe himself figures in this chapter in a Buddha-like position of tranquility, the Divan reference aims not least at the collection’s poem “Blissful Yearning” that seems to idealize suicide as The Life of a Fool, published shortly after Akutagawa’s suicide in 1927, does throughout the text. This poem, like other works of Goethe, gained a particularly regrettable use by the educated young men who prepared for kamikaze missions during the Pacific War.

Intriguing readings of Goethe’s Faust as well as of his poems and maxims served major purposes in the formulation of Zen as a philosophy. Nishida Kitaro and D. T. Suzuki, the outstanding Zen philosophers of the 20th century, made consistent use of Goethe’s work to re-invent and rephrase Buddhist thinking in a globalized world. Goethe sayings such as “One should not search for anything behind the phenomena: They themselves are the message” and “Feeling is all in all / The name is sound and smoke” were molded into modern mantras through Nishida, Suzuki, and other Buddhists. Goethe himself, a monument to freedom of the mind and of eternity in the moment, had been seen as a legitimate embodiment of the Buddha nature in Western culture.

The book concludes with case studies on the highly creative exploitation of Goethe’s Faust in Kurosawa Akira’s film masterpiece Ikiru and in Tezuku Osamu’s final, unfinished story manga Neo-Faust, as well as on Goethe as a brand of good taste and confident cosmopolitanism in the high-end men’s magazine GOETHE, published by the Tokyo-based media outlet Gentosha.

(Written by Stefan Keppler-Tasaki, Associate Professor, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology / 2020)

Table of Contents

1. Goethe, kein Deutscher?

2. Goethe, der Japaner

II. „Goethe in Japan“. Zur Wissenschaftssoziologie eines Topos

1. Japanische Germanistik mit Goethe: Kimura Kinji

2. Japanische Philosophie mit Goethe: Nishida Kitarō

3. Nach 1945: Drei Seminartraditionen

III. Goethe, Ōgai und die kulturelle Selbstverständigung Japans

1. Nationalautorschaft mit Goethe: Mori Ōgai

2. Goethe, Frankreich und Italien

IV. Goethe im japanischen Suizid-Diskurs

1. Panorama eines späten Werther-Fiebers

2. Selbsttötung mit „Stirb und werde!“

V. Der Buddha Goethe: Zu einem Motiv des Zen-Buddhismus

1. Zen als „offenbares Geheimnis“: Nishida Kitarō und Eduard Spranger

2. Weltbuddhismus: Paul Carus und D. T. Suzuki

3. „Existenz aus der Mitte“: Buddhismus und Bürgerlichkeit

4. Buddhismus als Nihilismus? Gottfried Benn

VI. Thomas Mann, Japan und die Diplomatie mit Goethe

1. An die japanische Jugend. Eine Goethe-Studie – Hintergrund und Topik

2. Pacific Palisades und die „Tokyo-Verwandten“

3. Briefwechsel mit Japanern

VII. Faust in Kurosawa Akiras Ikiru

VIII. Faust in Tezuka Osamus Neo-Faust

IX. Die Marke Goethe. Ausblick

Related Info

@German Cultural Centre (OAG Haus Tokyo) with a short video:

https://oag.jp/books/wie-goethe-japaner-wurde-internationale-kulturdiplomatie-und-nationaler-identitaetsdiskurs-1889-1989/

Find a book

Find a book