Recorded history, unwritten future 125 years of the Historical Society of Japan

The Historical Society of Japan is the oldest academic historical association in Japan, and in November 2014, the Society’s 2,500 members nationwide celebrate its 125th anniversary. Born within the University of Tokyo, the development of the Society mirrors that of history as an academic discipline in Japan. Long after its birth within the Imperial University, in April 2012, a change in the Society’s legal form was the trigger that enabled it to spread its wings and became a truly national institution.

Ludwig Riess, o-yatoi gaikokujin

Figure 1: Ludwig Riess (1861-1928) studied under Hans Delbrück at Frederick William University (currently Humboldt University of Berlin) and mastered the study of modern history established by Leopold von Ranke. Riess came to Japan in 1887, lecturing on world history and the methodology of historical research until 1902.

The University of Tokyo Archives.

There is one person whose contributions to the foundation of the Historical Society of Japan cannot be ignored: the German historian Ludwig Riess, who came to Japan at the invitation of the Imperial University. Riess (figure 1) was one of many foreign advisors (o-yatoi gaikokujin) who came to Japan from Europe and North America after the Meiji Restoration. With backgrounds in fields including political science, law, military affairs and economics, these individuals were to aid Japan with incorporating advanced Western knowledge and technology. Riess introduced to Japan Leopold von Ranke’s modern source-based history, an empirical method of historical research that attempts to reconstruct facts through the collection and critical analysis of historical documents.

Professor Yoichi Nishikawa, Dean of the University of Tokyo Graduate Schools for Law and Politics, has researched Riess’ correspondence held at the Berlin State Library and transcripts of Riess’ lectures and his works written while at the Imperial University. He describes the atmosphere of Riess’ classroom.

“In Germany, universities emphasized the Übung (seminar) lesson style in order to have students learn historical research methods, and Riess utilized this teaching format in Japan as well. For example, in 1888 he covered the Shimabara Rebellion in his seminar. He and his students gathered Japanese historical materials and European documents including those from the Dutch Trading Post and from Christian churches. Comparing these documents, students were to reconstruct the course of the Rebellion from its initial rise through to its suppression. The results of this study were published as a research paper. Students did not simply listen to his lectures; rather, by actively involving themselves in historical analysis including through translating old Japanese documents into English, students became proficient at the modern methods used in historical studies” (figure 2).

Figure 2: Ryo Isoda, then a student of Riess, summarized and published the research findings gathered during Riess’ Übung (seminar) on the Shimabara Rebellion in Volume 1, Issue 13 of Shigaku Zasshi. Riess himself published a paper on the same theme in the East Asia Society of Germany Bulletin in 1890. Mr. Isoda became a lecturer at Imperial University and afterwards studied abroad in Germany and Austria. After returning to Japan, he worked as a professor at Tokyo Higher Normal School.

General Library, The University of Tokyo.

In his diary A Drop of Ink, Shiki Masaoka states that he failed out of the Imperial University because he failed Riess’ seminar. He goes on to admit that even afterwards, he would often have nightmares about examinations (entry from June 16). Masaoka was not the only student who experienced such tribulations.

“Reading over the lecture transcripts, one can see that Riess taught his seminar at the same high level that he taught in Germany. In letters written by another German who lived in Japan and knew Riess, one can find accounts describing Riess as being so strict towards students that he clashed with the University,” explains Professor Nishikawa.

The early introduction of modern history to Japan

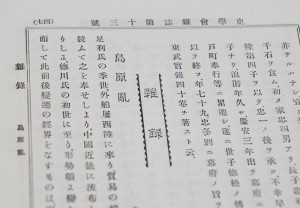

Once the Department of Japanese History was created at the Imperial University, Riess took the opportunity to press Professor Yasutsugu Shigeno and his other colleagues for the establishment of an academic society and the publication of a journal. These efforts resulted in the Historical Society of Japan’s first meeting, which doubled as a presentation session for the Society, being held on November 1, 1889 in the No. 10 classroom of the Faculty of Letters. On December 15 of the same year, the first issue of Shigakukai Zasshi (Journal of the Historical Society of Japan; later known as Shigaku Zasshi, or the Journal of Historical Studies) was published (figure 3). With the establishment of a network of researchers in the Historical Society of Japan, and a forum for publicly presenting research findings in Shigaku Zasshi, the study of modern history in Japan was born at the University of Tokyo 125 years ago.

