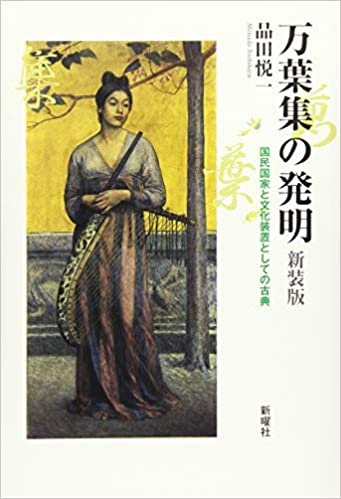

Title

New Edition Man’yōshū no Hatsumei (The Invention of Man’yōshū - Classic Text as Nation-state and Cultural Apparatus)

Size

360 pages, 127x188mm

Language

Japanese

Released

May 10, 2019

ISBN

9784788516342

Published by

Shinyosha

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

I wrote The Invention of Man’yōshū: Classic Text as Nation-state and Cultural Apparatus nineteen years ago. The book has been out of stock for some time, but past readers who heard the Prime Minister’s speech on the new era name of Reiwa took to social media saying things like “What a ridiculous explanation. Read Shinada’s book!” and the book was re-issued in a flash. In this new edition, I have added information that I learned after the publication of the first edition to the end of the book in five points as well as corrected typographical errors throughout. Otherwise, the contents are the same. The first edition of this book was acclaimed as a critical reexamination of the origins of the kind of “common knowledge” about the Man’yōshū that appeared in the Prime Minister’s speech.

In order for Japan to maintain itself as a modern nation-state, it was necessary to diffuse an awareness of “nationality” among the people. In response to this exigency, various texts written in the Japanese vernacular were selected from among the miscellaneous writings of the past and recognized as national classics. Of those classics, the Man’yōshū was from the outset bestowed with an invaluable position, and over time, this text ended up attracting an avid readership.

The “common knowledge” about the Man’yōshū as a national poetry anthology actually has two components. The first component is that “the true voices of ancient Japanese people from all classes are taken into account.” The second is that “poems by both aristocrats and the common people are rooted in the same ethno-cultural foundation.” The first component came into being in the mid-Meiji period and the second in the late Meiji period. These two components were popularized while complementing each other, and by the beginning of the Showa era (1926), they were common sense among the Japanese people.

The first component was quickly incorporated into the secondary school curriculum, and from the end of the Meiji period through the Taishō period (1912-1926), the increase in avid readers of the Man’yōshū was the primary support for the activities of poets who composed in the so-called Man’yō style. At the time that this first component was forming, Japanese poetry was regarded as a product of literary activity, and so asserting that the Man’yōshū contained poems by common people meant insisting that people living in crude huts with straw spread on the ground for flooring were literate. This assertion was clearly unrealistic. The second component had the function of patching up this inconsistency. An ideology that sought the basis for a oneness of the people in the culture of the Volk was transplanted from Germany and grafted into the Man’yōshū. In practice, the notion of “Folk Songs” (Ger. Volkslied) was nearly directly applied to the “Songs of the East” from Volume 14 and the anonymous poems such as those in Volumes 11 and 12. The short poetry known as tanka came to be regarded as the form of spontaneously generated folk songs, and the foundations for all the poetry in the Man’yōshū was sought in folk songs, including the deliberate poetry composed by aristocrats.

Due to the cumulative increase of avid readers, the image of the Man’yōshū as a national poetry anthology expanded in scope. In the early Showa era, there was an unprecedented boom in interest in the Man’yōshū, but this boom was eventually swallowed up by the troubles of the era. Several poems that are exceptions when considering the Man’yōshū as a whole were used to expand national prestige and raise martial spirit, and the text became the object of arbitrary and superficial exaggeration. For this reason, in the postwar era, there were arguments for completely rejecting the Man’yōshū. However, during postwar reconstruction, the text was widely used as material for Japanese language instruction in order to restore the self-respect of the Japanese people. For this reason, there ended up being another Man’yōshū boom in the 1960s and 1970s.

(Written by SHINADA Yoshikazu, Professor, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences / 2021)

Table of Contents

Chapter One: From the Emperor to the Common People

1. The Creation of a National Poetry Collection

2. Reexamining the Basis of Common Knowledge

3. Arrival of a Man’yōshū Printed with Metal Type

4. The Epoch of 1890

5. A Symbol of the Oneness of the Nation

Chapter Two: A Millennium and a Century: The Poetization and Nationalization of Waka

1. The Prehistory of a National Poetry Anthology

2. Shintaishi shō and the Discourse on Waka Reform

3. State Literature and National Literature

4. The Stance of Masaoka Shiki

5. A National Poetry Anthology and National Education

Chapter Three: Urheimat of the Nation: Reforms and Renovations of the Helmsmen of the National Poetry Anthology

1. Invention of the Volkslied

2. The Creation of the “Man’ȳo Man”

3. The Heresy of Itō Sachio

4. A Scripture for Educators: Shimaki Akahiko’s Reverence for the Man’yōshsū 1

5. The Development of Legends: Shimaki Akahiko’s Reverence for the Man’yōshsū 2

Conclusion

Related Info

http://jodaibungakukai.org/10_prize.html

Find a book

Find a book