Towards a feminist future Women in the media and online

March 8th marks International Women’s Day, a day on which we bring attention to ongoing issues involving gender equality, reproductive rights, and violence against women. This year, Professor Toko Tanaka of the University of Tokyo’s Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies provides insight on the current position of women in media, the history behind that position, and what to expect from communication media moving forward.

© Kyosuke YAMAMOTO (August 10th 2022. Los Angeles International Airport, United States)

Media, women, and representation

── What are some of the issues that you grapple with in your research on media?

People have started noticing in recent years that nearly all academic fields are lacking in perspectives from the position of gender, sexuality, and other minoritized viewpoints, and this is also true of media. Such perspectives have not been given much importance historically with regard to media, but recently I have been working on laying the groundwork for rethinking media from these perspectives.

To give an example from a project on which I served as an advisor at the NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute, the ages of the women and men that appear on television news are completely different. In the case of Japan, though I suspect this is also the case elsewhere, only women who are both of a certain age and conventionally attractive appear on television. Meanwhile, men with a variety of appearances may appear on TV, as they are selected based on their job title, intelligence, experience, occupation, and so forth. For women, their outward appearance is factored into that selection process.

── Why specifically do you examine media from the perspective of gender and sexuality?

After the late 1960s, second-wave feminism was incredibly active both in Japan and abroad, but after a time, it was met with backlash. Using the term “post-feminism,” people began saying that the “job” of feminism was complete and that women should do their best as individuals — this is an attitude that continued from the 1990s into the 2010s. Even conducting in research on feminism or sexuality came to be viewed as “old fashioned” and unnecessary.

However, disparities and inequalities that feminism had been trying to address never disappeared. Some think these disparities are the result of some innate difference in the abilities of women and men, but so much of it comes back to childhood. When we observe and analyze the differences between how girls and boys are raised and the expectations that are placed on them, we can see that there are many girls who are unable to develop their abilities, or who want to develop their abilities but do not receive adequate support from those around them. Both the home and the media are overflowing with messages that tell us that women should be one way and men should be another way, and these do not go unnoticed by children.

Feminism, popular media, and rethinking the “consumer”

── When is it that the public backlash against feminism began to change?

It was not until 2017 that we really began to see a shift in broader public opinion, but we see shifts in other areas before that. Feminism and women’s self-expression have long made advances in relation to whatever media has been available at a given time. For example, during second-wave feminism, women used paper media such as galley prints and pamphlets to write about the discrimination they were facing, and they would mail these pamphlets all over the country so that people could read them and connect with one another.

During the backlash in the 1990s, third-wave feminism quietly advanced, albeit not through the mainstream political and economic arenas, but rather, through popular culture. For example, in movies, TV dramas, and manga, there was a huge increase in works that subtly dealt with feminist themes, and these themes circulated among popular culture consumers into the 2000s.

Once social media emerged as a communication tool and the smartphone made its debut in 2012, feminism from popular culture began spreading via the internet. One of the major examples of this spread is the worldwide growth of hashtag movements. In order for an idea or new way of thinking to spread, I have found that the power of media is inevitably necessary, whether it be video, newspapers, television, or now, the internet.

── What is it about popular media that has allowed feminism to spread?

Typically, in so-called “traditional” media like television and newspapers, the relationship between producer and consumer is actually quite rigid, with those who produce media content on one side providing to those who consume it on the other side. The problem, however, is that the media industry has long been an elite field; what this means in Japan is that the people who produce traditional media content are predominantly men with elite backgrounds. As a result, traditional media is filled with male-centered content, making it difficult for women and girls to find content that reflects their needs.

That being said, among traditional media, publishing media is quite different. Magazines, for example, have a great deal of segmentation by not only gender, but also by age. There are also many magazines in general aimed at women, so there is a surprisingly high proportion of female magazine and book editors. Additionally, this is why there is a relatively high amount of content produced for women in the form of manga, novels, and so forth.

── How has the internet affected the relationship between producer and consumer?

First of all, the internet changed that relationship from a unidirectional one to a bidirectional one, allowing producers and consumers to come together into a kind of “prosumer” — and anyone can be a “prosumer.” What this means for women and girls who have less social power is that they are able to transmit information on their own and express themselves, their perspectives, and their desires en masse. Moreover, through the use of hashtags, for example, not only are they able to connect with one another, but their thoughts and opinions become visible all at once as a large idea to be shared.

The internet has also become a place where young women are empowered to discover abilities that would have been previously overlooked. For example, Japanese magazines that focus on criticism or contemporary philosophy have long had male writers, and this was also true of pop culture criticism. Nowadays, however, it is possible for editors to find young female critics on social media, which means they are able to discover new writers in new networks that are not based on, for example, who-knows-who from a particular university. This has led to more and more young women writing articles for well-known magazines as critics or reviewers.

The future of life on the internet

── What are some of the other difficulties with internet communication nowadays?

The style of interaction on the internet makes it difficult to judge which opinions are sound and justified, as opinions that may be fundamentally flawed in terms of morality, human rights, or social justice can receive an enormous amount of support through likes and retweets. Though some support for these opinions could well come from bot accounts designed to do exactly that, at the same time, the very validity of humanity’s values that we have developed over the course of modernity and which are necessary for advancing social justice and equality, are being decided by the power of numbers.

