Title

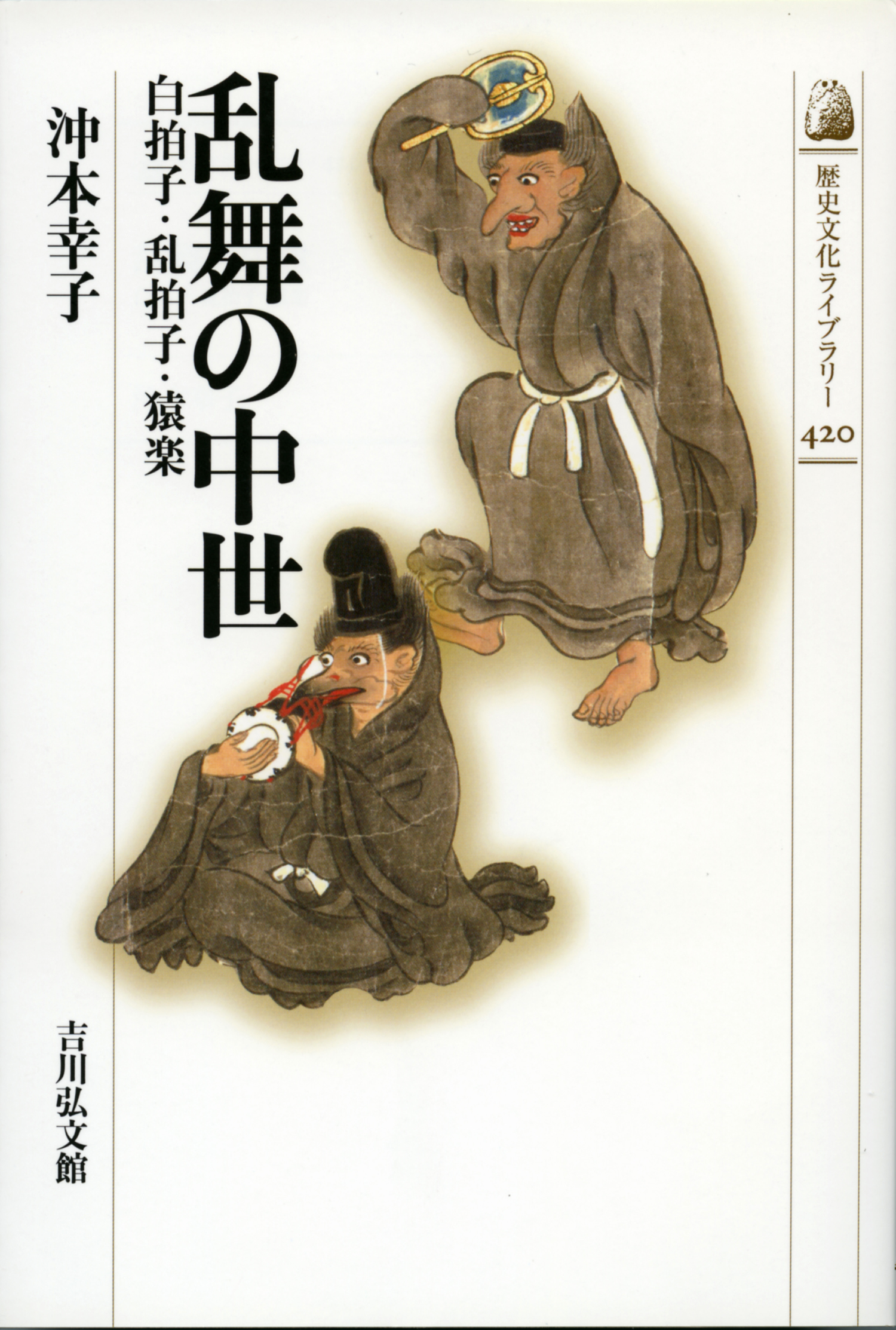

Library of History and Culture Ranbu no Chusei (Disorderly Dances, Wild Rhythms, and the Medieval Origins of Noh)

Size

206 pages, 127x188mm

Language

Japanese

Released

February 19, 2016

ISBN

9784642058209

Published by

Yoshikawa Kobunkan

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

For many audiences, traditional performing arts can likely seem quite boring. No matter what genre, however, traditional performing arts generally began as popular entertainments, at the cutting edge of once contemporary fashions. Moreover, in the past as in the present, nearly all such popular performing arts have tended to vanish soon after they first appeared. Only those genres which have received tireless support, across centuries of historical contingencies and inevitabilities, continue to survive today. To consider such traditional performing arts, then, is to think about the power to transcend time.

In this book, I have turned my attention to the beginnings of Noh, a form of traditional theater which present-day audiences often find sleep-inducing and notoriously difficult to understand. In so doing, I have endeavored to shed light on what sorts of popular fads gave rise to Noh, along with the process whereby Noh emerged from this initially wild enthusiasm.

The story begins in the late Heian period, almost two hundred years before Kan’ami and his son Zeami, who brought Noh to completion. At the time, the capital Kyoto was in the grips of a great dancing boom and rhythms boom. Popular performing arts even found their way into the imperial court, where entertainment was centered on ceremonial court music and melody, and nobles and monks, too, danced to the new rhythms. The principal rhythms were called shirabyōshi and ranbyōshi. The word shirabyōshi may remind readers of Minamoto no Yoshitsune’s mistress Shizuka or Taira no Kiyomori’s lover Giō, but it was originally the name of a rhythm. It became popular to dance to this rhythm, and female performers such as Shizuka and Giō perfected shirabyōshi as a dance possessing a particular form and became specialists in this type of dancing.

Shirabyōshi and ranbyōshi first became popular as impromptu dances called “disorderly dances” (ranbu). The official performing arts at the court remained ceremonial music and dance, but both shirabyōshi and ranbyōshi were extremely popular at the casual after-party-like gatherings that followed official banquets. At temples, public entertainment in the form of performing arts took place after important religious services, and the star attractions were stirring performances of the ranbyōshi by monks and cute performances of the shirabyōshi by boys imitating the dancing of female performers.

The key point of this book is that it was the prototype of “Okina,” the roots of Noh, that recreated these contemporary popular performing arts of shirabyōshi and ranbyōshi as a single performing art. “Okina” has until now been discussed primarily from the viewpoint of intellectual history. In contrast, I have tried to bring to the fore the form of the original “Okina” as a performing art on the basis of “Okina” as it lives on in festivals and rites throughout Japan. These forms of “Okina” found throughout Japan include vast amounts of narration that have been lost in the “Okina” of present-day Noh, as well as unexpected commonalities between performances of “Okina” across different regions. When one compares these various renditions of “Okina,” it becomes evident that the “Okina” found in today’s Noh, while certainly incorporating popular performing arts from eight hundred years ago, has been refined, sometimes by boldly discarding original aspects, as a benedictive performance that transcends time and place.

To decipher histories that have been inscribed not only in written records but within people’s bodies themselves—this is something that can be done only because performing arts from different periods have been transmitted in various localities, and herein lies one of the true joys of studying Japan’s performing arts.

(Written by OKIMOTO Yukiko, Associate Professor, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences / 2020)

Related Info

The 38th Suntory Prize for Social Sciences and Humanities (2016)

https://www.suntory.co.jp/sfnd/prize_ssah/detail/201604.html

Find a book

Find a book

eBook

eBook