Buddhist scriptures enter new age Digital humanities project evolves with technology

Some of the volumes of the Taisho Shinshu Daizokyo, containing scriptures from India, China and Japan, are shown. © 2018 The University of Tokyo.

In 2008, after 14 years of painstaking work, a group of researchers led by University of Tokyo humanities professor Masahiro Shimoda rolled out a massive digital collection of Buddhist scriptures that people around the world could access through the internet.

But the group’s work was far from done.

The digital project archived the Taisho Shinshu Daizokyo, containing scriptures and their interpretations from India, China and Japan. The 100-volume collection, based on Buddhist texts whose origin dates back 2,500 years and comprising more than 100 million Chinese characters, was originally published by researchers including Junjiro Takakusu, a Buddhism scholar at Tokyo Imperial University (the predecessor of UTokyo), over a 10-year span beginning in 1924.

What was missing from the first digital-text version, though, was more than 6,000 kanji (Chinese logograms, some of which have been incorporated into the Japanese writing system) contained in the printed version; the characters could not be displayed digitally, as they had not been encoded for computers.

Last year, nearly a decade after that first digital release, the group managed to get 2,800 of these uncoded characters registered on Unicode, the encoding standard for handling text on computers. It means that these characters can at last be displayed on computers, thus being spared digital oblivion.

“Government bodies had not been particularly concerned about the possibility that certain kanji could go extinct, that they would not exist on computers,” said Shimoda, a professor of Indian philosophy at the Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology, in a recent interview. “A number of private-sector projects were set up over the past 20 years to create a new system for displaying unregistered kanji, but they proved unsustainable when their funding ran out.”

To have new characters listed on Unicode, the Geneva-based International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has to approve them first, and only then does Unicode register the characters.

The addition of the 2,800 letters by Unicode also marked the first time that the ISO adopted a proposal by academics. Until then, only government entities were allowed to suggest additions to the ISO.

Early struggles

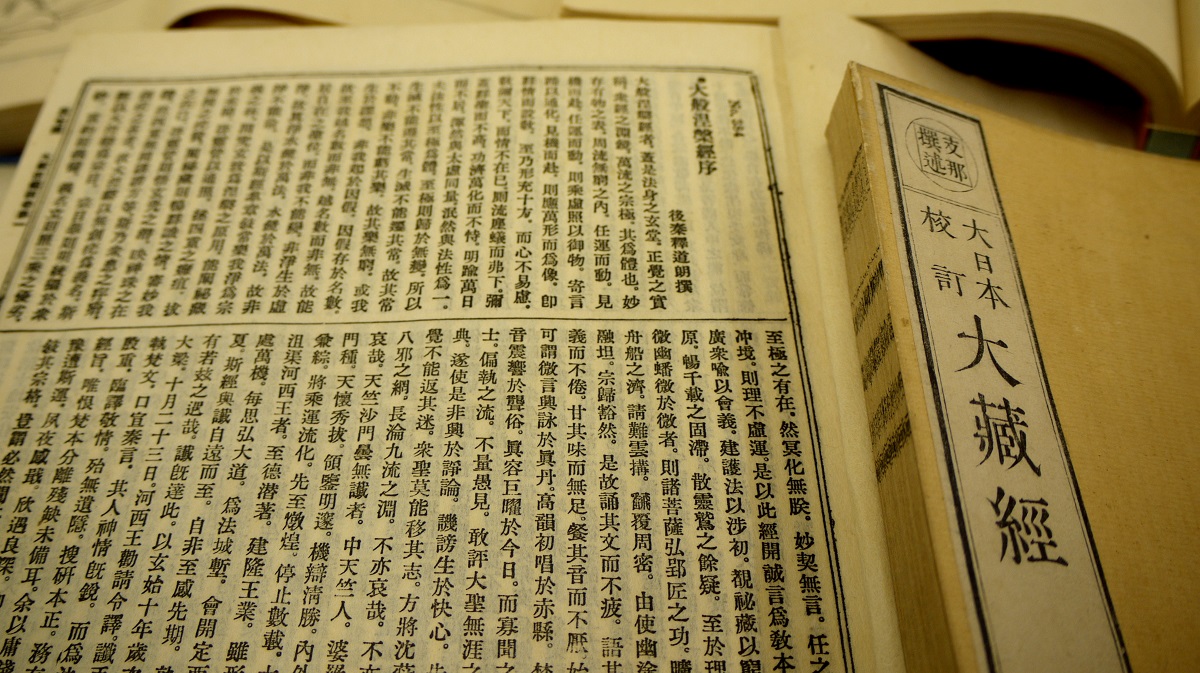

An image database of the Taisho Shinshu Daizokyo was unveiled in 2016. © 2018 The University of Tokyo.

The project, called SAT (short for Saṃgaṇikīkṛtaṃ Taiśotripiṭakaṃ, the Sanskrit phrase for the Taisho Shinshu Daizokyo), has come a long way. It was started in 1994 by Yasunori Ejima, a researcher of Indian philosophy at UTokyo, who had predicted that digital data would soon become a standard resource for researchers.

After Ejima’s death in 1999, Shimoda took over as project leader, mobilizing about 300 scholars and volunteers in total.

