Title

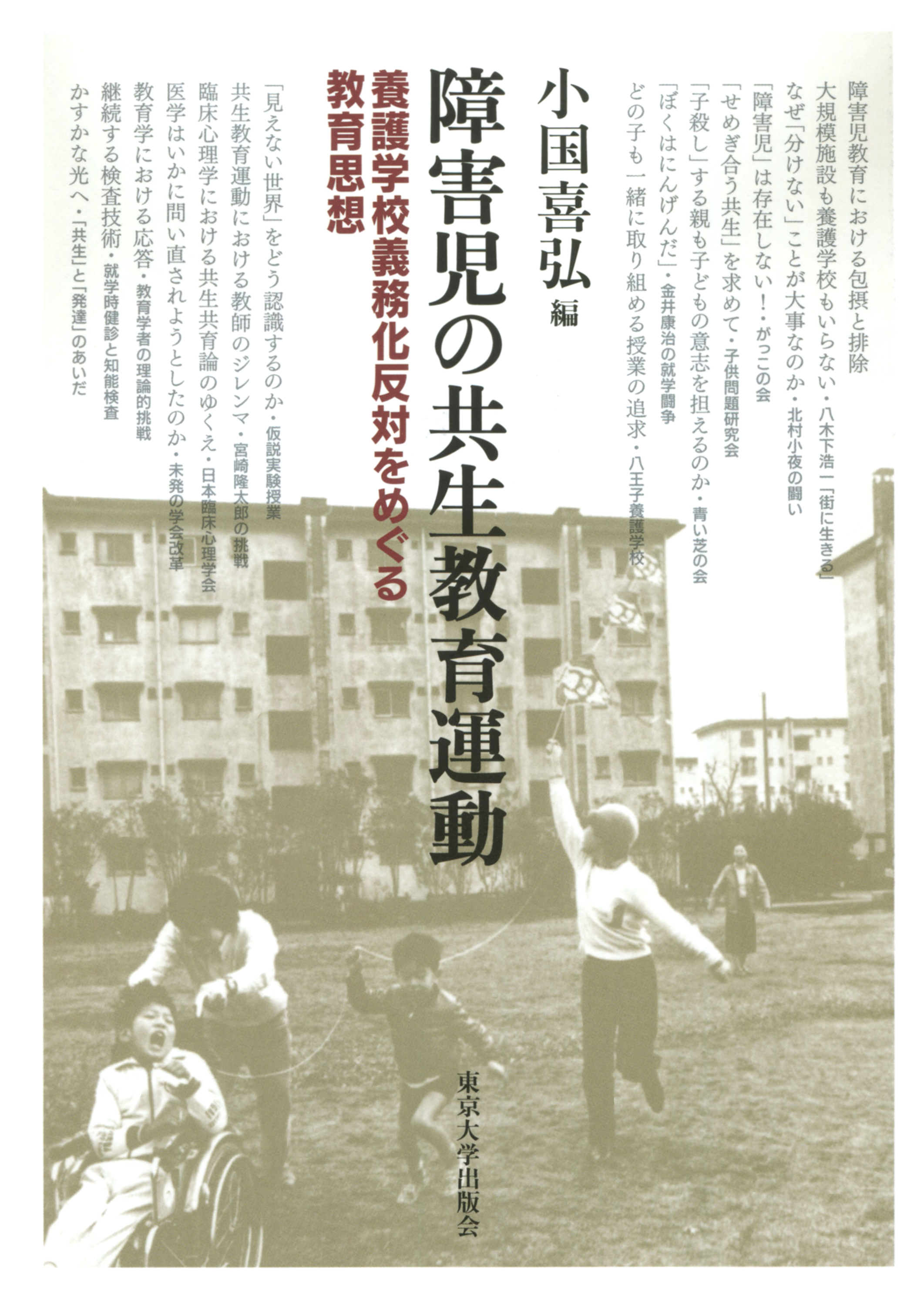

Shougai-ji no Kyousou Kyoiku Undou (The Campaign for Integrated Education for Children with Disabilities - Philosophies of Education in Opposition to Mandatory Special Schooling)

Size

352 pages, A5 format

Language

Japanese

Released

November 25, 2021

ISBN

978-4-13-051347-0

Published by

University of Tokyo Press

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

Within the Japanese school system, the number of students eligible for special schooling at the elementary and middle-school levels increases by approximately 8% every year. Despite the ratification of the Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which states that all students should ideally be educated in local mainstream classrooms, the number of people in special schools has continued to increase over the past decade.

During our graduate school seminars, we questioned why and when this education system was created, and focused on the development of mandatory special schooling for the disabled in 1979 and the counter movement surrounding the processes involved in realizing it.

Before 1979 there were children, primarily “children with severe disabilities,” for whom their guardians’ obligation to send them to school was removed or deferred. Thus, 1979 was interpreted as a step toward the realization of an inclusive society. From the education history’s point of view, it has often been understood as the completion of the modern education system in the sense of full realization of school attendance. However, in combination with mandatory special schooling, a system was introduced at that time whereby depending on the level of “development,” individuals were forcibly placed into special schools. This led to the emergence of cases where children who had previously attended local mainstream schools or who were in mainstream classes were practically forced into special schools against their wishes and those of their parents. In such situations, a movement against obligatory special schooling for the disabled developed in several different areas.

These kinds of counter-movements have been essentially overlooked as research into the history of education has primarily viewed mandatory special schooling positively.

This book examines the assertions against the introduction of mandatory special schools for those with disabilities one by one and combines all these arguments. Fortunately, most of the people involved in this movement were still alive and able to participate in interviews. As they brought up each of these movements that have been buried in history, I was surprised to find that their opposition was still as fervent today.

Allow me to cite just one of the individuals who is against mandatory special schooling, Yagishita Koichi, who lives with cerebral palsy and insisted on attending elementary school at the age of 28, framing his opposition to special schools as follows:

I think the worst thing about special schools is that people with disabilities cannot be bullied (Editor, p. 48)

Reading this in isolation may sound strange; however, Yagishita believes that if you are a human, “we live together in the same cities, we cry when we are sad, we rejoice in happy times; sometimes we fight with someone, and living our lives in this fashion is natural.” Based on this thought process, he criticized the forced placement of people in special schools as robbing people of these “natural” relationships.

In some respect, if our goal is only to improve the ability of students to perform academically, it may be efficacious to separate spaces of learning based on the degree of “development” of the individual. If the school is viewed as a space where people learn how to live, according to Yagishita’s critique, and the spaces where people learn are separated based on the type and degree of disability, then people will be robbed of the experience of “living together.”

In modern schools, the top priority is placed on improving academic ability, with efforts made to structure the spaces in which people learn around the degree of development. As we become more and more obsessed with improving academic ability, the levels of “development” of a large flock of children are becoming problematized.

It is our fervent wish that a large number of people will read this book to understand the problems in our modern education system and, in addition, the values that have been lost in our contemporary system of schooling.

(Written by KOKUNI Yoshihiro, Professor, Graduate School of Education / 2021)

Find a book

Find a book