Title

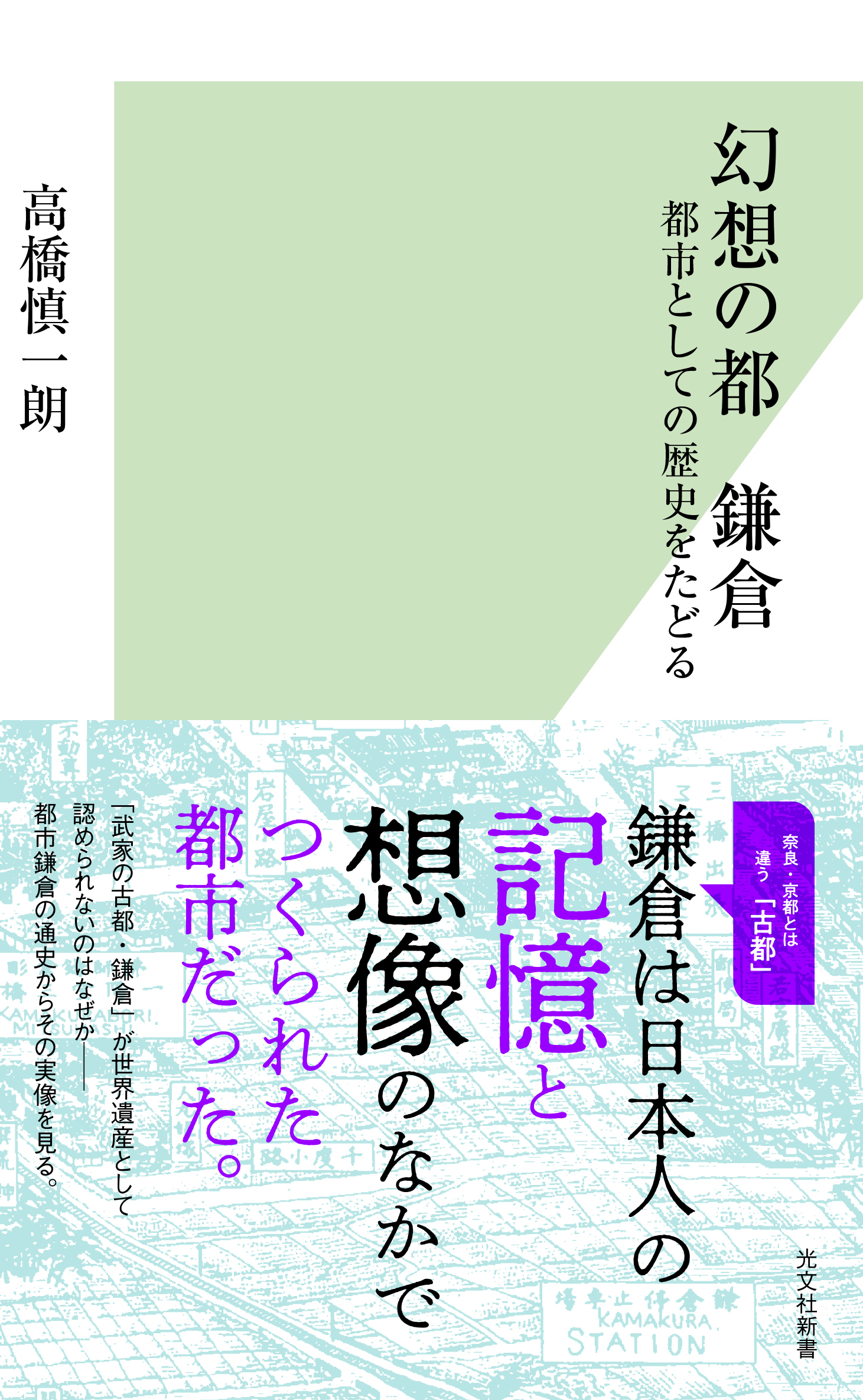

Kobunsha Shinsho Genso no Miyako, Kamakura (Kamakura, an Illusory Capital - Tracing Its History as a City)

Size

198 pages, paperback pocket edition

Language

Japanese

Released

May 18, 2020

ISBN

978-4-334-04607-1

Published by

Kobunsha

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

Kamakura is a strange “former capital” of Japan. It is a small city with a population of about 170,000, but it is one of the main tourist sites in the Greater Tokyo Area, being visited by about twenty million tourists annually. Visitors to Kamakura are attracted by the atmosphere of a former capital that gives a vague sense of the weight of history and by its appearance, which is difficult to define. But today there are almost no structures in Kamakura that go back to the Kamakura period, and many of the buildings and much of the scenery that people feel to be evocative of a “former capital” date from modern times. Why, then, is Kamakura endowed with the appearance of a “former capital”? The aim of this book is to clarify how the appearance of the “former capital” of Kamakura evolved by tracing the history of the city of Kamakura from the Palaeolithic period down to the present day.

Chapter 1 traces the history of Kamakura from the Palaeolithic period to the first part of the Kamakura period. Ever since people first appeared in Kamakura twenty thousand years ago, settlements gradually formed, chiefly in its current outlying areas. District offices were established here in the Nara period, and many people began to live in its environs, as a result of which Kamakura became a city. And with the establishment of the shogunate by Minamoto no Yoritomo Kamakura became a “warrior capital.”

Chapter 2 deals with Kamakura’s history from the middle of the Kamakura period to the latter part of the Muromachi period. The Hōjō family, who took effective control of the Kamakura shogunate, improved Kamakura’s infrastructure, starting with its roads, and warriors proceeded to open up the valleys. Even after the fall of the Kamakura shogunate, the Muromachi shogunate and warriors of the Sengoku period continued to attach importance to Kamakura, considering it to symbolize the fact that it was the rulers of Kamakura who were the legitimate rulers of the Kantō region.

Chapter 3 examines the early modern period. In the early modern period, the shogunate was located in Edo, and Kamakura was no longer a political center. Instead, it became a tourist town, and new oral traditions about historical events of the Kamakura period were also born. Kabuki and ukiyoe set in medieval Kamakura were another factor that drew tourists to Kamakura.

Chapter 4 deals with the period from modern times to the present day. From the Meiji era onwards, Kamakura became a health resort blessed with many historical sites, large numbers of villas and luxurious residences were built, and many writers, attracted by images of the Kamakura period, took up residence in Kamakura. And while it is a fashionable seaside tourist resort, its appearance as a quiet, retro town took root.

On the basis of the above, this book shows that the “former capital” Kamakura that we recognize today is not the former capital as it existed during the Kamakura period, but is a grand assemblage of legends and attractions—or “illusions”—to which people fascinated by the former capital have added down through the ages. Information about historical figures and events since ancient times is embedded in place-names and oral traditions in Kamakura, and vestiges of the activities of people who have loved the former capital of Kamakura down to the present day have accumulated over time. I conclude that fragments of such various memories have intermingled to shape the appearance of a “former capital.”

(Written by TAKAHASHI Shinichirou, Professor, Historiographical Institute / 2022)

Find a book

Find a book