Title

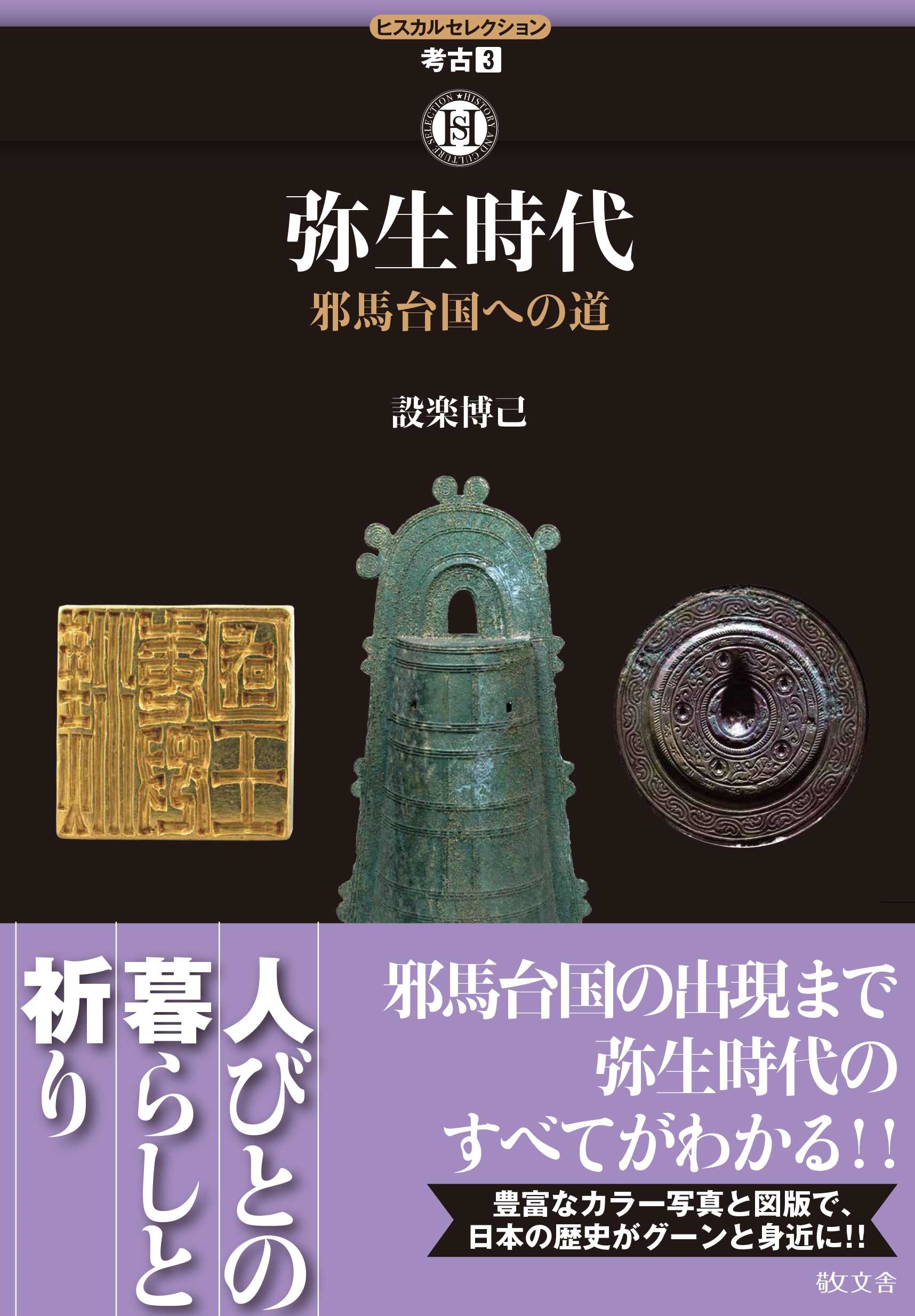

Hiscal Selection No.3 Yayoi-Jidai (The Yayoi Period - The Road to Yamatai-koku)

Size

128 pages, A5 format, softcover, full color

Language

Japanese

Released

December 04, 2019

ISBN

9784906822324

Published by

Keibunsha

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

It was in the Yayoi period that agriculture began being carried out in earnest in the Japanese archipelago. If its definition refers to the cultivation of plants, agriculture was present in the Jomon period as well. At this time, however, it was an activity wholly ancillary to hunting and gathering, and in the Japanese archipelago, it was indeed during the Yayoi period that the demand for agriculture emerged as a means of providing foodstuffs, forming the foundation of day-to-day life. The production of staple foods in modern Japan began during this period, with the introduction of wet rice cultivation being a particularly important development.

The summary stated above contains aspects regarding the nature of the Yayoi culture that can now be discussed in depth, utilizing novel points of view, as well as those we have yet to understand.

There are commentaries contained in history textbooks suggesting the presence of rice cultivation in the Jomon period as well, and that this presence might extend as far back as the early part of the period. In any case, with the emergence of new analysis methods, this is now considered to be a dubious claim. Therefore, when and how did rice cultivation enter the Japanese archipelago? Furthermore, how did it spread from there? Even if the era is accepted as a single historical period, theories and debates have emerged discussing whether its beginning might actually extend further 500 years back, and so forth, a complete shift from the presumption observed previously.

