Title

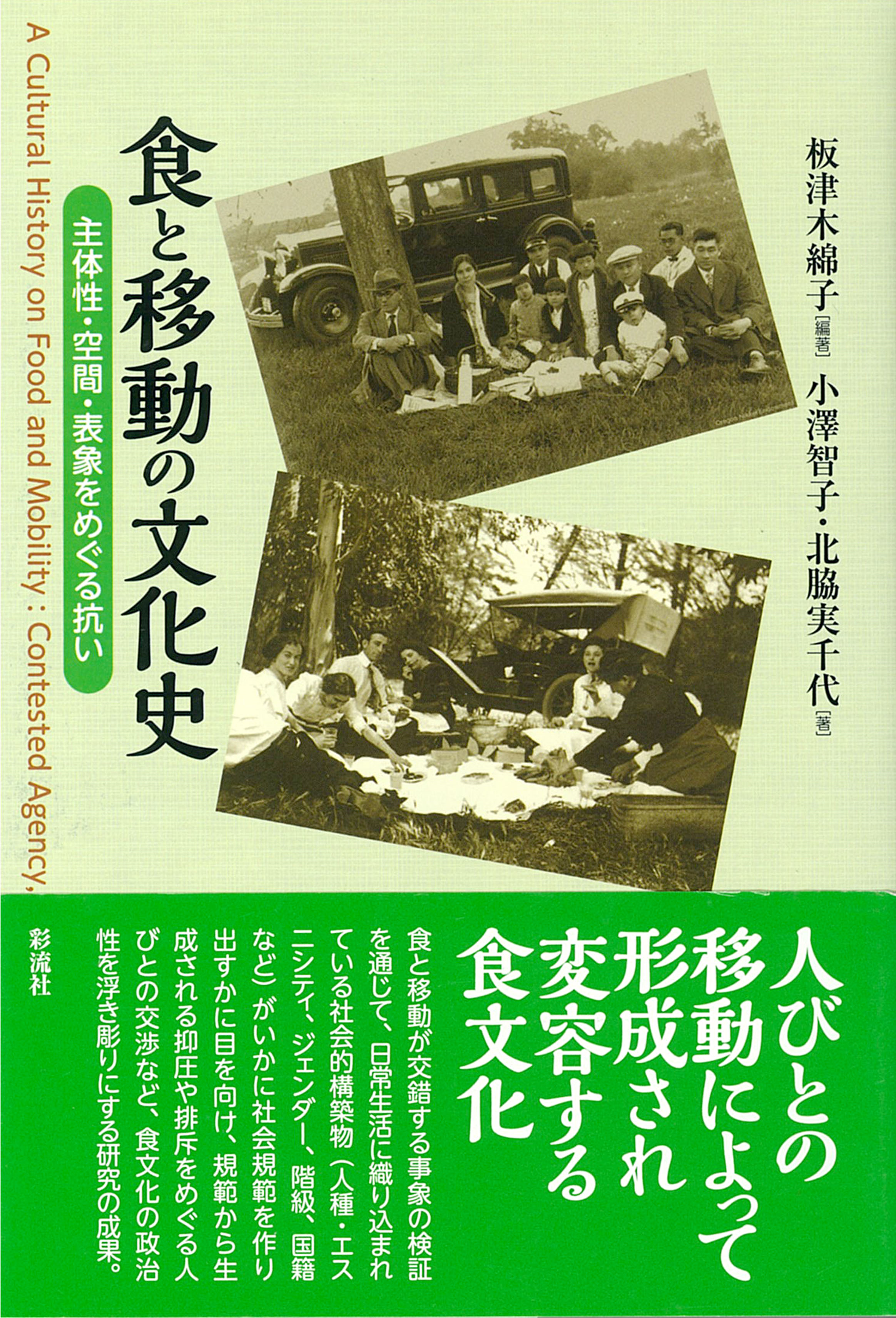

Shoku to ido no bunka shi (A cultural history on food and mobility - Contested agency, space and representation)

Size

316 pages, 127x188mm

Language

Japanese

Released

February 26, 2021

ISBN

9784779126642

Published by

Sairyusha

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

We are able to enjoy a vast range of food without leaving Japan. As if to underline this fact, Japan imports 62 percent of the food it consumes from abroad. It is surprising that even when people’s movements were restricted due to the COVID-19 crisis, the food on our dining tables did not change much. No shortages of Philippine bananas, French cheese, or Brazilian coffee beans were experienced. The only food shortage related news that surfaced was that, at one point, a fast-food chain had stopped selling potato fries due to a shortage of potatoes from the United States. Our food culture changes and becomes enriched by the movement of people and goods, leading us to encounter new tastes which we bring home. Additionally, immigrants transform their dishes in Japan to adapt to new local food sources.

A Cultural History of Food and Mobility: Contested Agency, Space, and Representation examines the agency of people in relation to food and mobility from the perspective of cultural history. The French sociologist Henri Lefebvre argues in his La production de l’espace that “space is socially constructed.” Using a case study of the everyday food life of people living on the Pacific Rim from the nineteenth to the first half of the twentieth centuries, this volume examines the kind of socio-economic structure reflected in the space surrounding food and how that space served as a focal point to mount resistance to existing hegemonic powers.

The volume’s main feature is its attempt to depart from a historical perspective that takes the existence of the state and borders for granted in examining the history of food. Conventional food research has been carried out using a historical perspective based on national borders, as seen in the history of Japanese, Italian, and Korean cooking. Research into national histories of food tends to label activities surrounding food within the confines of an authentic or inauthentic binary. However, trying out new food ingredients from a different culture in one’s everyday cooking does not have to be looked down upon as inauthentic. Neither should these activities be controlled by the state. The current volume has endeavored to write a history of quotidian food practice with its focus on the Everyman.

For example, there was a Japanese tea boom in North America during the Meiji era that necessitated the re-processing of processed tea so that it could survive transpacific transport by ship and land. Tomoko Ozawa investigated the working conditions of women in these tea factories in foreign settlements, and how Japanese tea was consumed by white women in North America. Michiyo Kitawaki examined how second-generation Japanese American women learned Japanese cooking in America, and the kinds of cultural negotiation it signified regarding gender and social norms. Ozawa also examined cookbooks written by second-generation Japanese American women as a graduation project to determine how individuals born and raised in America represented Japanese cooking while they were studying in Japan. Kitawaki used oral history to investigate how migrants interacted with each other through food at a sugar cane plantation in Hawaii. Furthermore, Yuko Itatsu focused on the practice of picnics in Los Angeles in the 1920s. Using photographs and newspaper articles, she described the process through which picnicking, which seems to be an everyday triviality, became an important symbolic activity in Southern Californian culture, particularly as midwestern populations vied for hegemony.

(Written by ITATSU Yuko, Professor, Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies / 2023)

Find a book

Find a book

eBook

eBook