Overcoming assumptions about Islamic Art The advantages of an East Asian perspective

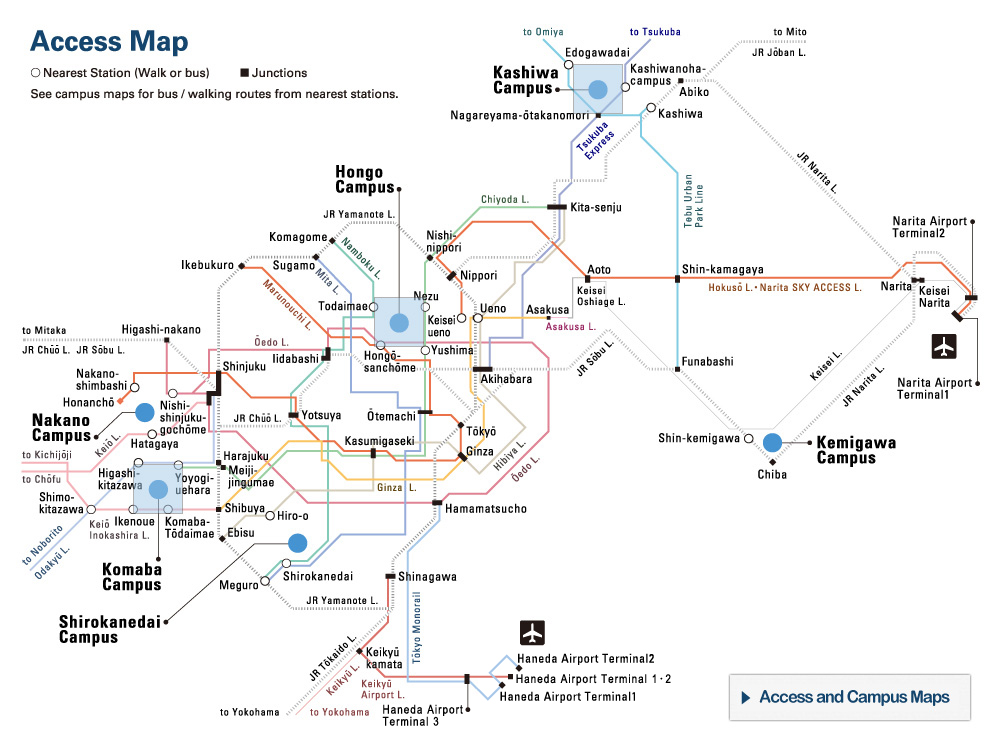

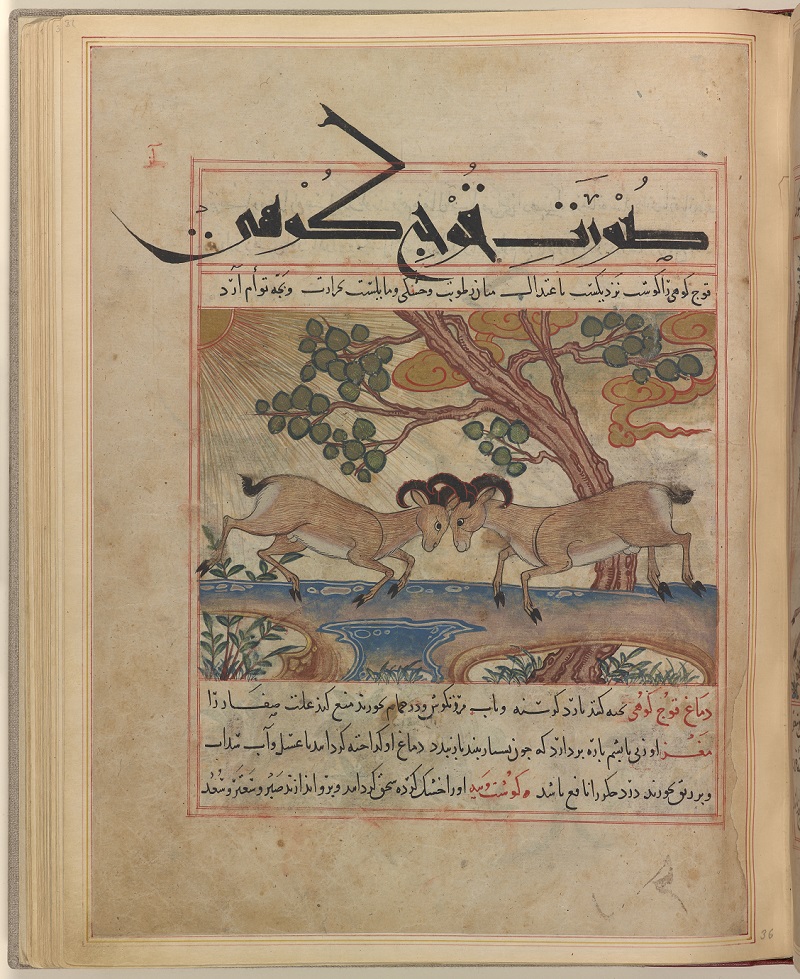

Figure 1: Manāfiʻ-i ḥayavān., (Uses of Animals)

Manāfiʻ-i ḥayavān., (Uses of Animals) is a scientific text that discusses the medicinal uses of many different animals. It is the oldest extant example of manuscript painting from the Ilkhanid period. A notable characteristic is the intermixing of a sectional view, used traditionally by the artists of western Asia, and a bird’s-eye view, which was an imported technique. (In this painting, the tree and body of the rock are examples of the former, while the upper surface of the rock and the mountain rams standing on it are examples of the latter.) Through careful analysis, Masuya confirms that three artists worked on this manuscript, one painting in the traditional style, the other two in the imported style.

Ibn Bakhtīshūʻ, ʻUbayd Allāh ibn Jibrāʼīl. Manāfiʻ-i ḥayavān., fol. 37r, Mountain Rams. Maragheh, Iran, 1297-1298 or 1299-1300, and 19th cent. Credit: The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. MS M.500, fol. 37r. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913), 1912.

Whether they understand the language or not, the traveler to a foreign country is likely to find their interest in the local culture pushed to new heights by everything their eyes see—from the faces of the people and how they dress, to the look of the buildings and neighborhoods, to the unfamiliar foods that appear in markets and restaurants. So too with objects of art that have deep roots in the culture, often going back many centuries.

Professor Tomoko Masuya of the University of Tokyo’s Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia is an Islamic art specialist. In the broadest sense, this means she studies the history of art in any region of the world where Islam is or was the primary religion—which makes it a field of tremendous reach both geographically and historically. But within that vast expanse, one of Masuya’s principal focuses has been manuscript paintings.

In this context, a manuscript refers to a book copied by hand. Such books were decorated with illuminations, illustrations, or both; the former first appeared in copies of the Quran, the most important of all texts in the Islamic world, and the latter accompanied works of science, literature, history and other writings. Manuscript paintings of this kind saw two separate strains of development, one in the Arabic-speaking regions that stretched westward from the Arabian Peninsula along the Mediterranean coast, the other in the Persian-speaking world centering on Iran.