Figure 3: Published for the first time in 1889, Shigakukai Zasshi (later known as Shigaku Zasshi) is Japan’s oldest academic history journal. As all papers are thoroughly examined via a strict review process before they are published, the journal offers very high-quality articles. The journal covers all historical topics in a comprehensive manner without being limited strictly to Japanese history, Eastern history, or Western history.

General Library, The University of Tokyo.

The oldest important historical journal still published today, the Historische Zeitschrift, was first issued in Germany in 1859, while the initial publication of the English Historical Review in the United Kingdom was in 1886 and the American Historical Review of the American Historical Association first appeared in 1895. Despite its origin in Europe, the foundations of modern history were established in Japan remarkably quickly. As of 2014, 123 volumes of Shigaku Zasshi have been published and, with the exception of the Great Kanto Earthquake, the Second World War and the University of Tokyo student protests, the Society’s Annual Meeting of Japan has continued to be held every year since its establishment in 1899.

An organizational transformation

Since its founding, the Historical Society of Japan has functioned with the purpose of being a ”society open to historians and to all people who harbor an interest in the study of any field of history, whether it be Japanese, Eastern or Western.”

After certification as an incorporated foundation in 1929, the Society operated under the regulation of the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture (currently the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology). With the revision of the public interest corporation system, however, from April 2012 the Society was removed from the Ministry’s oversight and reborn as a public interest incorporated foundation pursuant to the unified legal regulations of the Cabinet Office.

What do these changes mean for the Historical Society of Japan?

“To put it simply, considering that academic research is in itself an activity in the public interest, the Society decided to become an organization that works even harder to share the fruits of specialist historical research for the common good,” explains Professor Katsumi Fukasawa of the Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology, who served as the chairman of the Society at the time of its transformation into a public interest incorporated foundation.

Professor Fukasawa notes that there were many obstacles to the transition. So many, in fact, that the prevailing opinion of the Board of Directors and Board of Trustees at the time was that it was probably impossible to make the change. The reason for this reaction lay in the strict conditions that had to be met in order to be certified as a new public interest incorporated foundation.

“The toughest hurdles we had to clear were the requirements that directors were now forbidden from concurrently serving as trustees, and that the number of members of one family or organization could not exceed one third of the Board of Directors or Board of Trustees. As an overwhelming majority of directors had been elected from among the faculty of the University of Tokyo, the Society’s organization would have to undergo dramatic changes.”

A society open to all: the Historical Society of Japan’s guiding principle

Figure 4: Genpachi Mitsukuri

Genpachi Mitsukuri (1862-1919) went to Germany in 1886, where he first studied zoology and then changed his specialty to history, returning to study this subject in Germany and France. After coming back to Japan, he succeeded Riess as professor of Western history at the Imperial University. His book History of the Great French Revolution (in two volumes) was praised as Japan’s first academic book addressing revolutionary history.

General Library, The University of Tokyo.

Another option on the table was abandoning the transition to a public interest incorporated foundation and instead applying to become a legally less restrictive ordinary incorporated foundation. However, this would be a passive or less constructive choice.

“Ultimately, the reason we were able to both greatly reduce the number of people on the Board of Trustees and adhere to the one-third rule applying to the Board of Directors was because we concluded that this reform would actually lead the Society towards new developments and greater progress. The Historical Society’s original purpose was not to be a closed academic group completely within the confines of one university. Rather, the Historical Society always intended to be a nationwide academic organization with its doors open to the outside world. This aim was clearly discussed as early as 1913, when Professor Genpachi Mitsukuri addressed the topic in his speech ‘The Past and Present of the Historical Society of Japan’ during the 15th Society Annual Meeting. Moreover, the Society was certified as an incorporated foundation during the first year of the Great Depression (1929) so that it could widely disseminate the outcomes of academic research based upon the Society’s awareness of its role as a nationwide scholarly organization. By reaffirming this guiding principle of our Society, we were able to arrive at the decision to engage in organizational reform.” (Figure 4).

Lessons from 125 years of history

Newly reorganized, the Historical Society of Japan will host four public symposiums from September through December 2014 to commemorate its 125th anniversary (figure 5).

