Title

Kadokawa Sensho “Edo Ojisin no zu” o yomu (Reading the “Illustrated Scroll of the Great Edo Earthquake”)

Size

272 pages, 127x188mm

Language

Japanese

Released

January 27, 2020

ISBN

9784047036482

Published by

KADOKAWA

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

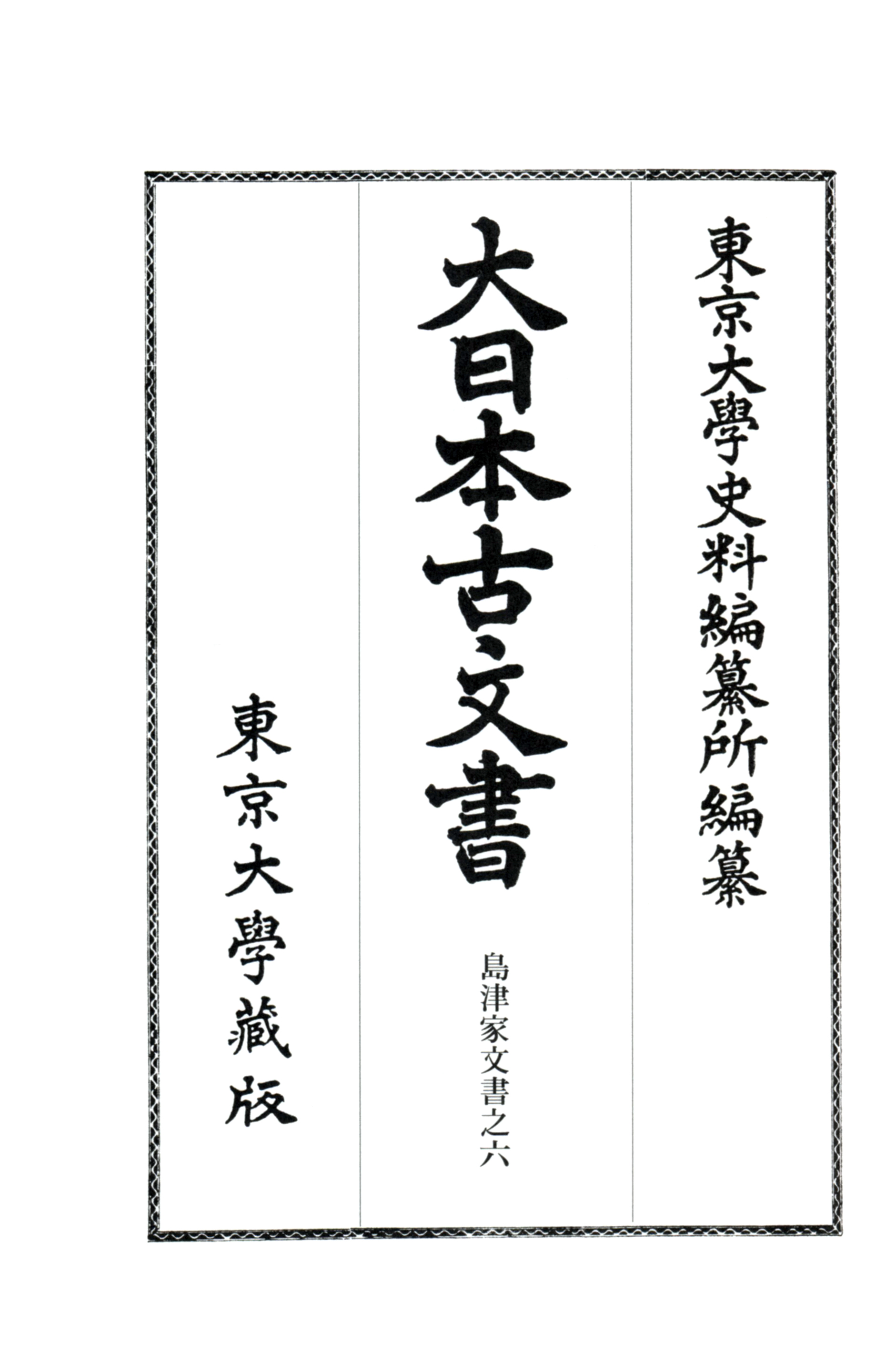

On the 2nd of the tenth month of Ansei 2 (11 November 1855), Edo (present-day Tokyo), where the shogunate was based and more than a million people lived, was struck by a strong earthquake that caused severe damage. The “Illustrated Scroll of the Great Edo Earthquake,” which draws its subject matter from this earthquake, is an illustrated handscroll that was passed down in the Shimazu family, former lords of Satsuma domain, and is now included in the Shimazu Family Collection, a national treasure held by the Historiographical Institute at the University of Tokyo. An almost identical handscroll is held by the Chester Beatty Library in Ireland, and it is said to have formerly belonged to the Konoe family, the leading family whose members were formerly eligible for the post of regent.

These two illustrated handscrolls, which might be described as twins, have no captions or painter’s signature and seal, and because of an absence of any clues to the date and circumstances of their production and the painter, in the past different parts of the handscrolls have been analyzed and assessed chiefly from the perspective of pictorial representation, and textual sources related to the handscrolls’ contents have remained virtually unexamined. The scenes depicting the terrible spectacle of the earthquake and subsequent fires make a powerful impression on the viewer, and while these two handscrolls have attracted attention as pictorial works dealing with an earthquake, they have not been examined as pictorial source material.

By reading textual sources relevant to the “Illustrated Scroll of the Great Edo Earthquake” and reconsidering the circumstances of the transmission of the version formerly in the possession of the Konoe family, this book examines the handscroll’s character as a historical source, also taking into account the relationship between the two versions. As a result, it becomes clear that these two handscrolls are not general depictions of the damage caused by an earthquake and the subsequent recovery, but are depictions of specific places and events based on historical facts.