Verifying what you see

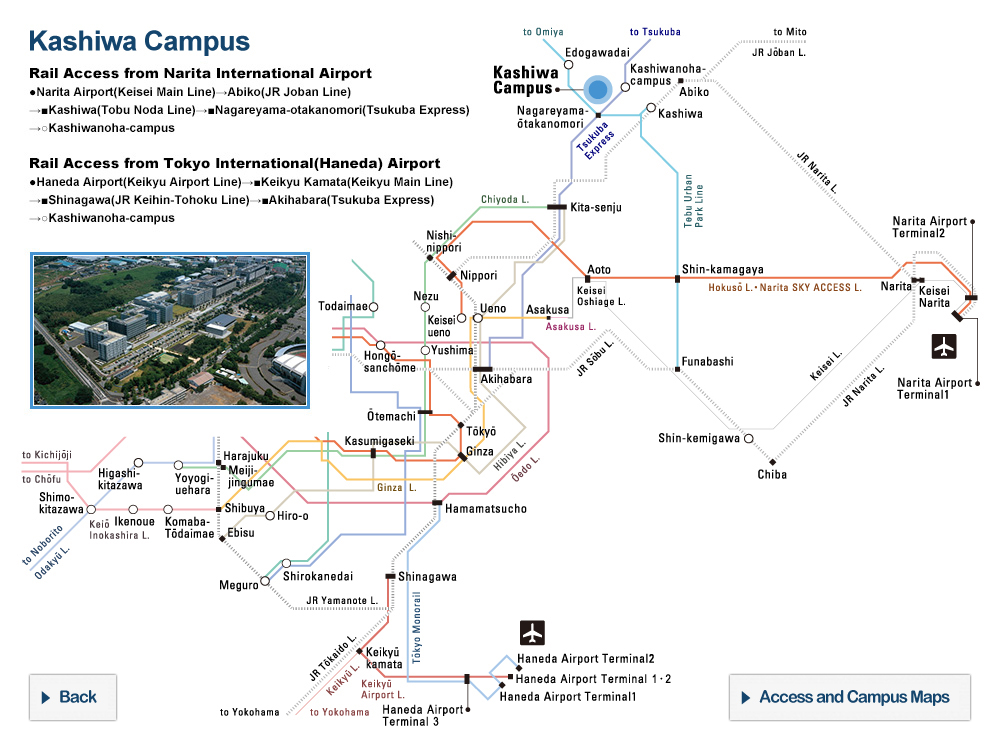

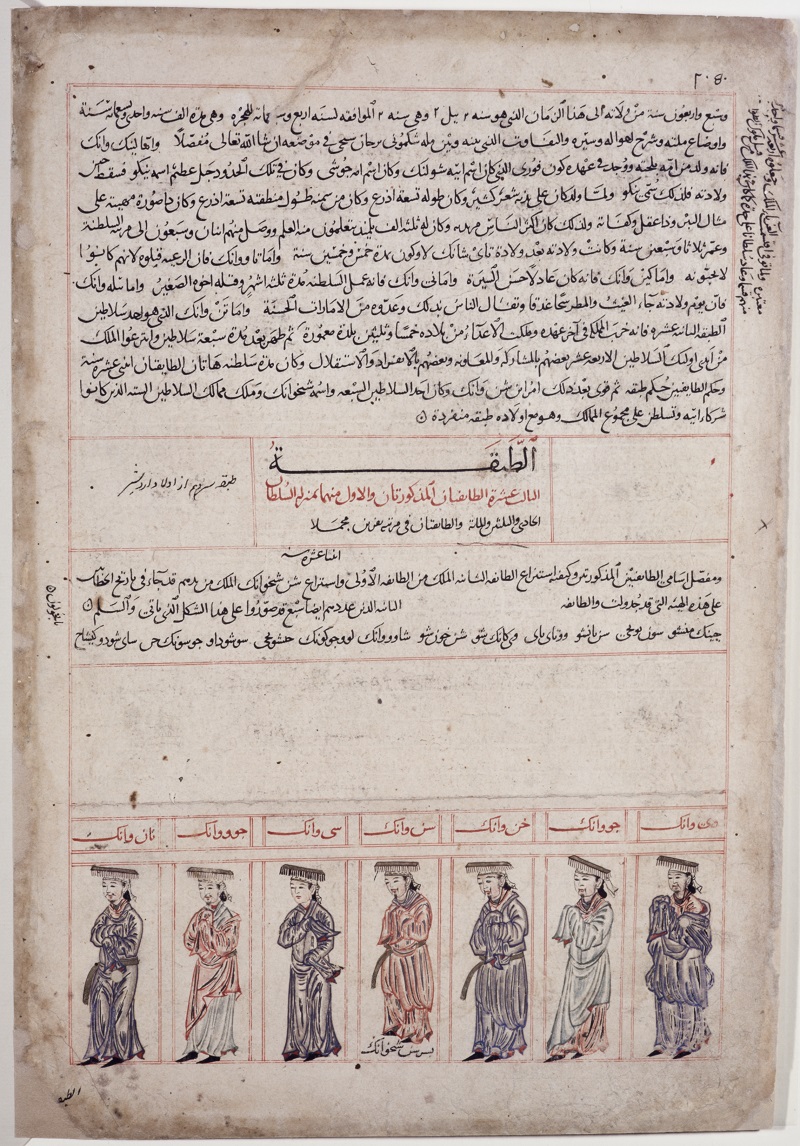

Figure 2: “Seven Emperors of the Warring States,” in Jāmi‘ al-Tawārīkh (Compendium of Chronicles)

The large blank space below the middle was left there by the copyist for the illustrator to fill with portraits of the thirteen princes from the Spring and Autumn Period (ca. 771–476 B.C.), whose names are listed on the line directly above, but the artist has not understood this and left it open. If the artist had been able to read Arabic, they would have recognized the names even though they are not written in red and filled the space with thirteen portraits, just as they did for the seven princes of the Warring States period (ca. 475–221 B.C.) at the bottom, whose names are indeed written in red.

