Title

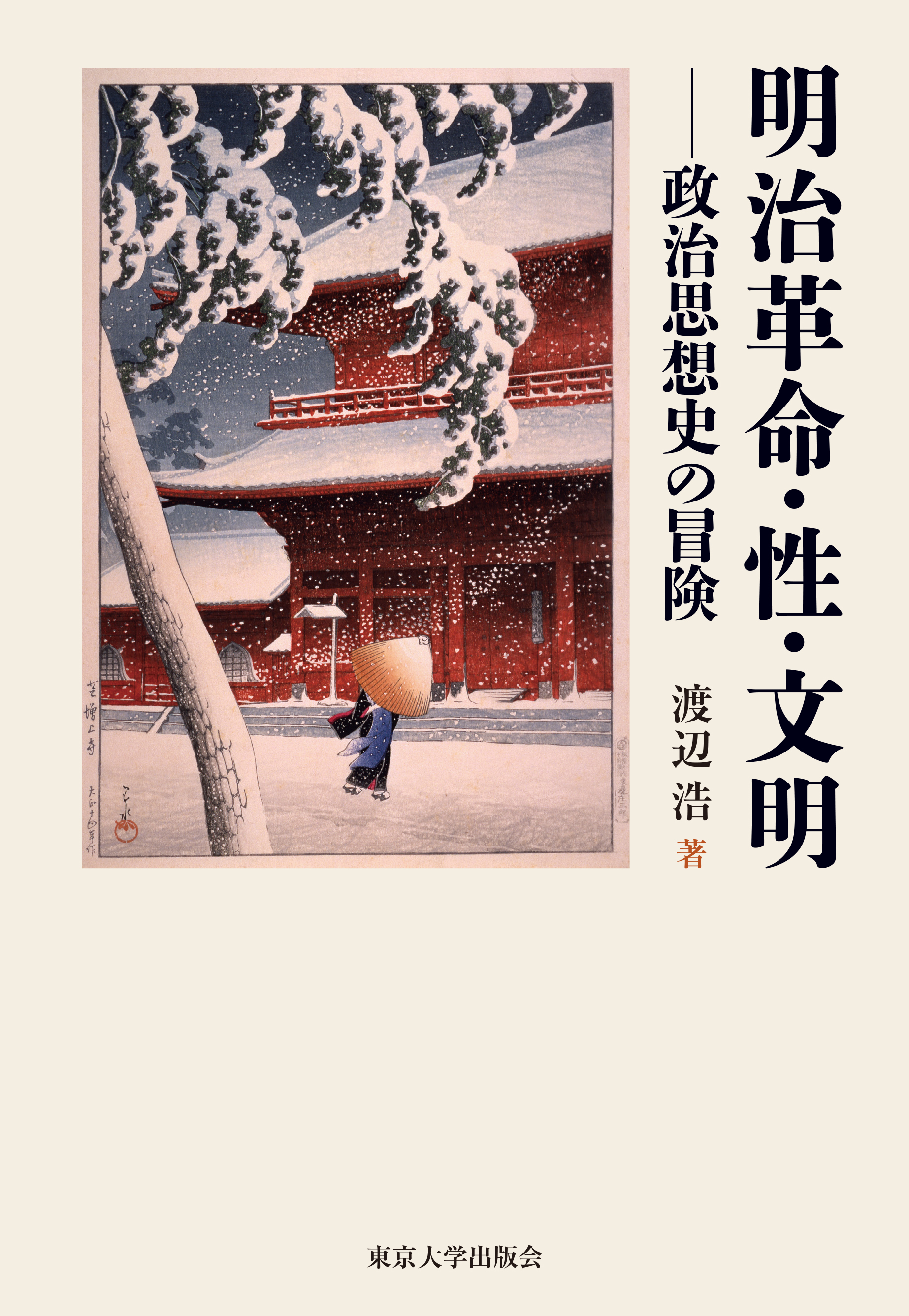

University of Tokyo Press 70th Anniversary Meiji Kakumei, Sei, Bunmei (The Meiji Revolution, Gender, and Civilization)

Size

640 pages, 127x188mm

Language

Japanese

Released

June 29, 2021

ISBN

978-4-13-030178-7

Published by

University of Tokyo Press

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

Q: What is this book about?

A: This book brings together essays that explore the history of Japanese political thought as it relates to several key themes, including revolution, gender, and understandings of “civilization” (bunmei). It mainly deals with the seventeenth through the nineteenth century, or in other words from the Tokugawa period through the Meiji Revolution (more commonly, but misleadingly, known as the Meiji Restoration) to the Meiji era. What ideas and feelings did Japanese of this time hold about politics in the broad sense of the term? How did this thinking change? Those are the questions that I try to answer. (For the purposes of this book, the word “Japanese” is used in the same way that it was in the Tokugawa period, namely to denote residents of the Japanese archipelago not including the peoples of the Ryukyu kingdom and the Ainu of present-day Hokkaido.)

Q: What is the significance of asking such questions?

A: To take just one example, it took fewer than fifteen years for the Tokugawa regime, which had endured stably for two and a half centuries, to collapse after Commodore Perry arrived with his tiny squadron. The new government that immediately replaced it then suddenly started to “civilize” Japan after the model of the West. How could such radical changes have taken place so swiftly? Because, of course, people acted in such a way. But why did they act in such a way? Because they held certain ideas and prospects about Japanese politics. In short, if you do not understand the political thinking that underpinned the actions of the people of the time, you cannot understand the Meiji Revolution.

Q: What does gender have to do with political thought?

A: Both the Tokugawa and Meiji governments consisted of only men. That means that gender was an important precondition of how these governments functioned and were organized. Surely it’s important to ask why.

Q: Isn’t it simply because that was what was natural at the time?

A: But why did people think that it was natural? Politics affects everyone, women as well as men. Yet in spite of that, people largely did not question why only men engaged in politics. There must have been reasons for that, and if you do not know those reasons, you will be failing to understand an important aspect of government during those centuries. People’s ideas concerning the “nature” and the ideal state of each sex made it possible for their governments to be the way that they were. That makes elucidating those ideas a crucial domain of research into political thought.

Q: But doesn’t all of that only have to do with the past, when the principle of equality between the sexes had not yet been established?

A: Is that really so true? Even in Japan today, most legislators, cabinet ministers, high-ranking bureaucrats, and judges of the Supreme Court are men. Every Japanese prime minister so far has been male. In terms of political empowerment Japan has one of the worst gender gaps in the entire world. Why? This is not a thing of the past. This is very much our own problem.

Q: What is bunmei, and what is its significance to Japanese political thought?

A: Many of my readers will already be familiar with bunmei kaika, the slogan that was used in Meiji Japan to encourage rapid westernization. Bunmei derives from an old Confucian word (wenming) indicating a state in which people are prosperous and highly moral. In Japan in the late nineteenth century the word was adopted as a translation of “civilization,” a concept much beloved of Westerners of the time. In effect, the old Confucian ideal and the new Western ideal merged in this term bunmei to turn it into a fashionable and prestigious catchphrase that nobody could easily deny. But in fact, the task of “civilizing” Japan involved many difficult quandaries and attempts at answers. What was “civilization”? Which policy was more “civilized” compared with others? My discussion introduces some of these debates, which drew not only on Western sources (as is often commonly assumed) but also on longstanding Confucian ideas for inspiration.

I would be pleased if my examination of Japanese political thought according to these themes helps readers see “Japanese history” in a new light.

(Written by WATANABE Hiroshi, Professor Emeritus, Graduate Schools for Law and Politics / 2021)

Find a book

Find a book

eBook

eBook