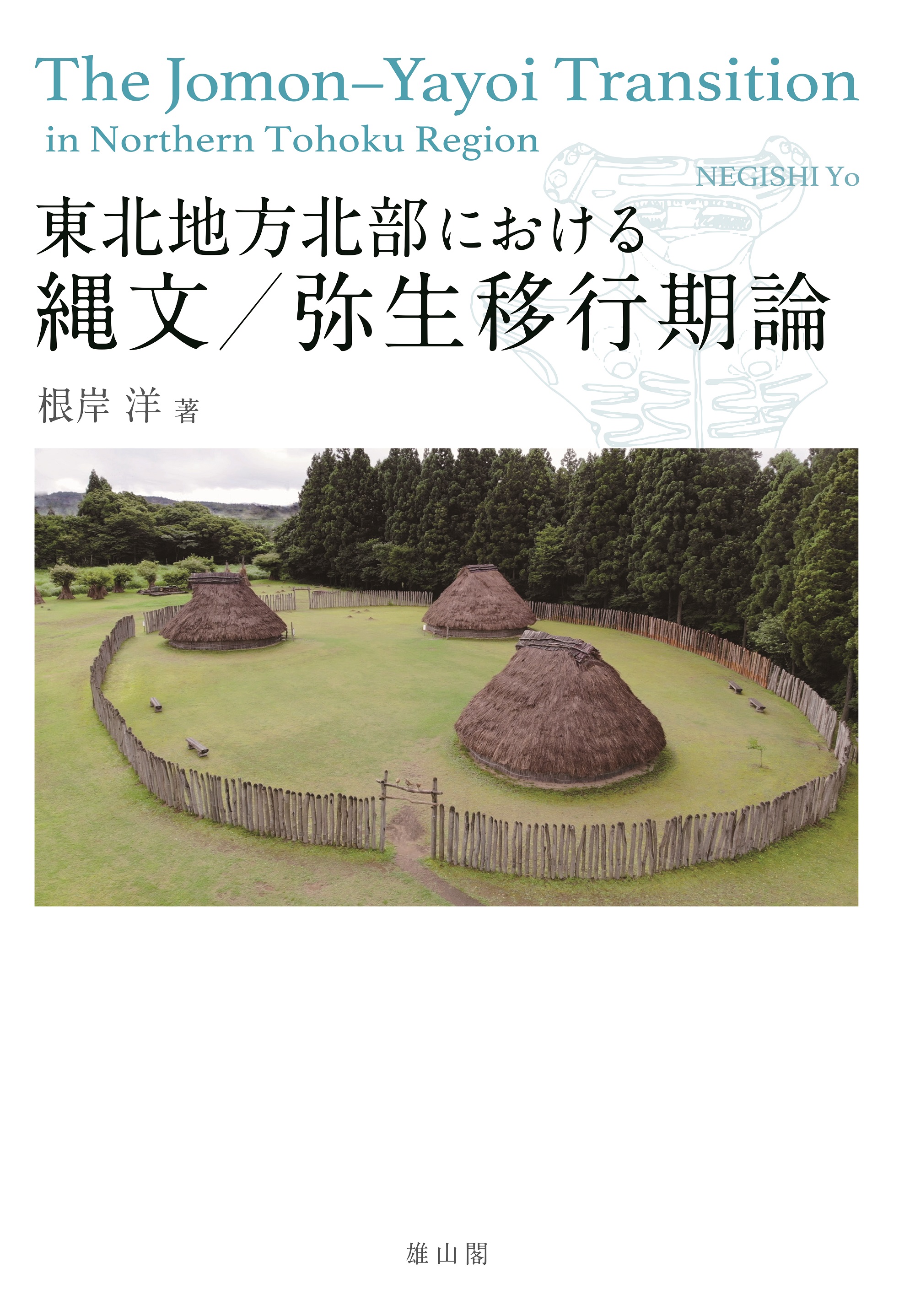

The idyllic agricultural communities recreated at Shizuoka Prefecture’s Toro Ruins were the predominant portrait of the Yayoi period settlements. However, the 1990s verification of enormous structures and large-scale moated settlements at Osaka Prefecture’s Ikegami Sone Ruins and Saga Prefecture’s Yoshinogari Ruins led to a complete reversal of this view, one that generated the Yayoi city theory, which describes these enormous moated settlements, and so forth, as also being present in the period, rather than agriculture communities alone.

In addition, the employment of dendrochronology and the new accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) carbon-14 dating method has resulted in further refinement of the Yayoi period date placement. There exists various theories and debates here as well, and one can surely state that we are currently in a time where the depiction of the Yayoi period, an era possessing extensive history, and reconsiderations therein are currently advancing.

Divided into four chapters and nine sections, this book covers the Yayoi period and its culture and society, with content ranging from personal belongings to relations with the continents across the sea, such as the production and flow of stoneware, bronzeware, and so forth, gravesite and rice cultivation conventions and rituals, and issues relating to food, clothing, and shelter at the core of the lives of those who supported this culture, the Yayoi people.

Commentary regarding various issues concerning these themes has also been included, bearing in mind new ways of thinking as well as previous approaches. As mere personal opinion would not prove interesting, though a portion of the book does contain my own interpretations, these comprise of extensive themes that allow for the Yayoi period to be studied from beginning to end to the greatest extent possible, with consideration also given to general narratives and accounts. These are the principal ideals behind this series, and it would bring me great joy if this book were to be utilized as an introductory text.

(Written by SHITARA Hiromi, Professor, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology / 2020)

Find a book

Find a book