“Seven Emperors of the Warring States,” in Jāmi‘ al-Tawārīkh (Compendium of Chronicles), by Rashīd al-Dīn, Arabic language manuscript, Tabriz (Iran), 714 A.H./1314-15 A.D., The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art (London), MSS727, folio 10b.

European specialists on Islamic art have long asserted that the Ilkhanids (1258–1353), who ruled the west region of the Mongol Empire in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, represent a significant turning point in the history of manuscript painting. Noting that images associated with Chinese art began appearing in the paintings—especially in the Persian-speaking areas where the Ilkhanid territory was located—scholars identified direct Chinese influences in the manuscript artwork.

Since clouds with curls and spirals, dragons, and other motifs identified with Chinese origin are indeed found in manuscript paintings from that period onward, the assertion might seem quite natural (figure 1). But one art historian from East Asia could not imagine that it was a direct influence.

“From the first time I saw them, these elements just didn’t seem very Chinese to me,” says Masuya. “If you look at Chinese landscapes, you can see how generations of Chinese artists refined the tradition to a very high level of sophistication. But these images were obviously on a completely different level.”

This was only an impression, as an East Asian art historian, but it prompted her to see if she could verify it. She began by examining the paintings in Jāmi‘ al-Tawārīkh (Compendium of Chronicles), a history compiled by an early-14th century minister of the Ilkhanid dynasty named Rashīd al-Dīn. In a close study of the section on early Chinese history, she made one new discovery after another (figure 2).

