Title

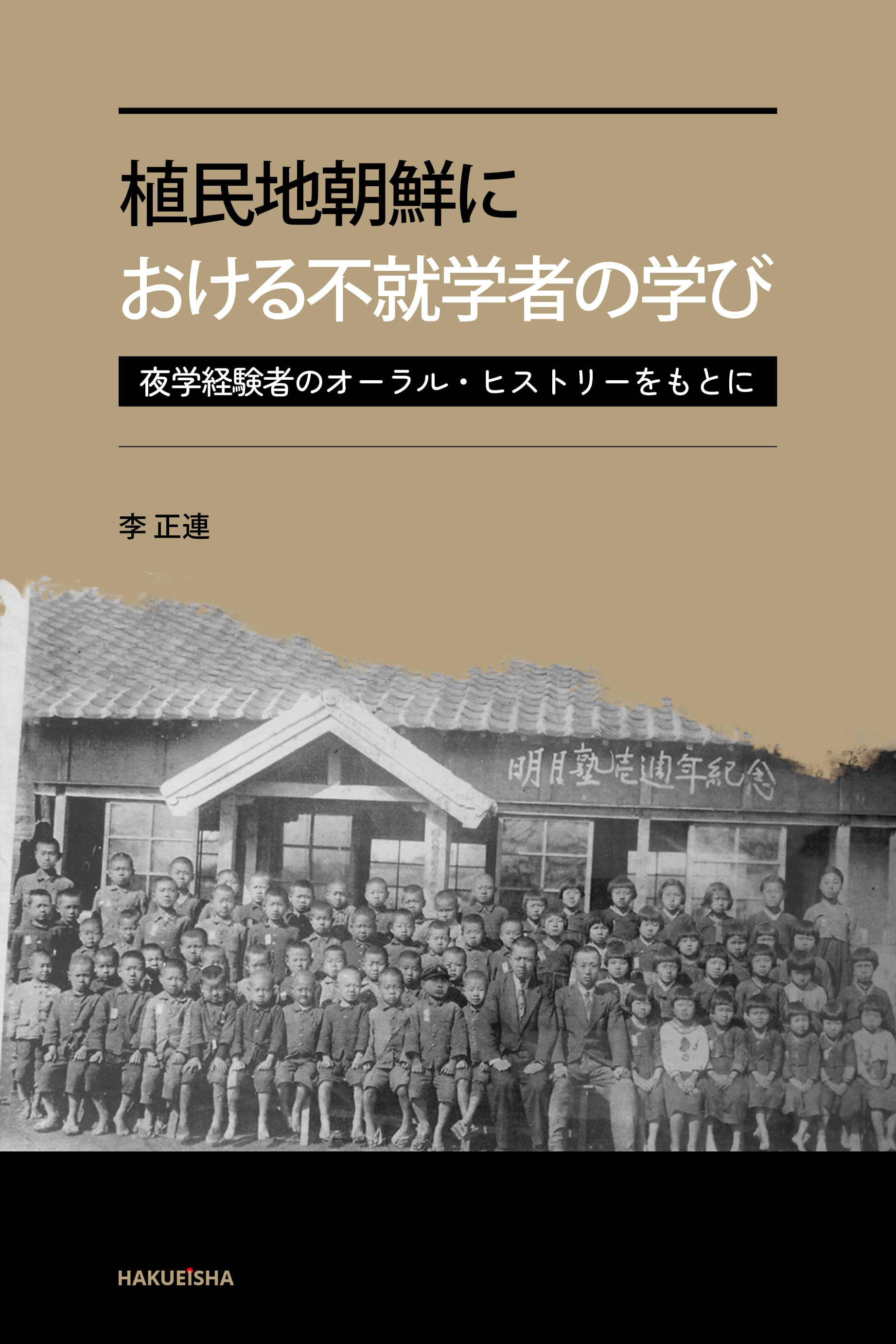

Shokuminchi-Chosen ni okeru Fushugakusha no Manabi (How School Non-attendees Studied in Colonial Korea - On the Basis of Oral Histories of Night School Students and Instructors)

Size

373 pages, A5 format

Language

Japanese

Released

March 01, 2022

ISBN

9784910132211

Published by

HAKUEISHA

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

This book, based on the life histories of people who studied or taught at night school, clarifies the realities of learning for school non-attendees in colonial Korea and also examines the role played by night schools at the time and their significance.

Following the March 1st independence movement in 1919, the education fever of the Korean people in colonial Korea grew steadily. But the establishment of additional schools by the Government-General of Korea was unable to keep up with the ever-growing education fever of Koreans, and competition for enrolment in both elementary and secondary schools continued until the end of colonial rule. In other words, the percentage of school-age children attending school in colonial Korea remained low during the thirty-five years of Japanese colonial rule, and even towards the end of colonial rule it was only about fifty percent. The prime reason for this could be said to have been the Government-General’s lukewarm response to the issue of school non-attendance.

Educational facilities that supported the learning of children unable to attend school included night schools, training schools, and private schools found throughout Korea. These educational facilities provided an education not only for children unable to attend school but also for youths past school age, farmers, workers, and women. While some of these educational facilities and educational activities were provided by the authorities, most of them were provided by Koreans themselves. In short, the desire of the Korean people for a modern education was not fulfilled by the schools provided by the Government-General, and the people themselves established and operated night schools and training schools and studied there.

Past research on this educational praxis of the Korean people, that is, on night schools, has mostly been founded on the binary perspective of “oppression versus resistance,” and a perspective that would understand these educational facilities as places for the ethnic education of the Korean people has predominated. But from such a perspective the Korean people can be depicted primarily only as targets of “oppression” or agents of “resistance,” and their aspect as subjective agents in daily life and education who protected and built up their lives and learning is overlooked. In order to overcome this binary perspective and in order to supplement the evidentiality that has been lacking in research on night schools in colonial Korea by taking into account issues in past research on night schools that has relied only on written sources, this book brings together and examines the testimonies of people who actually studied or taught at night schools at the time.

Finding people who had experience of night schools at the time was by no means easy. When I began my investigations in 2013, such people were already over eighty years old, and because, unlike ordinary schools, almost no records such as school registers have survived for night schools, it was extremely difficult just to locate people with experience of night schools. Nonetheless, during about five and a half years from April 2013 to October 2018 I was able to locate a great many such people and hear the life histories of sixty-four of them (sixty students and four instructors).

According to the testimonies of these people, the Korean people during the colonial period were subjective agents who actively obtained an education or else created their own forms of learning in order to improve their living circumstances, rise in social status, or enjoy new forms of culture. When night schools are understood from the perspective of people who studied there, there are many aspects that cannot be explained by the past schema of “oppression versus resistance.” The night schools that the people established themselves in the midst of a poor educational environment became places that accepted children, youths, women, and so on who were not attending school, and at the same time they also played a role in cultural exchange among local inhabitants and served as community centres.

(Written by Lee Jeongyun,, Professor, Graduate School of Education / 2022)

Find a book

Find a book