Another difficulty is that the internet is a place where the private and the public are seamlessly connected, but we still have not agreed on how to behave in such a space, making even having a dialogue difficult. People from a variety of different backgrounds and cultures who may not have normally met one another are all together in the same space. In a decontextualized, open setting, it can be difficult to know where another person stands, or even how to understand the words they are using, making it easy for people to be incredibly irresponsible with their remarks. This is something that has changed drastically since social media in the 2000s. Before, people would be connected only with those who have something in common such as the same school, the same interests, and so forth, and this is still the case on Facebook. On Twitter, however, someone may think they are simply sharing their opinion, but they are actually putting it on display in an incredibly public space. Moreover, you can strike up a conversation with anyone, which is how celebrities and university researchers, especially women, end up targeted for arguments by complete strangers.

── How do you see social interaction on the internet developing from here?

At this point, social media is already over a decade old, and though it is continuing to develop in different ways, one thing I am especially apprehensive about is the Metaverse. Though VTubers and other livestreamers already use avatars to some extent, I am concerned about what happens when online communication spaces become more three-dimensional and how avatars can perpetuate dominant beauty standards. For example, people who have issues with their appearance may create an avatar that reflects how they want to be seen, but those choices may also reflect dominant hierarchies of beauty and race that privilege, for example, Western-styles of beauty, especially Anglo-Saxon. Additionally, though there is the benefit of people with disabilities being able to utilize able-bodied avatars if they would like, at the same time, the virtual space in which people see themselves could become even more skewed towards able-bodied individuals.

Furthermore, I worry that when the interactional space itself becomes more three-dimensional that we will see an increase in sexual harassment, and surveys have found that there is indeed a great deal of harassment within the Metaverse. The developers behind the Metaverse are primarily men, and people have noted that the design of Metaverse spaces hardly seem like somewhere that women can enjoy themselves in peace. There’s a subfield of geography called feminist geography, which deals with how women and other minoritized people have been left out of the conversation on urban design. While this field usually deals with physical spaces, I think it will be incredibly important or even necessary when considering the new virtual spaces like the Metaverse created by media in the future.

I think there is still a lot of research to be done on internet platforms, especially as online communication spaces take on more physicality, and that analysis needs to be informed by gender, sexuality, human rights, and minoritized perspectives. It is not as though the internet itself is somehow corrupting people’s minds, but rather, pre-existing social prejudices and discriminatory attitudes end up flowing onto the internet, and we do not know yet how to deal with that. In order to create media and communication spaces that serve the needs of everyone, more diverse voices need to be involved from the beginning, both academically and demographically.

Toko Tanaka

Professor, Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies

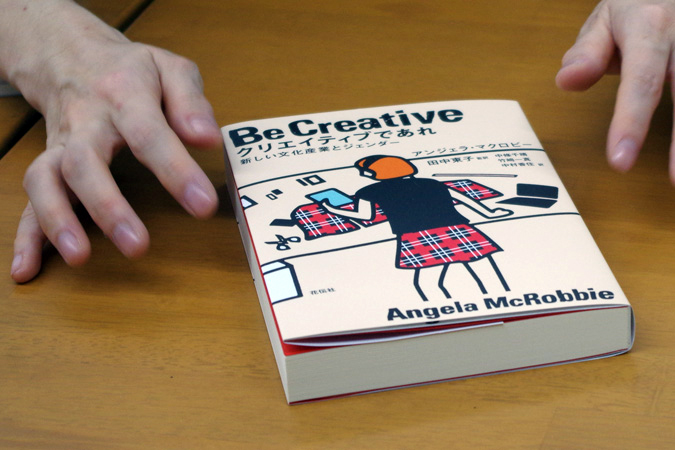

Ph.D. (Political Science) from the Graduate School of Political Science, Waseda University. Author and collaborator on numerous publications, including Media bunka to jendā no seijigaku: Dai san pa feminizumu no shiten kara (The Politics of Gender and Media Culture: Perspectives from Third-Wave Feminism) (Sekai shisōsha, 2012); co-author of Watashitachi no “tatakauhime/hataraku shōjo” (“Our ‘Fighting Princesses and Working Girls’”) (Horinouchi Shuppan, 2019); editor of Girl’s Media Studies (Hokuju Shuppan, 2021); supervising translator of Be Creative: Making a Living in the New Culture Industries by Angela McRobbie (Polity, 2016) (JP: Kuriatibu de are: Atarashii bunka sangyō to jendā, Kadensha, 2023); and co-translator of Feminism and the Politics of Resilience by Angela McRobbie (Polity, 2020) (JP: Feminizumu to rejiriensu no seiji: Jendā, media, soshite fukushi no shūen, Seidosha, 2022) and There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack by Paul Gilroy (University of Chicago Press, 1991) (JP: Yunion jakku ni kuro wa nai: Jinshu to kokumin o meguru bunka seiji, Getsuyosha, 2017).

Interview date: February 24th, 2023

Interview: Hannah Dahlberg-Dodd, Yuki Terada