A portrait of a bearded Empress

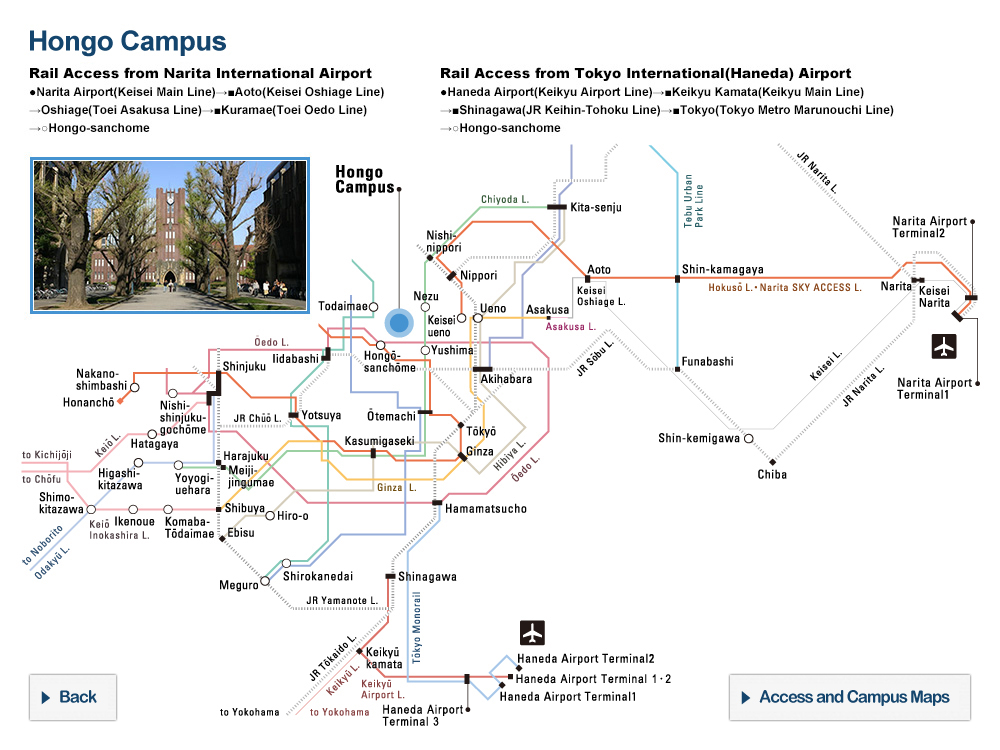

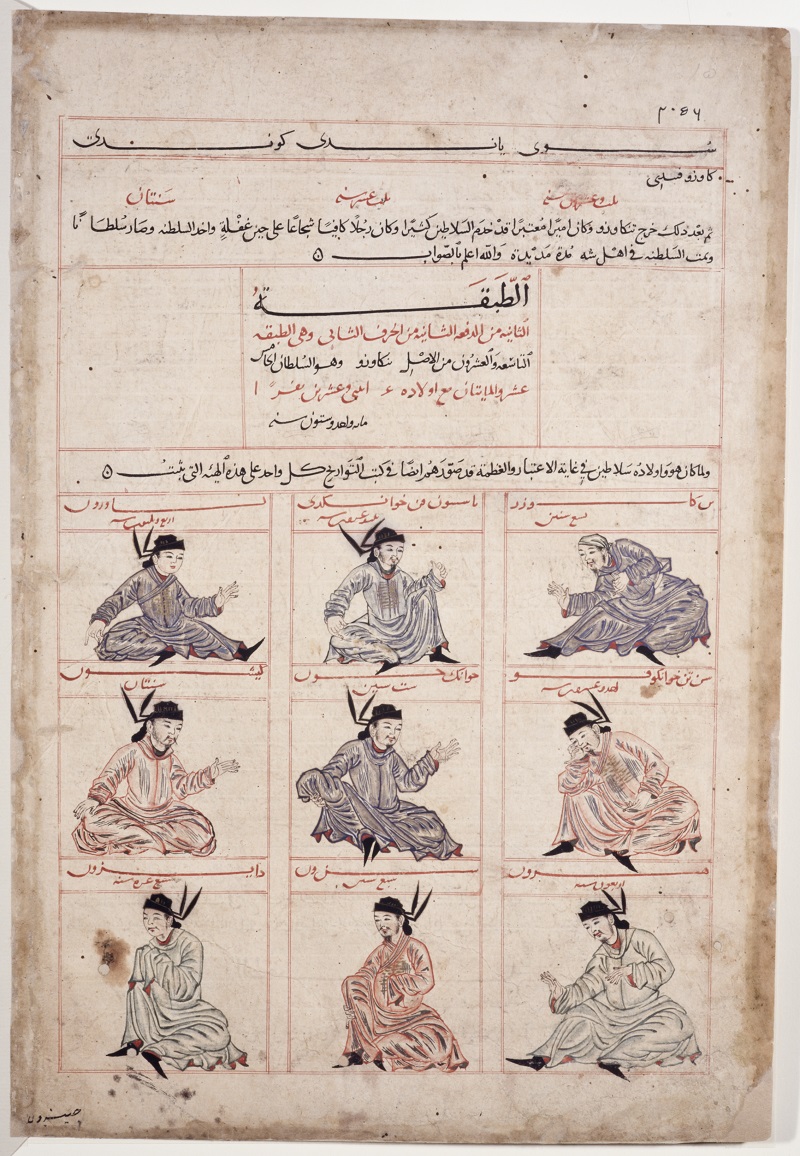

Figure 3: “Nine Emperors of the Tang Dynasty,” in Jāmi‘ al-Tawārīkh (Compendium of Chronicles)

This folio pictures nine Chinese rulers from the Tang dynasty. The rightmost figure in the second row is labeled “Empress Wu Zetian,” indicating it is intended to be a portrait of the only empress in Chinese history to exercise power in her own name. But the face sports a beard!

“Nine Emperors of the Tang Dynasty,” in Jāmi‘ al-Tawārīkh (Compendium of Chronicles), by Rashīd al-Dīn, Arabic language manuscript, Tabriz (Iran), 714 A.H./1314-15 A.D., The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art (London), MSS727, folio 16b.

“For example, facial features and costumes showed distinct differences from Chinese paintings of the period. Silver is used for the whites of the eyes—something not done in China. Emperors are shown with headwear that only a person of lower rank would wear, and a king known to have died at an early age is shown as an adult. . . . My biggest surprise was a portrait of Empress Wu Zetian that shows her with a beard," (figure 3).

Based on her analysis of these and other observations, Masuya concluded that the illustrations were in fact drawn by non-Chinese artists who knew little about China, and who also could not read Arabic. She published her findings in the book Isurāmu no Shahon Kaiga (Islamic Manuscript Paintings), which appeared from Nagoya University Press in February 2014. Her breakthrough came from being able to recognize elements that anyone not from an East Asian background would be likely to overlook. Being Japanese and familiar with Chinese history and art played a crucial role in leading her to the new perspective.

