Jamma Masjid, the largest mosque in Delhi. © Hiroshi Marui.

Approximately 30 years ago I spent two years studying in India. During my daily routine and also on holidays throughout India I always felt that time seemed to flow at a leisurely pace. Once, while on a bus journey, I recall even now the tremendous, yet inexplicable sense of release I felt as I relieved myself at the dawning of a new day as I gazed out across the plains of India and their wide open skies and expansive earth. It is certainly the case that India covers territory ten times the size of Japan, and has an incredibly long history. It is estimated that the ancient scriptures know as Vedas were compiled approximately 1,200 years before the Christian era. But is it only this size and the length of India's history that seems to impact the flow of time? Whatever the case, in this article I would like to explore a little about how Indian philosophy or religion (the two are difficult to separate from each other), including Buddhism, perceive time.

Scene from a Sikh festival in Delhi's old city. © Hiroshi Marui.

What is particularly characteristic of Indian philosophy and religion is that unlike Judaism and Christianity, it does not perceive time in a linear sense, starting with the creation of the world by god and moving through history towards eventual Armageddon. Instead, Indian philosophy and religion perceive the universe in terms of the eternal repetition of birth, life and death, in a cyclical and recursive concept of time in which all life is constantly being reborn from an infinite past in a process of reincarnation. In addition, the time scale for this process is truly epic in nature, with one human year being equivalent to one day for a Hindu god, or Deva. Accordingly, the four epochs of the universe, known as Yuga, which represent a process of decline and degeneration, combine to form one Maha Yuga (we are currently in the final and worst epoch, known as Kali Yuga), with one Maha Yuga spanning 12,000 Deva years (4,320,000 human years). A total of 1,000 Maha Yuga is known as a Kalpa (4.32 billion human years). However a Kalpa represents only one day (only the day time and not the night time) for Brahma, the god of creation. The annihilation of the universe will occur at the end of the daylight hours of a day in the life of Brahma. The universe will then be consumed by fire and dissolve into a great sea. Brahma then sleeps for an entire night on the back of a great serpent and when the dawn comes the cycle begins once more with the creation of the universe.

At the home of Professor Sukla, a researcher of logic in India. © Hiroshi Marui.

Furthermore, in Indian thought, in which there is a strong tendency to hypostatize all things, although in answer to the question "What is the ultimate cause of the world?" various views have been propounded, including that the ultimate cause is god, or the atom, or the processes of the natural world, there have also been philosophies that suggest that the reality of time is the ultimate cause that controls the formation of and changes in all living things. However, in a reality that is permanent and eternal those thinkers who accept the presence of an omnipotent god believe that such a god would not be subject to the rule of time. Rather it is the case that they believe that time, which governs the beginning and the end of the world and the birth and death of all living things is under the control of god and therefore the word Kaala, which equates with time, gains a sense of meaning as "death." In the Vaisheshika school of philosophy, which analyzes the world and all events pluralistically and mechanistically in terms of nine substances, time is nothing more than one of these substances, on the same level as the soul, elements and space. However, only transient substances (those that can be perceived by the senses) are subject to the control of time, and eternal substances such as the soul, ether and space are beyond the control of time.

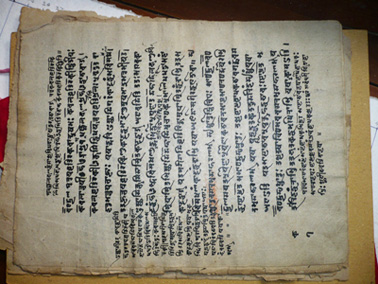

Copy of the ancient Sanskrit sources of Indian philosophy. © Hiroshi Marui.

On the other hand, in Buddhism, which teaches the impermanence of all living things, the predominant tendency is to perceive things not as fixed or in terms of substances, but rather as ever-changing, ephemeral phenomena. Buddhism therefore clearly recognizes the truth that all living things must die and moves away from fixed or otherwise constrained views, seeking to achieve enlightenment from the fickle hand of reality and to reach a state of nirvana. The Buddha is none other than the one who has awakened to this truth, or Dharma. So what happened to the Buddha, who had awakened to Dharma, after his death? In response to such a metaphysical question, which transcends our own experiences of whether the world is finite or infinite in terms of time and space, if we look at the "neutral" countenance of the Buddha, who remains mute, given that there is no meaning in seeking to answer such questions, we could perhaps get a sense that it is pointless to seek to understand what happened to the Buddha after death in terms of life and death or existence and non-existence.

Busy streets on the way to Jamma Masjid. © Hiroshi Marui.

However, in Mahayana Buddhism the nature of the Buddha changes significantly. In the Lotus Sutra a concept appears that treats the Buddha as eternal. Similarly, in Jodo (Pure Land) scriptures the Amitabha Buddha is ascribed as possessing infinite light and infinite life. This represents the emergence of a Buddha who possesses a nature as an absolute god, transcending time. Another notable feature of the Lotus Sutra is the epic timescale of its narrative. It is said that Amitabha was a monk known as Dharmakala in a previous life, who, before setting out to save all life, spent the incomprehensibly long period of five Kalpas in contemplation. For example, according to one Kalpa analogy it is stated that if a rock mountain with a base measuring 1 yojana (7km) in circumference were to be wiped with a soft cloth once every hundred years and this practice was repeated until the mountain had been rubbed away, the Kalpa would still not be at an end. In a similar way to the concept of Yuga in Hinduism, we also see in Buddhism a perception of history as a process of decline and degeneration (we are currently in the worst epoch, known as the latter days).

Against this virtually incomprehensibly vast recursive Kalpa timescale, the life of a single human being is probably nothing more than a fleeting dream, or a single drop of water in a huge ocean. The philosophers and holy men of ancient India preached that the endless cycle of life and death that has continued since the remote beginnings of the universe must be transcended by ridding ourselves of our ignorance and insatiable desires that are at the root of the cycle, but the message of these teachings may be difficult to reconcile with our day-to-day lives in the modern world. The question that we must consider though is this: Where is the raging torrent that is modern civilization ultimately heading, as constant discoveries and innovations in science and technology swirl together with globalization and market principles to propel humanity ever forward without pause for breath or thought? Are we not heading, with ever-increasing speed, towards the end of the world? It may be to our benefit to contemplate the words of the poet Matsuo Basho, "The years that pass are also but travelers in time" or the last line of the song "Row, row, row your boat," that points out "Life is but a dream," which could reawaken in us an understanding of the value and fulfillment of a sense of being. Although constantly pressured by time on a daily basis, we should seek to value the passage of time from yesterday through to today and on into tomorrow with tenderness and love. In this way it is possible that the concepts of time cultivated in Indian philosophy and the traditions of Buddhism will blow a breath of fresh air that will bring about a paradigm shift in our own lives.