For example, near the end of the handscroll large numbers of people are shown walking along through falling snow. When one compares this scene with the diaries of town headmen and so on, it becomes evident that it depicts people going to receive rice being distributed by the shogunate for the relief of the needy on the 20th of the twelfth month of Ansei 2, when Edo experienced a record-breaking snowfall. This depiction based on fact shows the handscroll’s high value as a historical source and also provides a clue to its date of composition.

Again, the daimyō’s residence, which takes up a large part of the handscroll, is the residence of the Satsuma domain in Shiba, and the people taking refuge in its grounds can be identified as the domanial lord Shimazu Nariakira and the lady Atsuhime. When one refers to other sources forming part of the Shimazu Family Documents, it becomes apparent that another subject taken up in this handscroll was Atsuhime’s marriage to the shogun Tokugawa Iesada, which had been further delayed by the earthquake. The reason for the transmission of virtually identical illustrated handscrolls in the Shimazu and Konoe families can also be sought in this circumstance.

In this way, by not only analyzing the images but also examining textual sources, it becomes possible to infer all sorts of historical information from the “Illustrated Scroll of the Great Edo Earthquake.” This pair of handscrolls can be understood as pictorial source material that does not simply deal with an earthquake but also conveys aspects of urban society and the political situation in the Bakumatsu period.

This attempt to decipher the “Illustrated Scroll of the Great Edo Earthquake” as pictorial source material had its beginnings in information gained from editing Saitō Gesshin’s diaries (held by the Historiographical Institute) and became possible by understanding it as a work in the collection of historical sources known as the Shimazu Family Documents. In addition, this research was pursued in the course of examining historical sources related to the Edo earthquakes of the Ansei era through my involvement in collaborative research with the Earthquake Research Institute, University of Tokyo. I shall be delighted if, through this book, readers gain an idea of the rich contents of historical sources held by the University of Tokyo and aspects of editing and studying such sources.

(Written by SUGIMORI Reiko, Associate Professor, Historiographical Institute / 2020)

Related Info

Reiko Sugimori - Unraveling history (The University of Tokyo |YouTube Dec 12, 2023)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z4Wnv5PVxIk

Find a book

Find a book

eBook

eBook