Professor Toshiko Himeoka of the University of Tokyo Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology, as one of the newly-appointed directors of the Society, is deeply involved in preparing for the symposiums. “These four symposiums are the fruits of our collaboration with the Osaka University History-Education Seminar, the Tohoku Historical Society, the Fukushima University Historical Society, and the Historical Society of Kyushu. They are also a new endeavor for the Society. The Historical Society of Japan counts not only University of Tokyo alumni among its members, but also many graduates of history departments in other universities. One could say that it is precisely because of our nationwide network that we have been able to organize these large-scale events. Each of the four venues features a unique theme and these symposiums will not act as places to merely present one’s research but will provide opportunities for dialogue and lively discussion.”

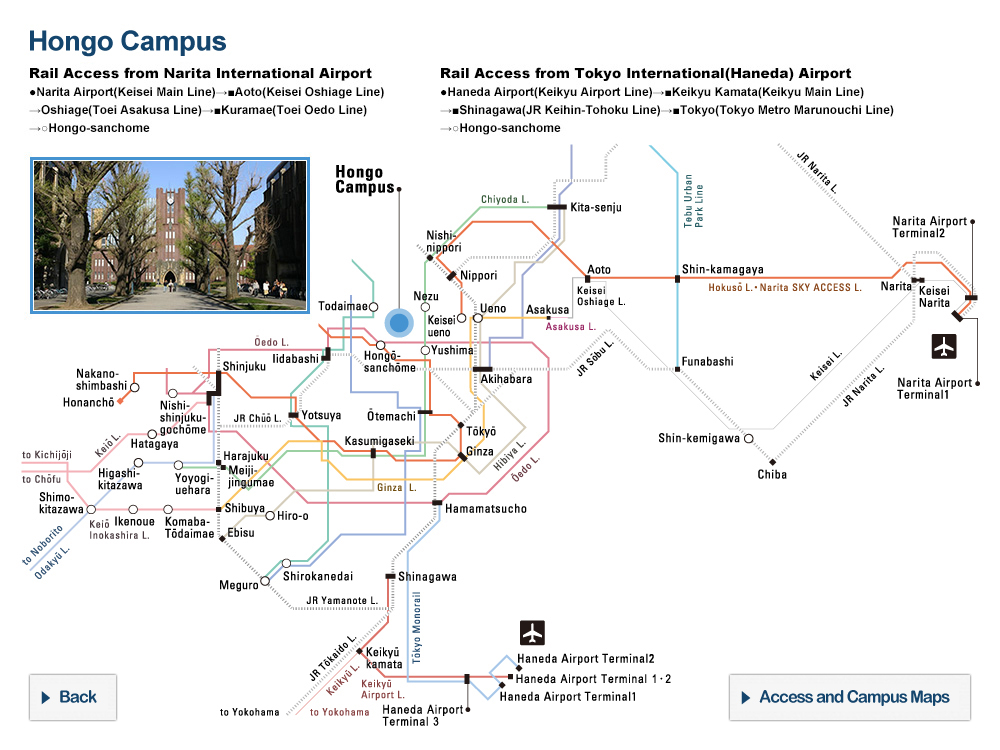

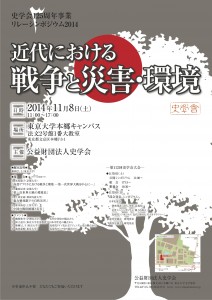

The theme of the third symposium, which will take place at University of Tokyo’s Hongo Campus on November 8th, is “War, Disaster and the Environment in Modern History.” Exactly 100 years after the outbreak of hostilities, this is a novel attempt that reconsiders the First World War as a disaster, analyzing its environmental impact from a modern viewpoint. Professor Himeoka concludes, “This 125th anniversary is an opportunity for the Society to reflect on its past and consider its future, but the Society’s core principle of utilizing empirical methods in the academic study of history continues unchanged. E. H. Carr said that history is ‘an unending dialogue between the past and present.’ The Society’s 125 years of experience and academic achievement will continue to be the guiding principle by which we live.”

Public symposium at the meeting of the Historical Society of Japan

War, disaster and the environment in modern history

The University of Tokyo Hongo Campus, from 11:00 to 17:00 on Saturday, November 8, 2014

Interview/text: Takahiro Naito (writer). Translation: Whitney Matthews, Raita Taguchi.

Researchers (alphabetical order)

Professor Katsumi Fukasawa

Professor Toshiko Himeoka

Professor Yoichi Nishikawa