Title

Returns (Returns - Becoming Indigenous in the Twenty-First Century)

Size

408 pages, A5 format

Language

Japanese

Released

December 16, 2020

ISBN

978-4-622-08962-9

Published by

Misuzu Shobo

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

This book is a Japanese translation of James Clifford’s Returns: Becoming Indigenous in the Twenty-First Century, Harvard University Press, 2013. The author, James Clifford, specializes in cultural research, focusing on the critical history of anthropology, and four of his books have already been translated into Japanese, including his edited book, Writing Culture.

Incidentally, the word “Indigenous” appears in the subtitle of this book. What is the image that this conjures in your mind? Speaking of the Japanese archipelago, for example, the Ainu people may come to mind. Or perhaps the “Indians” of the North American continent. Very roughly speaking, it might refer to the people who were colonized or deprived of their land and culture during the formation of the modern “nation-state.” In the past, these people were often discussed from the perspectives of “disappearing cultures and languages” and “cultures that should be saved from disappearance,” and from the dichotomies of modernity/tradition, and civilization/barbarism. However, what this book seeks to depict is a realistic modern history of the “Indigenous” people that cannot be understood by such a framework, as well as a portrait of the Indigenous people who are recovering or newly weaving together their own culture and lifestyle while cleverly negotiating with the neo-capitalist world.

An example is “Ishi’s Story,” which is featured in Part II of this book. Ishi is the name given to a man who was “discovered” in 1911 in California in the early 20th century and described as the “last wild Indian.” Ishi later worked as an anthropologist’s informant at the University of California Museum of Anthropology before dying of tuberculosis in 1916. Starting with Ishi in Two Worlds, which was written as a biography of Ishi by the anthropologist’s wife after his death and became a bestseller in the United States in the 1960s, the author explores the various consequences of this “story,” from the relationship between the anthropologist and Ishi and the post-war transformation of the representation of the “indigenous,” to the return of Ishi’s brain, which was originally sent to the Smithsonian Institution as a specimen, to the indigenous community.

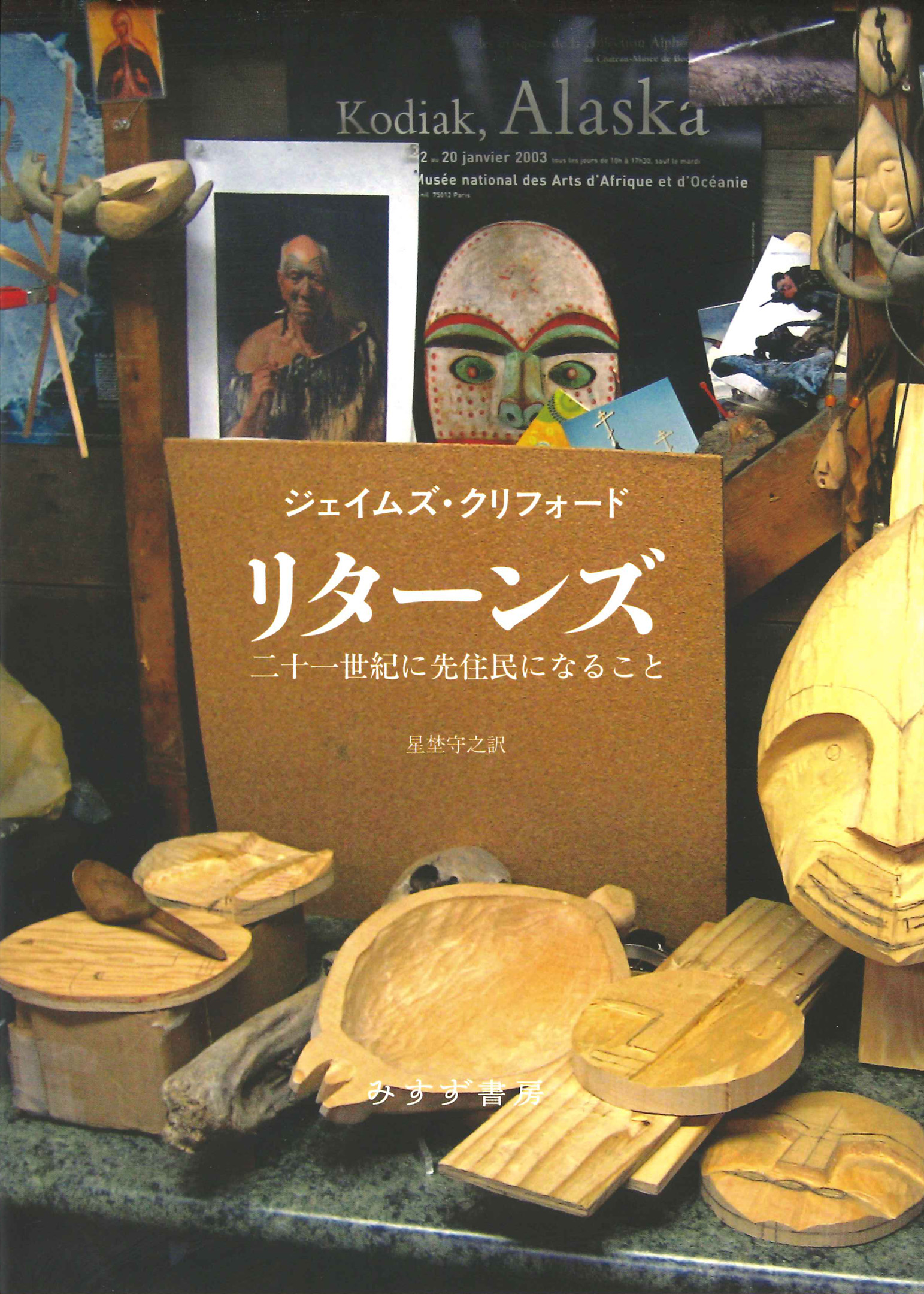

The chapter, “Second Life: The Return of the Masks,” in Part III is also very impressive. The setting is Kodiak Island in Alaska. The outline of the story is how an Indigenous community in this region, which was once part of Russia and later became part of the United States, coincidentally rediscovered in a local museum in France several masks, which were old cultural objects of their community and thought to have been lost. In this chapter, a discussion is provided on the complicated sense of identity of the local people, the relationship between the performance that is the exhibition and cultural revival, while focusing on how these masks returned to Kodiak Island as an exhibition.

The Indigenous culture is not timeless but contains a “present-becoming-future” in its own form––the subtitle of this book, “Becoming Indigenous in the Twenty-First Century,” may contain such an implication.

(Written by HOSHINO Moriyuki, Professor, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences / 2022)

Find a book

Find a book

eBook

eBook