Science for all UTokyo experts discuss ways to make science inclusive for students with disability

Guide blocks are installed from the Akamon Gate of UTokyo’s Hongo Campus to the Faculty of Education building.

All students should be given an opportunity to study in university if they wish to, in the academic field of their choice. But in reality, many students with disability often give up going to college due to a variety of barriers they encounter during their primary and secondary education. The barriers can be especially daunting for students pursuing the so-called STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) areas, resulting in numerous cases of students ending up in other fields.

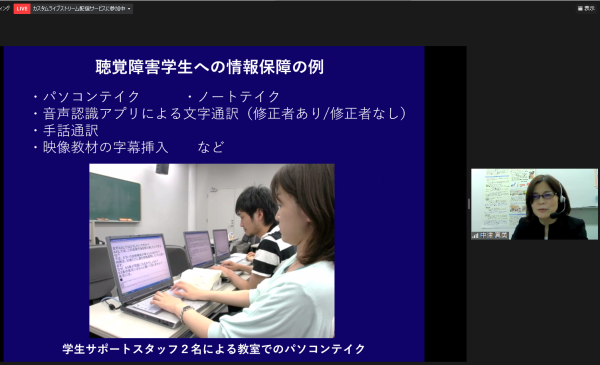

Disability and accessibility experts at the University of Tokyo discussed how to make higher education, particularly in the sciences, more inclusive at a webinar held Nov. 21, as part of the science communication event Science Agora 2020. The 90-minute session, titled “Inclusive Science for Students With Disabilities,” drew nearly 30 participants. For the session, closed captions were provided, using speech recognition software.

The webinar was planned and moderated by Shinichiro Kumagaya, associate professor at the Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology (RCAST). Kumagaya, who was born with cerebral palsy, completed his undergraduate and graduate studies at UTokyo. He now leads a unique research area called “user-led research,” where people, including those with disabilities, study their own difficulties or disorders. Kumagaya is also director of UTokyo’s Disability Services Office (DSO), launched in 2004.

Associate Professor Yuji Matsuda from the Department of Architecture at the Graduate School of Engineering is an expert on universal design. As a DSO member, he has been involved in the university’s efforts to improve the physical accessibility of its campuses.

Matsuda said that universities are different from other educational institutions in their scale, roads and buildings. Compared to elementary schools or high schools, universities are characterized by their large number of buildings on spacious grounds. On campus, there is no separation of pedestrians and cars, and buildings are connected by a wide path, which is used by pedestrians, bicycles and cars.

The front entrance of Faculty of Engineering Building 2 on UTokyo’s Hongo Campus.

UTokyo made the Faculty of Engineering Building 2 wheelchair-accessible by installing a slope to a side entrance.

Many buildings at UTokyo are decades old and require walking up stairs at the entrance. Many classrooms have fixed chairs and desks, and most toilets are not accessible by wheelchairs.

The “barrier-free” laws require that buildings meeting certain conditions be wheelchair-accessible. Stringent standards apply to the entrances, hallways, elevators and toilets. However, unlike special needs schools, public health centers and nursing homes, universities are required to only “make efforts” to meet such standards.

UTokyo has dealt with the problem in many ways. For buildings where it is difficult to improve accessibility at the entrance, the university has installed a slope nearby. They have laid guide blocks for users with loss of sight, and have installed tables on which to place bags inside toilet booths, after consulting with the users on the most convenient position.

“I must admit that the university’s actions have been reactive,” Matsuda told the webinar. “With institutions like UTokyo, where many of its buildings are old, it is extremely difficult, both in terms of cost and time, to renovate to meet the needs of all users in advance. On the other hand, we have users with specific accessibility issues, so it is important to quickly and thoroughly hear them out and conduct repair work as needs arise.”

The university has done more than improving physical accessibility. Mami Nakatsu, project research associate at DSO, has coordinated support for students and faculty with disabilities for 15 years.

The office has nine staff members, including two full-time faculty, she said, noting that DSO is unique in that its staff includes people with disabilities.

A student with disability entering UTokyo applies to receive support, then meets with office staff for interviews and consultations to decide on the assistance to be offered. For disabled students to fully participate in class activities, the office offers a range of services to ensure they have access to the same level and quality of information as others. For example, at the request of students who are blind or with low vision, DSO magnifies texts in textbooks and other study materials, transcribes them into Braille, and digitizes texts so they can be read out by software. Graphs are also translated into text so students can understand their content.