Onward into untrodden territory

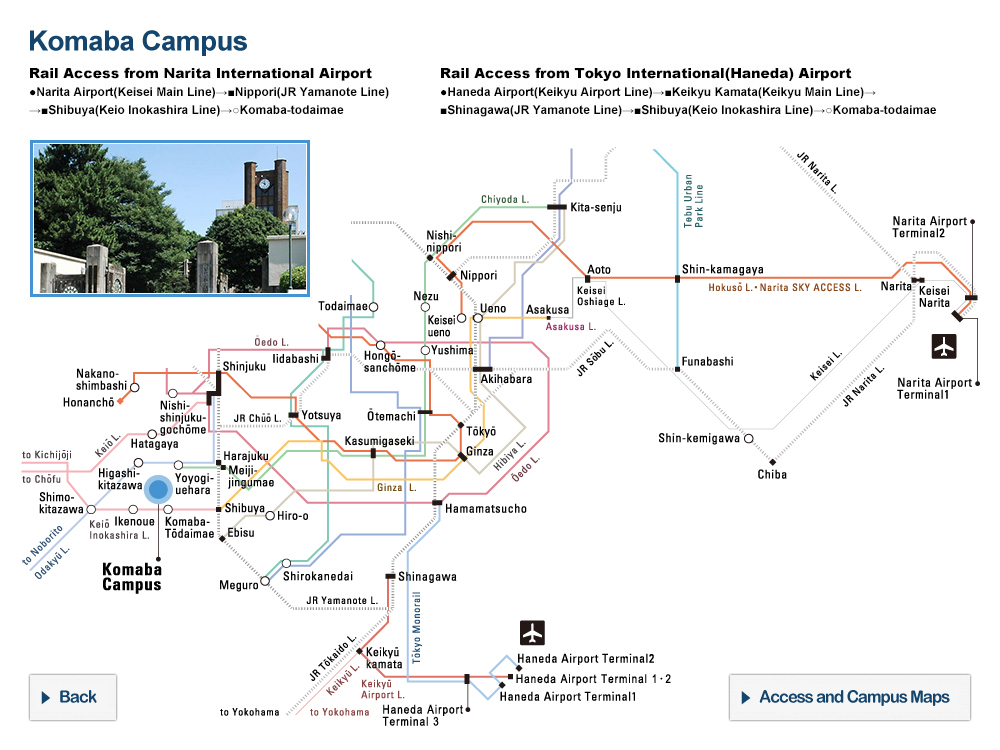

Figure 4: Potttery sherd

A specimen from among the collection of some 390 Islamic pottery sherds belonging to the Ohara Museum of Art in Kurashiki. Masuya discovered a potter’s signature identical to one on a pot in the collection of the British Museum.

Ohara Museum of Art.

Masuya notes that her new theory has yet to generate much of a response from the field. “It’s different from usual because at this point I’ve only published these findings in Japanese. I haven’t had a chance to get them out there in English yet. There aren’t all that many people working in this field anywhere in the world, and when you limit it just to Japan, there’s really only a very small handful of specialists. . . .”

A field with few specialists means a field with much untrodden territory. Since so much about Islamic art is still poorly understood, a great deal remains to be discovered. This makes the field all the more rewarding to work in.

Masuya’s expression softens as she speaks of a student who is about to complete her advanced graduate study—only the second such student she has had in ten years. She is working with her to classify a trove of some 390 Islamic pottery sherds unearthed at Fusṭāṭ, a former capital of Egypt (figure 4). This “miraculous collection,” as it is sometimes called, was gathered by the early-20th century Western-style painter Torajirō Kojima, and now belongs to the Ohara Museum of Art in Kurashiki, Okayama Prefecture. “Art has the power to transmit culture directly, in a single glance, without having to rely on language,” says Masuya. It seems we can look forward to a not-too-distant day when the professor and her students will promote the beauty of Islamic art to the world, bridging East and West.

Interview/text: Jiro Takai

Researchers

Professor Tomoko Masuya

The Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia

Links

The Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia

References

Tomoko Masuya. Isurāmu no shahon kaiga [Islamic Manuscript Paintings], Nagoya University Press, 2014.