Title

Chusei-Zenshu no Jugaku-Gakushu to Kagaku-Chishiki (Confucian Learning and Scientific Knowledge of Zen Monks in Medieval Japan)

Size

320 pages, A5 format, hardcover

Language

Japanese

Released

February, 2021

ISBN

978-4-7842-2000-7

Published by

Shibunkaku

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

One tends to think of Zen monks as meditating somewhere deep in the mountains. This is, of course, true, but this was not all that they did in the Muromachi period. They also painted Buddhist statues, arranged rocks in landscaped gardens, went to their temple’s landed estates to collect the annual land tax, and engaged in money-lending operations together with professional money-lenders. They did not confine themselves to sitting quietly in meditation, and also did all sorts of other things in various places.

Monks who engaged in such activities outside doctrinal studies were called tōban monks. Although they did work related to the management of their temple which may at first glance seem to have been unrelated to Zen, these monks were deemed to be on an equal footing with seiban monks, who engaged in scholarship. In Zen monasteries, the work of tōban monks formed part of their cultivated practice, just like the studies of seiban monks.

The activities of tōban monks were to have an enormous influence on Muromachi society and culture. The operations of landed estates and money-lending sustained the finances of the Muromachi shogunate, while the supervision of Buddhist statues and temple gardens led to the production of works of art and the golden age of ink painting. Why, then, were tōban monks able to undertake such varied activities? And how did they acquire the necessary skills and knowledge? The aim of this book is to answer these questions.

I pay particular attention to the lectures held at Zen monasteries. During the medieval period, lectures were given at Zen monasteries not only on Buddhist texts but also on Chinese works such as the Analects of Confucius (Lunyu), the Book of Changes (Zhouyi), and Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji), and both seiban and tōban monks eagerly attended these lectures. By perusing the monks’ notes on these lectures (called shōmono), one can gain a vivid idea of lectures at the time.

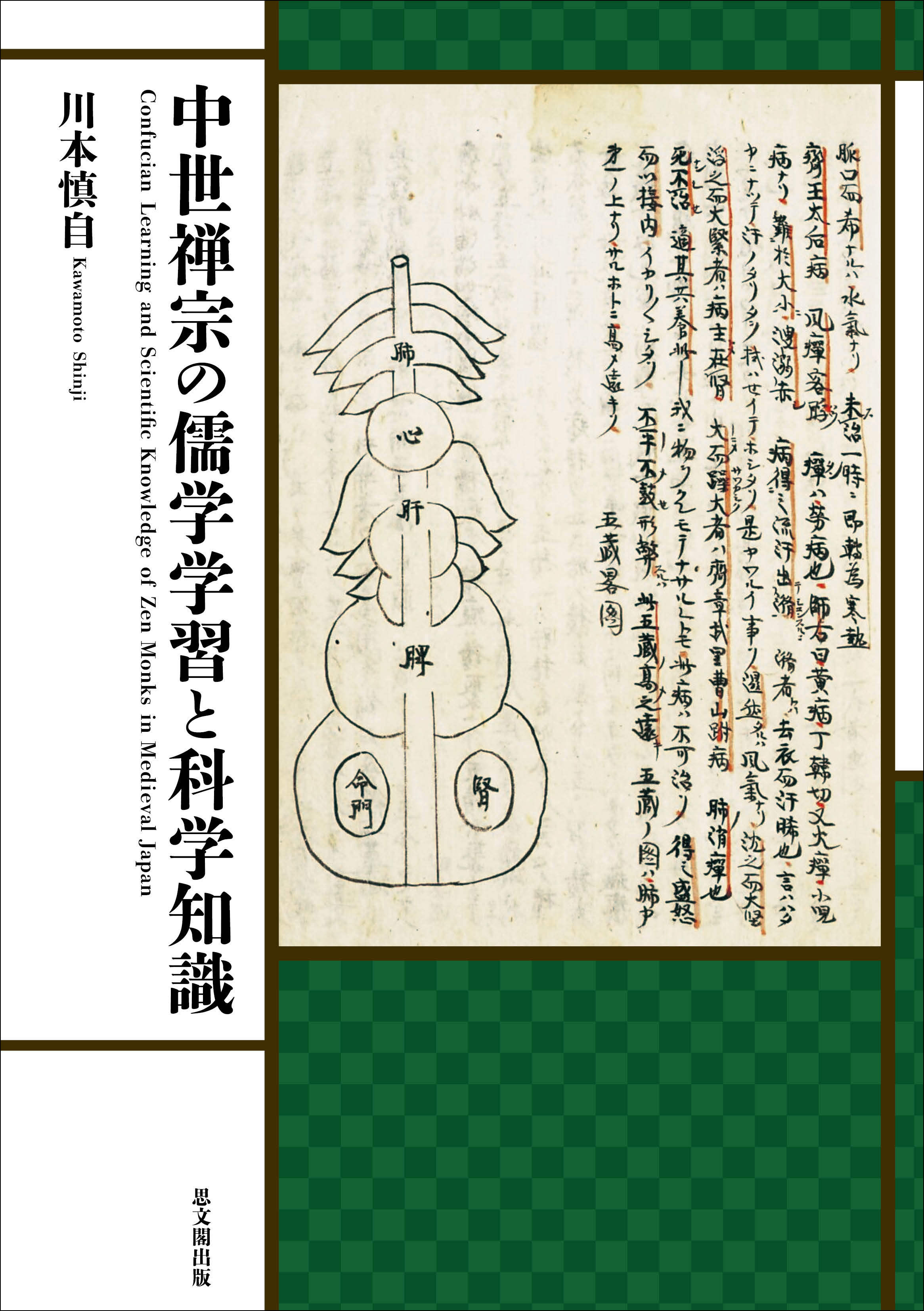

For example, in lectures on the biographies of physicians in Records of the Grand Historian medical treatments and their methods were explained in detail together with diagrams showing the positions of the five viscera and six bowels. In lectures on Du Fu’s poems, the explanation of a poem about a pastoral scene touched on districts where red rice was produced and on paddy fields on the shores of Lake Biwa. In lectures on the Book of Changes, the rudiments of making calculations by using divining rods were carefully explained as a precondition for divination based on the Book of Changes.

When considered from the perspective of explications of Chinese texts, such lectures were no more than digressions and small talk, but for the Zen monks attending them they provided living, practical knowledge. Knowledge of agricultural conditions in different regions and methods of reckoning were indispensable for managing temple landholdings, and they were also helpful for producing art works, erecting buildings, and landscape gardening. It goes without saying that basic knowledge of medicine was useful in everyday life, and in later times Zen monasteries did in fact produce many physicians.

Lectures on Chinese works, which from today’s vantage point would seem to belong to a world at the furthest remove from practical utility, were brimming with knowledge that was of practical use to medieval Zen monks. I hope that this book will enable the reader to realize this.

(Written by KAWAMOTO Shinji, Associate Professor, Historiographical Institute / 2021)

Find a book

Find a book