Title

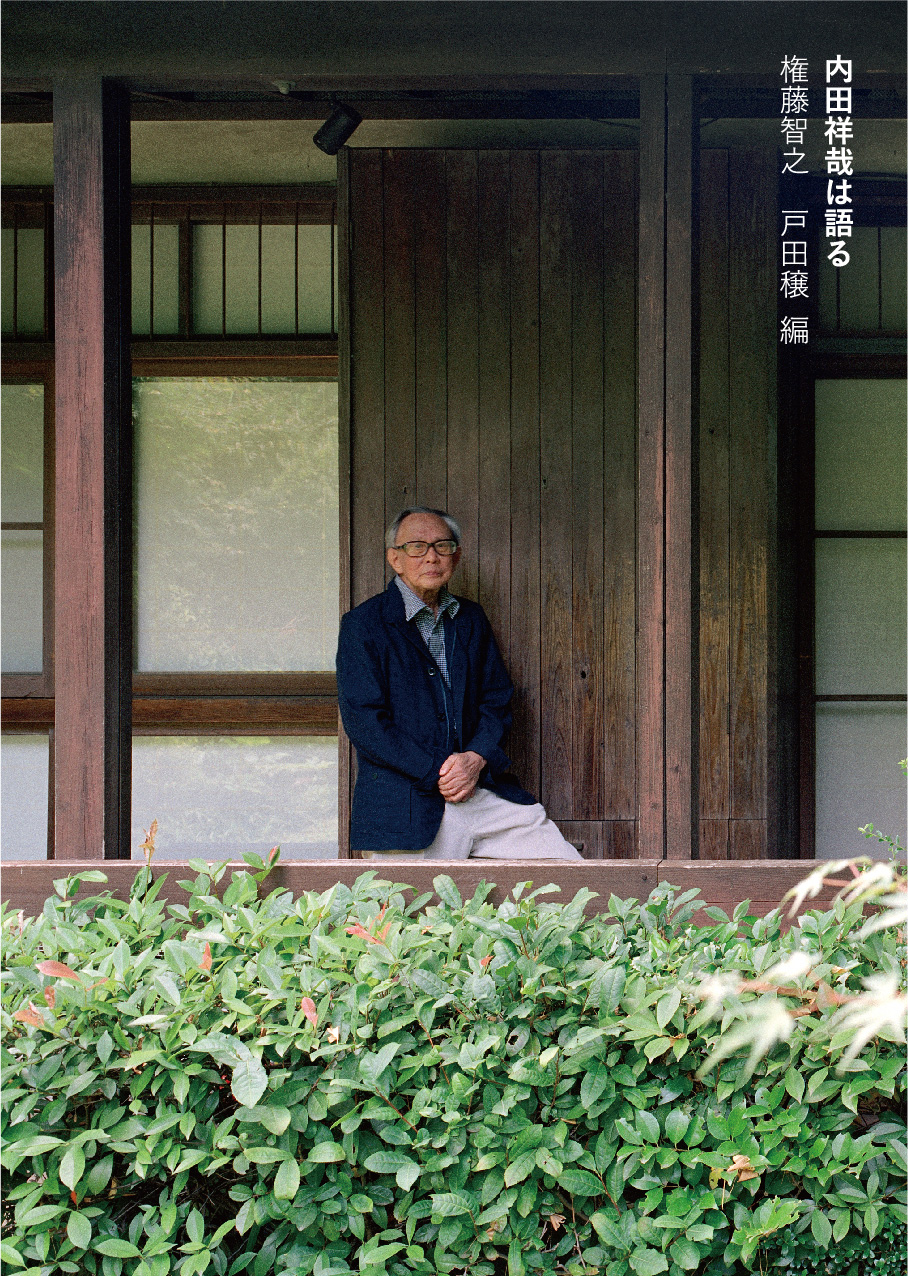

Utida Yoshichika wa kataru (Yoshichika Utida Speaks)

Size

328 pages, A5 format

Language

Japanese

Released

March, 2022

ISBN

9784306046917

Published by

Kajima Publishing

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

Although it may depend on the definition, the department of architecture appears to be the only department in the school of engineering with a laboratory devoted to the history of the discipline. I myself graduated from a department of architecture, and I know many successful architects who completed an architectural history laboratory. Yoshichika Utida (a professor emeritus of Department of Architecture), the subject of this book, went so far as to say that history should form part of the engineering curriculum. Why is history so important in engineering? The reason is that the history of addressing social needs offers many insights for the future direction of engineering.

Yoshichika Utida lived through the drastic changes of postwar Japan and continually produced architectural solutions for the country’s problems. This book reveals the life of Utida through some twenty interviews with the architect. The interviews were conducted by Jo Toda, an architectural historian, and by Tomoyuki Gondo, a researcher of building systems, in which Utida himself specialized. Two interviewers were required because of Utida’s wide-ranging achievements, which spanned from architectural design to building systems. Utida is among the few architects to have earned the Prize of the Architectural Institute of Japan for both architectural works and research.

Yoshichika Utida was born in 1925 in Tokyo. His father, Yoshikazu, designed many of the buildings on the campus of the University of Tokyo and was the university’s president (1943–1945) at the end of the Second World War. Yoshichika graduated from the University of Tokyo after the war and joined the Ministry of Communications (a no-longer-extant ministry like the one that combined the current post office and the Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Public Corporation). Amid the postwar demand for mass construction, those who were only in their twenties were tasked with designing large buildings. Yoshichika designed telegraph stations, telephone stations, and related facilities to be built across the nation; for these designs, he consulted architectural literature from overseas and incorporated new structural elements such as steel-reinforced domes and glass-block walls. In 1956, Yoshichika became an assistant professor at the University of Tokyo, marking the start of his career as a teacher/researcher of building systems. This discipline was designed to evaluate the functionality/performance of architectural methods, which had dramatically changed in the postwar years, and the insights were applied in the development of new architectural technologies such as prefab housing and high-rises. Alongside his research work, Yoshichika designed public buildings for areas far beyond Tokyo, incorporating modernist designs and acrobatic structures. Examples include the Saga Prefectural Library and the Saga Prefectural Art Museum, the latter of which won the Prize of the Architectural Institute of Japan. The Japanese architectural scene underwent a major transformation in the 1970s and 1980s. Whereas steel-reinforced concrete had played a key role in easing Japan’s housing shortage, people were now beginning to question whether it was really as durable as was thought (the idea that such material would last forever seems inconceivable today, when we see around us many dilapidated concrete structures). Utida himself started researching such themes as extending building lifespans and reviving the country’s traditional wooden architecture. These themes feature in his actual designs too. Next 21 (stylized NEXT21) and other buildings with extended lifespans garnered international attention.

Thus, in Yoshichika Utida’s life, we can trace the development of postwar Japanese architecture. Utida was an engineer insofar as he responded with acute sensitivity to the dramatic changes of the times and in social needs, but in the buildings and furniture he designed, and in his writings, you can find sublime and intriguing content. This book, complete with numerous illustrations and photos, is heartily recommended. Frankly, it may have little appeal to those with no interest in architecture. However, if you have even the slightest interest in architecture, you will surely find something engaging within.

(Written by GONDO Tomoyuki, Associate Professor, School of Engineering / 2022)

Find a book

Find a book