Title

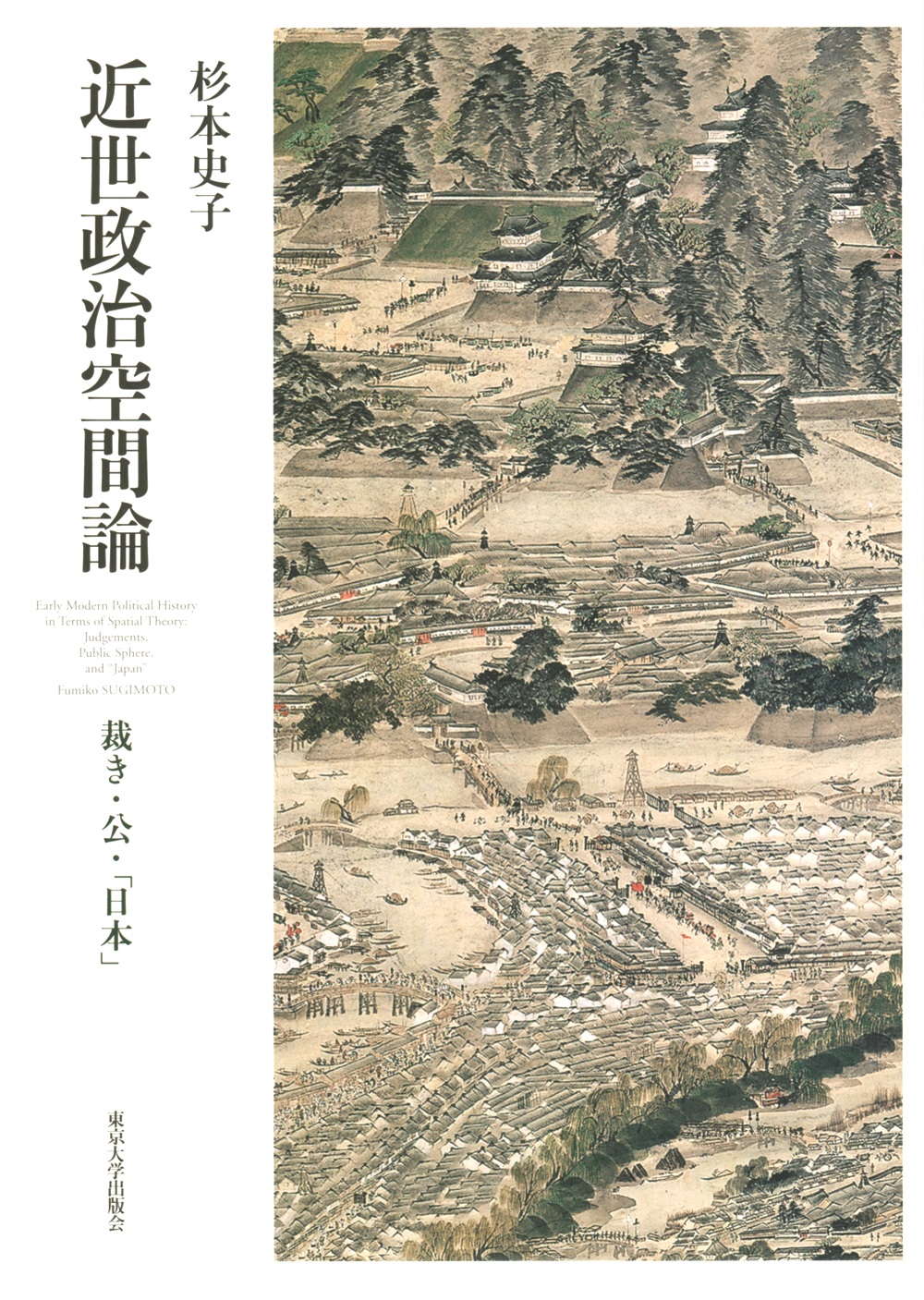

Kinsei-Seiji-Kukan-ron (Early Modern Political History in Terms of Spatial Theory: Judgements, Public Sphere, and “Japan”)

Size

394 pages, A5 format

Language

Japanese

Released

September 07, 2018

ISBN

978-4-13-020155-1

Published by

University of Tokyo Press

Book Info

Japanese Page

History is usually discussed in terms of a temporal axis. But this book discusses history by taking into account not only the temporal axis but also specific spaces and the relationships among people as subjective agents living and acting in these spaces. The title of the introductory chapter—“Space and Subjective Agency in the History of Early Modern Politics”—reflects this position.

In addition, the subtitle is “Judgements, Public Sphere, and ‘Japan’.” The topics this book sets out to reconsider are the quality of power reconsidered from the perspective of judicial “judgements,” the nature of society as revealed by the nature of the “public sphere,” and the framework of the idea of “Japan (Nihon).” This book delineates from these perspectives the transformation of society in the second half of the early modern period and the yearnings for a new world that were born of this transformation. The political history to which this book aspires is not limited to theories about political structures or the organization of power in a narrow sense. The aim is to analyze the above topics from a cross-sectional perspective transcending the framework of judicial history, information theory, publishing history, the history of the performing arts, and the history of Western studies.

As will be clear from the above, this books aims at a dynamic grasp of history, and it differs in its standpoint from the presentation of fixed geographical factors or a nationalist viewpoint into which geopolitics is liable to lapse (see Yamazaki Takashi, “Notes on Some Features of Geopolitics,” Gendai Shisō 9 [2017], pp. 56–58). By investigating distinctive features of historical spaces in each period, I have endeavoured rather to bring to light a concrete picture of changes in these spaces, and by this means I have aimed to throw into relief the meaning of the actions of historical agents that unfolded in these historical spaces.

