Title

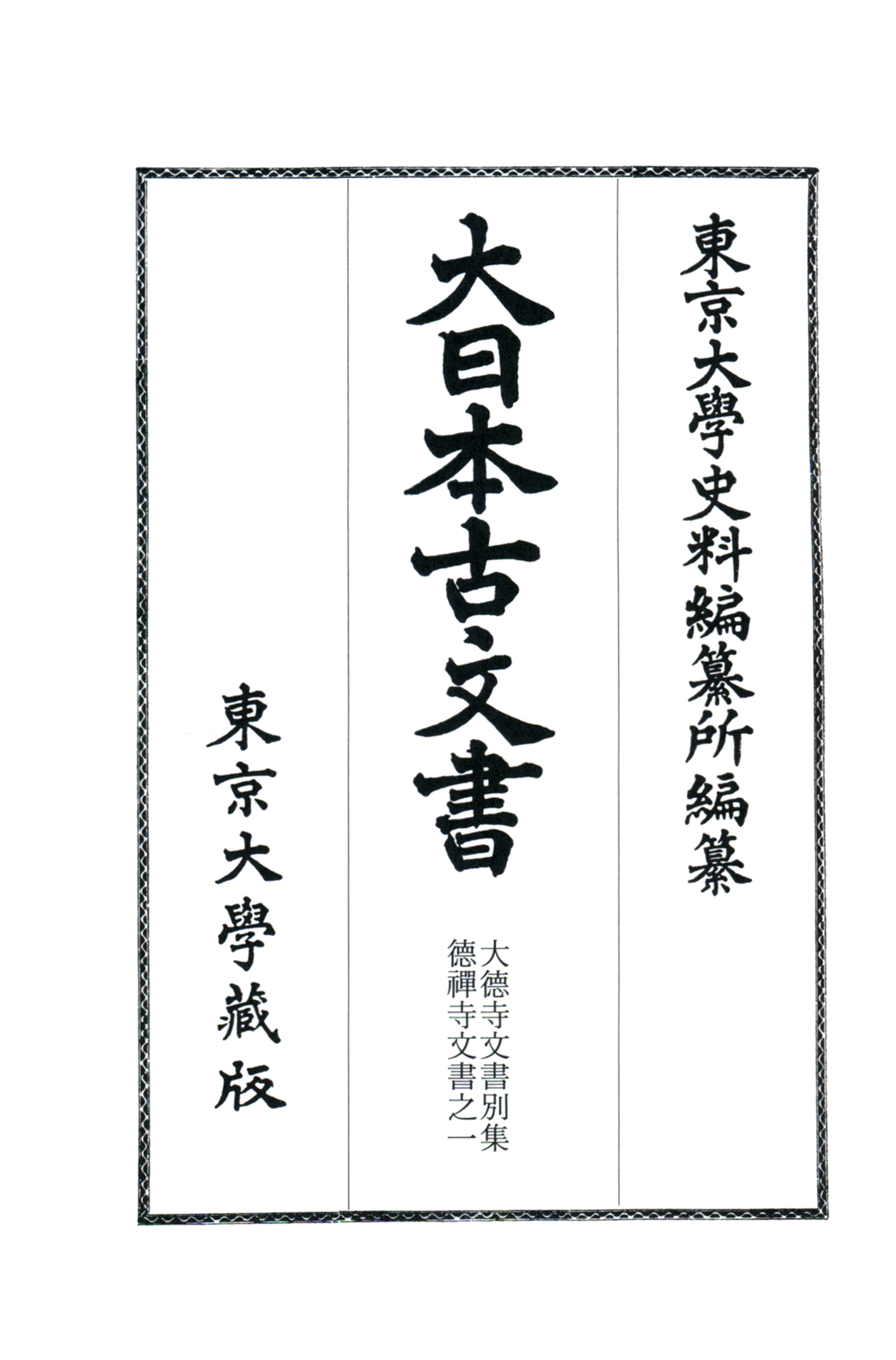

Dai-Nihon Komonjo Iewake dai 17, Daitoku-ji Monjo (Old Documents of Japan: Temple and Family Collections 17 - Daitokuji Documents, Separate Collections: Tokuzenji Documents 1)

Size

452 pages, A5 format

Language

Japanese

Released

April 24, 2020

ISBN

978-4-13-091266-2

Published by

University of Tokyo Press

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

The study of Japanese history makes advances through the analysis of historical sources, and among these historical sources old documents occupy an important position. Old Documents of Japan is a collection of basic historical sources that, since the publication of the first volume in 1901, has continued to be compiled and published by the Historiographical Institute at the University of Tokyo. “Compile” in this case means to transcribe in standard non-cursive characters the texts of documents that are often difficult for people today to read and were written chiefly with writing brushes, and to add notes about people’s names, place-names, and, as best as possible, the estimated date of the document if it is undated. Through the publication of these documents, the series Old Documents of Japan aims to make them available to people who wish to utilize them. The Daitokuji Documents, constituting the 17th collection among Temple and Family Collections of Old Documents of Japan, brings together old documents preserved at Daitokuji, a temple in Murasakino, Kyoto, founded by Sōhō Myōchō (a.k.a. Daitō Kokushi), a Zen monk of the Kamakura period. The present volume is the first volume in a separate collection of documents held by Tokuzenji, a sub-temple of Daitokuji founded by Sōhō Myōchō’s disciple Tettō Gikō.

The Tokuzenji documents have a major distinguishing feature, namely, that they are composed of two groups of documents whose character differs. That is to say, they consist of one group of documents made up of “ordinary” documents that have survived down to the present day because it was thought that they ought to be preserved and another group of documents made up of “discarded” documents that have by chance happened to survive down to the present day.

The group of discarded documents was found inside a sliding door. In 1984, repairs were made to a painting by Kanō Tan’yū on a sliding-door panel held by Tokuzenji, and a large number of old documents were discovered in the panel’s underlining. While some of these documents preserved their original form, most of them had been torn up. It is highly likely that they were deliberately torn up when the sliding door was made and were not merely torn up and disposed of. Be that as it may, this does not alter the fact that these documents were discarded during the Edo period when the sliding door was produced and were then reused when making the sliding door.

For this reason, the Tokuzenji documents differ from other groups of documents that have been intentionally preserved down to the present day, and one of their characteristics is that they include many everyday documents corresponding to present-day receipts, orders, invoices, and accounts books. It was in fact already known that documents discovered in the underlining of sliding-door panels include many such ledger-type documents, but in almost all cases the documents have been from the Edo period and later. In this respect, the documents found in the underlining of the sliding-door panel at Tokuzenji are quite unusual in that they include many documents of the medieval period, dating from as far back as the twelfth century, and documents that would normally have been preserved and have in fact been preserved elsewhere in the Daitokuji temple complex were used as underlining for a sliding-door panel.

These Tokuzenji documents are extremely interesting as a subject of analysis, but it is also true that they pose difficulties because of their use as underlining. Because they were torn up when being reused, many of the documents consist of fragments, and it is by no means an easy matter to decipher the information written on these fragments or to determine their dates, which is especially important when analyzing them. But overcoming such difficulties is one of the true joys of research. This publication cannot be described as a book for beginners, but nonetheless I would like people to thumb through it and take up the challenge of trying to analyze some of the documents.

(Written by KOSE Genshi, Assistant Professor, Historiographical Institute / 2021)

Find a book

Find a book