Title

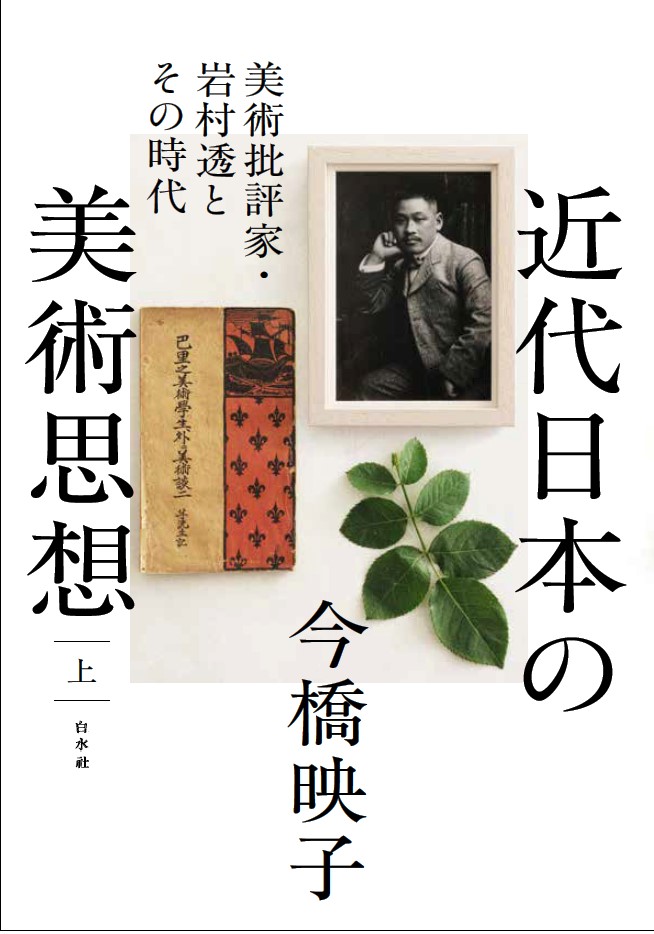

vol.1 + vol.2 Kindai-Nihon no Bijutsu-Shiso (Artistic Thought in Modern Japan - Art critic Toru Iwamura and his era)

Size

(vol.1) 716 pages, A5 format (vol.2) 788 pages, A5 format

Language

Japanese

Released

ISBN

(vol.1) 9784560098189

(vol.2) 9784560098196

Published by

Hakusuisha Publishing

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Kindai-Nihon no Bijutsu-Shiso (vol.1) Kindai-Nihon no Bijutsu-Shiso (vol.2)

Japanese Page

Picking up a beautifully bound book at a bookstore, spending a leisurely day going to see an exhibit at an art museum and stopping afterwards in a café, buying local handicrafts on a vacation, or strolling around a park built around the remains of structures from the Edo period—these are all recreational activities and customs that have become a natural part of our everyday lives. But what would you think if you found out that these were the fruit of efforts by pioneers less than a hundred years ago?

The book, titled Artistic Thought in Modern Japan: Art critic Toru Iwamura and his era, examines the period from 1900 to 1917 at which point full-fledged education in Western painting had just started in Japan. During this era, Western-style painters had not yet established a place in the art world, and the so-called “avant-garde” movement that radicalized art had not yet occurred. The book digs into the unknown history of this era to shine a light on the struggles of individuals who helped to greatly broaden the concept of “art” and not only encouraged young artists but also worked to protect the artists’ financial independence and legal freedom. Although the term “artistic thought” in the book’s title may be unfamiliar to Japanese readers, as in the case of “Buddhist thought” and “economic thought,” it refers to the systematic effort (rather than uncoordinated attempts) to understand the phenomenon of “art” and to discuss how society should support this “art.”

As a way to delve deeply into the artistic thought of this era, the book focuses on a single art critic, Toru Iwamura (1870-1917). Toru Iwamura was the first-ever professor of Western art history at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts who, along with Seiki Kuroda and Keiichiro Kume, were called the “Art-school Triumvirate.” In contrast to Kuroda who is referred to as the “master” of the modern art world and is well-known even today because of his frequent mention in textbooks, Iwamura is largely unknown. That said, Iwamura was an exceptionally talented art historian and critic who is said to have possessed near-native English ability as well as broad knowledge and research skill regarding not only art but the humanities as a whole. Above all else, he is said to have been a forthright critic who did not pull any punches.

The author believes that Iwamura’s artistic thought was, more than anything else, rooted in his recognition of the need for a “100-year resolve for art” similar to the “100-year plan for the nation.” Around the year 1900, there was not a single “art museum” in Tokyo where artists could exhibit new works or learn about the latest trends in foreign art (as opposed to a museum where old artifacts are exhibited). Nor were there any galleries where independent artists could show their art or cafés where artists could get together to discuss their work. There were no magazines or other media where information about foreign art could be easily obtained, much less opportunities to actually see Western painting and Western sculpture. Nude paintings and nude sculptures would immediately catch the eye of the authorities and be subjected to restriction. The very status of being an “artist,” “sculptor,” or “architect” had not yet been established in society. Finding themselves in an emerging city in Asia devoid of absolutely everything, Iwamura and his colleagues set about creating a “100-year plan for art.” At the core of this endeavor was, undoubtedly, the same type “resolve” that was at the core of the civic rights and freedom movement.

The book comprises two volumes with over 1100 pages and represents the culmination of 30 years of research by the author. Although it perhaps cannot be read in its entirety at one sitting given its length, the book presents the intersecting dramas of various individuals and sheds light on the earnest struggles of Toru Iwamura and his colleagues, their hopes and setbacks, and their message to and prescience regarding Japan a hundred years in the future.

Are literature and art really “nonessential and nonurgent” as some suggest? That is a question that I would like young readers to ponder as they read this book.

(Written by IMAHASHI Eiko, Professor, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences / 2021)

Related Info

The 12nd Nihon-gaku Award (Nihon-gaku foundation Nov 3, 2024)

https://nihongaku.jp/news/archives/3

Find a book

Find a book