In Part I (Edo Castle as a Political Space and Trials: Rethinking “Public Authority”), the object of analysis is Edo Castle, the centre of government at the time. Here, Edo Castle is taken to cover a large area that extended as far as the outer moat, and I divide it into the “core space” and “boundary space.” “Boundary space” is the area that lay inside the moat but where people of different social status could come and go when the gates were open and where distinctive features of the castle and the city overlapped. The existence of this space and its distinctive features had until now fallen into the gap between the study of political history and the study of urban history, and there had been little awareness of them.

The shogunate possessed preeminent powers among the daimyō, presenting, for example, norms to the emperor and imperial court, and it controlled vast landholdings and also cities and mines under its direct jurisdiction. But it ultimately did not build a truly centralized political system that might overcome the “shogunate-domain (bakuhan) system.” Within the shogunate, the Judicial Council fulfilled an important function as the shogunate’s centralized public authority, being responsible for passing judgement on disputes involving several spheres of control rather than a single sphere of control.

In this book, I focus on the fact that the Judicial Council was located in the “boundary space” of Edo Castle and elucidate some distinctive features of its judgements. Lying within the “boundary space,” the Judicial Council conducted trials while liaising on the one hand with central government offices in the “core space” and relying on functions of the city on the other. In circumstances characterized by a composite and complex organization of power among the shogunate and daimyō and the coexistence of several jurisdictions, the Judicial Council endeavoured to construct detailed judicial procedures that dealt not only with the contents of its judgements but also the way in which the results of its decisions were presented. But in the late eighteenth century this system of judicial procedures collapsed.

In Part II (The Transformation of the Pacific Ocean into a Political Space and “Nihon”: Expression and Publication of Information in a Global World), I focus on the emergence of maritime spaces as a stage for the international sharing of information and international competition in the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries. First, the measurement of longitude at sea became practically possible, and it thus became possible to gain a grasp of maritime regions, too, through grids showing longitude and latitude. Secondly, as a result of ocean voyages by steamships having become a reality, voyages that were markedly faster than before and the routes of which could be predicted became possible. Thirdly, in conjunction with these developments, ways of internationally sharing modern nautical charts containing this data began to be investigated, with Great Britain taking the lead. A state of affairs that might be described as an international system for sharing information about the sea began to encircle “Japan.” The formation of a modern territorial entity based on a single sovereignty in “Japan” began to be explored in the context of oceans that had taken on this new meaning. In Part II, the emergence of new oceans and the nature of a land-based society and state are understood as a continuum.

Within the Japanese archipelago, commercial publishing spread through society in the early modern period. Physical performing arts such as Kabuki linked up with this commercial publishing and developed into powerful forms of popular information media for giving expression to an ever-moving world. Simple publications describing novel events or future events were sold and read out aloud in shops, at temples and shrines, at festivals, and on the streets. In early modern society, which had lacked any notion of “freedom (or disclosure) of information” except at the very end of the Bakumatsu period, these information media began to create an invisible but large conduit that channelled the world outside “Japan” into the everyday world of its people. In this book, these media are collectively referred to as “media possessing functions of disclosure in an early modern sense.”

In this sort of society, it was scholars of Dutch learning and Western learning who comprehended the meaning of the emergence of new ocean spaces before statesmen did so. For those in positions of power, these scholars were a double-edged sword. On the one hand, they were indispensable for engaging in diplomacy with Western nations, but at the same time they were dangerous figures possessing a perspective that relativized the existing order centred on the shogun. They posed to the shogunate questions about how far to go in asserting the territorial extent of “Japan” and how to visually represent “Japan” when dealing with Western nations sharing information about oceans that was filled with data about longitude and latitude.

The map of “Japan” that they produced with a view to showing it to the nations of Europe and America looks at first sight like a modern map and does not seem at all strange to us today. But when we examine it in detail, taking into account the process whereby it was produced, a territorial map based on astonishing ideas quite different from those of today reveals itself. The external shape of “Japan” is rendered in a broken line. It is stated in the map’s legend that this broken line represents the line linking survey points, and it is thus shown to be a map grounded in purely scientific procedures. It adopts the stance of not including any ulterior political aims. At the same time, this map of “Japan” also included careful devices for visually representing as “Japan” even areas that were not internationally recognized as such.

Part III (Longing for a New Political Space and Ideas about the System of Government) sheds light on moves reflecting a longing for a new world that emerged in the midst of this social transformation in the latter part of the early modern period. I take up Watanabe Kazan, a scholar of Western learning who was also a professional painter who made a living by selling his paintings, as well as being a high-ranking retainer who supported his domanial lord. Conflicted by multiple identities, he was on the verge of grasping a new notion of “public” that was not dependent on one’s lord. This was a notion of “public” that was based on pride in his own abilities as an individual painter. Unable to bring his ideas to fruition in the form of a body of thought and still full of contradictions, he committed suicide. His final act of writing his name “Watanabe Noboru” in large characters on a piece of silk that he used for painting and describing himself as a “disloyal” retainer and “unfilial” son gave eloquent expression to his inner conflict.

But the idea of “public debate” (kōgi), which placed value on discussion among multiple agents rather than on the orders of superiors, turned into a torrent that swept through society. In the upheavals of the mid-nineteenth century, scholars of Western learning at the Institute for Western Studies (Kaiseisho) began to engage in independent activities that went beyond the original aims of the establishment of the shogunate’s institute for studying and teaching Western studies. And indeed in early 1868 there was established under their leadership in Edo, which was embroiled in civil strife, a new political space, namely, a bicameral assembly, a fact that had hitherto remained unknown. The lower chamber of this assembly was called “Place for Public Debate” (kōgisho).

(Written by SUGIMOTO Fumiko, Professor, Historiographical Institute / 2020)

Find a book

Find a book

eBook

eBook