In the early days, project members manually typed all the kanji from the books into word processors and saved them on floppy disks, as personal computers and the internet were not yet available to most people, recalled Shimoda.

The researchers also processed characters that were not in the word processors’ dictionary by combining components of existing kanji or entering them as black boxes in the text with annotations. Later, the group introduced optical character recognition, converting scanned characters into digital format.

But early versions of the OCR software were so poor in recognizing characters that it took researchers an exhaustingly long time to correct the errors, Shimoda said.

Technological advances

UTokyo humanities professor Masashiro Shimoda (right), who has led the SAT digitalization project, poses for a photo with Kiyonori Nagasaki, a researcher from the International Institute for Digital Humanities. © 2018 The University of Tokyo.

The project got a big boost in 2005 when researcher Kiyonori Nagasaki joined the team. That same year, the SAT team started preparing a petition to submit to the ISO, collecting evidence on how these thousands of unregistered kanji appear in the scriptures. In 2012, Shimoda called on top international Buddhism and humanities researchers, based mainly at universities in the United States, Britain, Canada and the Netherlands, to sign the group’s petition so it could propose character additions to the ISO.

That led to the 2017 listing of 2,800 kanji characters on Unicode 10.0, which, incidentally, also added dozens of new emoji, icons like smiley faces commonly used in electronic messages. In fact, over 2,000 emoji have been recognized by Unicode since 2009, demonstrating how written communication has diversified over time.

“We really don’t know how many kanji are out there in total,” Shimoda said. “There are so many yet to be discovered. It is SAT’s mission to lay out a road map for rediscovering these characters within the ISO framework.”

The SAT database has expanded its functions, such as dictionaries and links to other Buddhist canon databases, undergoing major updates in 2012 and 2015. In 2016, cooperating with Japanese art and Buddhist art experts, the group released the 12 remaining volumes of the collection that cover illustrations, such as those of Buddha and bodhisattvas who spread his teachings.

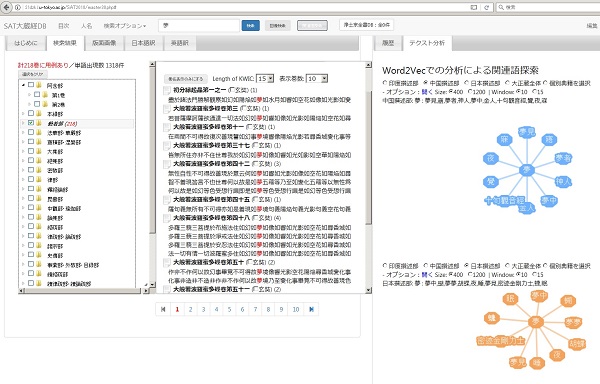

The latest SAT database has incorporated artificial intelligence technologies to make searches of related words from the entire database possible. © 2018 The University of Tokyo.

In the latest version, made public in April, some portions of the scriptures were translated into contemporary, plain Japanese. SAT was also linked to a database in Japan — as well as a catalog compiled by the Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg in Germany — of related academic papers.

In addition, search functions that incorporate Google’s artificial intelligence technology have been introduced on a trial basis. For example, when users look up the word bosatsu (bodhisattva) on the database, they can also get a mind map-like web of related words around it. This way, for instance, users can easily compare what’s written in the text compiled in Japan with that compiled in China.

“Daizokyo is divided into three parts — a part each for texts compiled in India, China and Japan,” Nagasaki, now a researcher at the Tokyo-based International Institute for Digital Humanities, said. “The searches can contrast the different contexts in which a word is used.

“I am often asked by Buddhist monks how AI would change the way Buddhist texts are read. They are all serious about understanding the scriptures, so I think a search function like this would be useful.”

Value of trial and error

Shimoda says he finds value in exploring new functions, adding that it offers researchers in Japan a foothold from which to engage in the international standard-making process, and perhaps more importantly, to create an academic infrastructure that better suits the needs of Asian studies than the one that exists now, which was created mostly by scholars in Western countries.

Each of the 100 volumes of the Taisho Shinshu Daizokyo is boxed and kept at the office of the International Institute for Digital Humanities, located right outside the university’s Hongo Campus. © 2018 The University of Tokyo.

“While changes are hard to predict, it’s important to collaborate with projects overseas so we can participate in the international standard-making process,” Shimoda said. “There’s value in sharing the ‘error’ part of trial and error.”

Thanks to the database, SAT members have received numerous offers from institutions interested in joint research. According to Shimoda, more than 10 international research projects are currently underway at UTokyo, including those with Leiden University in the Netherlands, the University of British Columbia in Canada and the University of Munich in Germany.

“There are many research projects that cannot be carried out without SAT,” Nagasaki said. “For example, the Tokyo National Museum has numerous fragments of wood from medieval Japan with passages from Buddhist scriptures written on them. They are elaborately handwritten sutras, but I understand that researchers for long were unable to pinpoint which parts of the scriptures they were from. I’ve heard that SAT managed to identify the sections of the scriptures that match the writings on these wood fragments.”

Shimoda says he wants to apply the know-how gained from the SAT project to other fields and nurture a new generation of digital humanities researchers.

“We consider SAT to be just one model for building a knowledge base in the digital age,” he said. “We want to take it as far as we can, and understand and share our findings.”

Interview/Text: Tomoko Otake