Giant underwater waves keep corals cool Massive, long-term monitoring project shows why some reefs are protected from bleaching events

Researchers maintain a reef flat temperature logger in Iriomote, Japan. Photo by Alex S.J. Wyatt.

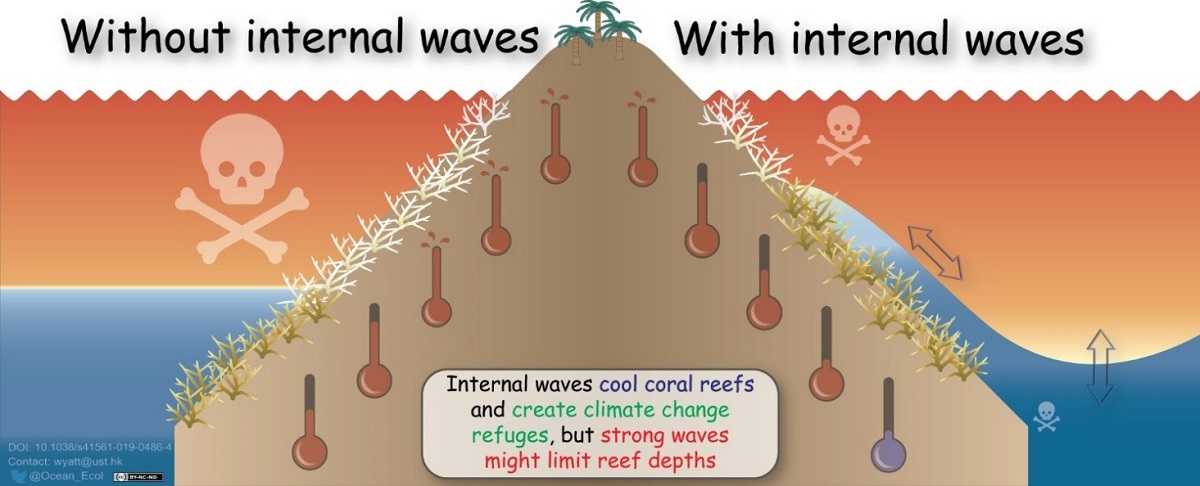

Surfers aren't the only ones living for good waves. Coral reefs throughout the Pacific Ocean may be staying alive in refuges created by waves of cooler water which protect them – at least for now – from the heat of climate change, according to ocean researchers in Japan, Hong Kong and the United States.

"Reducing heating events on coral reefs is important because coral reefs are gravely threatened by recent ocean warming. High water temperatures can cause serious coral bleaching, especially during El Niño heat waves," said Alex Wyatt, who began this study while working as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Tokyo and is currently an assistant professor at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

When water temperatures become too hot, the colorful microorganisms that live inside the corals are expelled, leaving the corals a ghostly white. Corals can sometimes survive a temporary bleaching event, but if the microorganisms stay away for too long, entire corals and large areas of reefs can die.

To identify conditions that might explain the unpredictability of which reefs die due to bleaching, researchers needed long-term, detailed temperature information for reefs from around the world.

Scientific diver entering the water for temperature logger maintenance in Funauki Bay, Iriomote, Japan. Image by Toshi Nagata.

Typically, researchers rely on ocean surface temperatures measured weekly from space by satellites. Satellites are important tools because they can easily monitor large, remote areas of the ocean surface, but they cannot measure temperatures in deeper waters surrounding individual reefs.

Temperature recorders placed in deeper water by scuba divers need to be maintained every six to 12 months when recording at short sampling intervals, for example every two minutes in this study. The expense and the risk of equipment being damaged or lost in a storm makes it difficult to maintain long-term ecological research projects like this one.

Overcoming all of those challenges, researchers obtained long-term water temperature measurements from 8 meters down to 30- or 50-meter depths recorded every two minutes that they could analyze from three coral reefs across the Pacific Ocean and also compare with satellite sea-surface temperature records.

The reef at Haapiti off the coast of Moorea, an island in French Polynesia in the remote South Pacific, has been monitored since May 2006. Iglesias Reef in the Gulf of Chiriquí, Panama, has been monitored since March 2012. The reef at Sabasaki in Funauki Bay, Iriomote Island, in far southwestern Japan, has been monitored since December 2014.

Within the data, researchers noticed fluctuations in temperature that lined up with the coming and going of large underwater waves.

The waves lapping beach shores are surface waves, a mere few meters tall and cresting every 5-15 seconds. Deeper beneath the surface, from 20-50 meters down, another type called internal waves travels slowly along the interface between the ocean's surface and deeper heavier water. Individual internal waves can be tens to hundreds of meters tall and the time between wave crests can be tens of minutes to hours long.

The waves bring cold water onto the corals, especially, but not only, in deeper parts of the reef, keeping the waters surrounding corals as much as 10 degrees Celsius (20 degrees Fahrenheit) cooler than the ocean surface temperature.

“The scale of the interaction is truly fascinating. An individual coral is experiencing temperatures linked to internal waves traveling hundreds to thousands of kilometers across the oceans,” said Wyatt.

Researchers maintain a reef slope temperature logger in Iriomote, Japan. Image by Alex S.J. Wyatt.

Providing even more benefit, internal waves are naturally most active during the summer months, when corals most need a chance to cool off. The detailed temperature data revealed that the underwater temperatures where corals grow become more similar to surface water temperatures when the effects of internal waves are removed in computer-simulated models. Those models are further supported by temperature data collected when waves are naturally absent, such as after large storms or during the winter months.

“Theoretically, it might be possible to create artificial, localized upwelling to temporarily manage ocean temperatures around coral reefs. Any such management would be extremely costly and no substitute for sustained and immediate global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and ocean heating,” said Wyatt.

This research was the product of a long-term collaboration between researchers at the University of Tokyo, the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, the United States Geological Survey and Florida Institute of Technology.

Infographic summarizing the role of internal waves in cooling reef habitats, as well as potentially limiting reef depths under strong wave forcing. Image by Alex S.J. Wyatt, CC BY-NC-ND

Papers

Wyatt, A.S.J., Leichter, J.J., Toth, L.T., Miyajima, T., Aronson, R.B. and Nagata, T, "Heat accumulation on coral reefs mitigated by internal waves. ," Nature Geoscience: November 18, 2019, doi:10.1038/s41561-019-0486-4.

Link (Publication )

)

Related links

- Summary of the academic article, written by the researchers

- Professor Toshi Nagata lab

- Professional website of Alex Wyatt

- Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute