Title

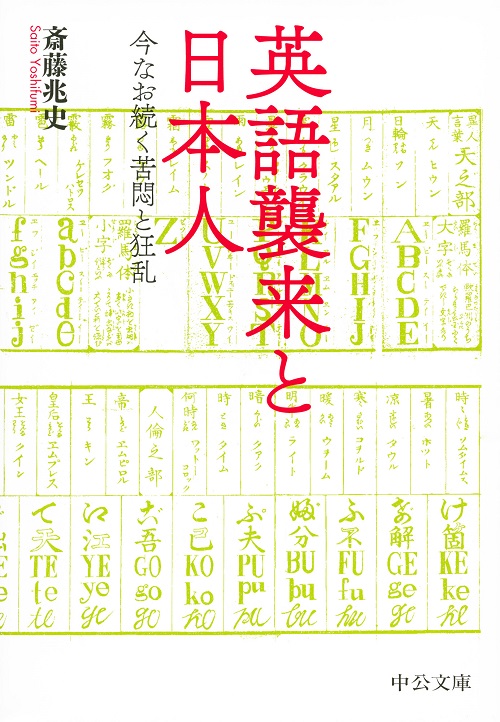

Eigo-shurai to nihonjin: imanao tsuduku kumon to kyouran (The English Language Invasion and the Japanese: their inveterate agony and craze over the language)

Size

224 pages, paperback

Language

Japanese

Released

January 19, 2017

ISBN

978-4-12-206355-6

Published by

Chuokoron-Shinsha, Inc.

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

This book undertakes a historical survey of how Japanese people tried to deal with English which first came to Japan more than 400 years ago.

In reviewing the history of English language teaching and learning in Japan, it is customary to refer to the ‘Phaeton Incident’ in 1808 as its starting point, for the Tokugawa shogunate, awakened for the first time to the military power of Britain, presently commanded Dutch-language interpreters in Nagasaki to start learning English. For the next forty years, Dutch-language interpreters made slow but steady progress in their study of English.

English studies in Japan made remarkable progress in the years following the opening of the ports at Shimoda, Hakodate, and Yokohama. The first decade of the Meiji Era witnessed the sudden emergence of English studies as a discipline primarily for obtaining Western knowledge and technology. The Meiji government employed many foreign teachers, mostly from Britain and the United States, as providers of higher education, and high proficiency in English consequently became a prerequisite for gaining access to advanced education. This government-driven Anglicization of education suddenly slowed down almost to a halt, however, when the Meiji government was confronted with serious financial difficulties caused by the Seinan War and had to drastically reduce the number of those high-salaried foreign teachers in its employ. Around the same time, the new domestic system of education had been well under way, and in 1885 the government at last put forth the policy for Japanizing the medium of instruction at all levels of education. Thus, English was ‘dethroned’ from its former dominant position in learning and education in Japan. In the latter half of the Meiji Era when Japan grew into a full-fledged modernized nation with due wealth and power, English studies, deprived of their practical functions, gradually shaped themselves into highly specialized disciplines of language and literary studies, and English was incorporated into school education as just one of the major subjects with its own routine functions of instruction and assessment.

The ELT reform that took place in the 1920s in the Taisho era against the backdrop of the popularization of education deserves special notice in relation to the history of English language education in the world. For the first time in its history, the teaching of English as a foreign language was highlighted in a state-driven educational reform.

After suffering great hardship during the period of militarism leading up to the Pacific War, in which English was designated as the language of the enemy and any pursuit even tangentially related to it was regarded as unpatriotic, English studies in Japan resumed their practices of research and education centred around universities, diversifying their respective disciplines and at the same time isolating themselves from as much proliferating ELT-related disciplines. The diversification and proliferation of English-related disciplines firstly brought about a structural division between the theory-based English-related academia and the practice-based ELT arena, and secondly, a dissociation of identity, especially among scholars of English literature and linguistics, most of whom were at the same time teachers of English and teacher-trainers by profession at universities but tended to prefer to define themselves in terms of specialization rather than profession.

Towards the end of the Showa era, as communicative foreign language ability drew more attention as one of the key abilities for surviving in the ‘globalized’ world and CLT as reportedly the most efficient methodology for teaching English, the tables were turned and ELT experts, many of whom in Japan were (and still are) SLA-based applied linguists, moulded their discipline in such a way that it might meet the social and educational demands for communication-oriented ELT and at the same time kept out old literature-oriented disciplines, thereby widening the professional gap between the camp of traditional English studies and themselves. Today, as a result of further diversification of English studies as well as of ELT-related studies, there are an enormous number of subdisciplines in either camp, which are pursued by individuals or small in-groups with little connection or overlap with each other.

At the beginning of the Heisei era the nationwide structural reform of higher education started, and faculties and departments of such ‘impractical’ disciplines as liberal arts and literary studies began to close down. The same utilitarianism and rationalism that characterized this reform has also found its way into ELT in the form of national language policies. Urged on by the social demand for practice- and communication-oriented language education, and based on the assumptions that ELT in Japan had focused ‘wrongly’ on grammar-based reading and writing and that the skill of ‘practical’ oral communication is a prerequisite for its people to survive in the 21st century and the age of ‘globalization’, the Ministry of Education launched a large-scale reform of English education policies. In 1998 and 1999 the Course Guidelines for junior high school and high school were revised so that greater emphasis should be placed on oral communication. The Course Guidelines for elementary school were also revised, and the subject of ‘Comprehensive Learning’ was introduced to enable ‘English conversation’ to be taught in the name of ‘foreign language education for cross-cultural understanding’. In 2009 the MEXT revised the Course Guidelines for high school (to be enforced in 2013), stipulating that English classes should be conducted primarily in English. In 2011 MEXT enforced the new Course Guidelines for elementary school, making compulsory the subject of ‘foreign language activities’ in which the ‘foreign language’ is virtually English.

(Written by SAITO Yoshifumi , Professor, Graduate School of Education / 2017)

Find a book

Find a book