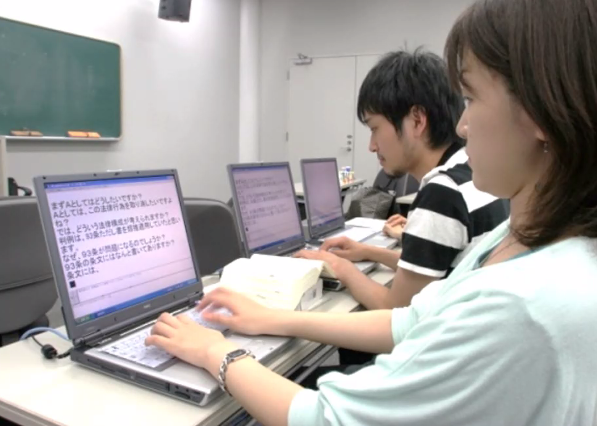

Student supporters take notes for a hard-of-hearing student.

The office has also provided information accessibility support by placing student support staff in classes. The support staff sit alongside the student, look at the instructor’s writing on the board and whisper the content to the student in a small voice. For students with total or partial hearing loss, student supporters enter the instructor’s words into a PC, or manually take notes for them.

This academic year (2020), UTokyo moved its classes online due to the coronavirus pandemic. It means that student support staff could not provide support in the classroom. For hard-of-hearing students taking online classes, student support staff have helped instead by listening to the lectures also remotely and correcting errors in captions provided by speech recognition software, Nakatsu said.

“When considering support, we value the process of coming to a consensus through dialogues between students with disabilities and the university,” Nakatsu said. “The university doesn’t unilaterally tell a student that, for example, `You have hearing issues, so you need a speech recognition app.’

“Instead, students and the university try to decide together on the type of support they receive. That’s the concept behind The Act on the Elimination of Discrimination against Persons with Disabilities. The support for person A and person B, who have the same disability, may be different, and even for the same student, the content of support may vary from scene to scene.”

Kumagaya commented that, with the outbreak of COVID-19 and the start of remote learning, DSO has had to drastically review its services. Along the way, he and his staff have realized that the true “bottleneck” for equal access to education is not the technology, but the faculty members, he said.

"When I was a student (at UTokyo), I experienced many inconveniences because we did not have DSO yet. But I remember fondly that my professors worked very hard to help me. Today, we have a support system in place, but I sometimes feel that there is a tendency for the university to leave everything up to DSO. I think everyone on campus needs to think about ensuring access to information for all.”

Associate Professor Shigehiro Namiki, a wheelchair user like Kumagaya and also at RCAST, introduced a list of researchers who, despite their disability, succeeded in STEM fields.

The French astronomer Pierre Janssen (1824-1907), who discovered helium, German physicist Gustav Kirchhoff (1824-1887), who discovered the Kirchhoff’s circuit laws, and the British physicist Stephen Hawking (1942-2018) all had difficulty walking. People with hearing loss, a missing arm, schizophrenia or dyslexia have won the Nobel Prize.

Physicist Stephen Hawking arrives at Kennedy Space Center in Houston, Texas, after enjoying a zero gravity flight in 2007. ©NASA

“Reasonable accommodation” is a key concept in barrier-free legislation that refers to a change or adjustment to a rule, policy or practice that may be necessary for a person with disability to not be discriminated against. The concept was in fact developed and refined through court cases involving admission into medical schools, Namiki said.

Many medical schools in the United States stipulate that applicants must have “observation,” “communication,” “motor,” “quantitative,” and “behavioral and social” skills and abilities. Students with sensory or motor disabilities were not allowed to enroll for a long time because they were judged incapable of performing such medical procedures as diagnostic touching or listening to bodily sounds, catheter insertion and cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Now, however, people with disability can perform these tasks by using technology and receiving the support of others through reasonable accommodation.

For example, by using an electronic stethoscope that visually displays the heartbeat as a waveform, you can examine a patient even if you are hard of hearing. Or if a cervical spinal cord injury impedes your ability to move your hands, you can examine a patient without problems if an assistant or nurse places a stethoscope on the patient’s chest for you.

The point is to identify what can and cannot be substituted by technology or helpers, Namiki explained.

What can be substituted can be covered by reasonable accommodation. In other words, that which can be covered by reasonable accommodation is not “essential” to the work. “Today, technology is expanding the scope of what can be covered by reasonable accommodation,” Namiki said.

For students who want to pursue a science career, RCAST researchers have recently launched the Inclusive Academia Project, putting together a list of active scientists with disability around the world. The researchers plan to make the list public soon so these “role models” can be shared, according to Namiki.

Questions from the audience included: “I have a speech impediment. Do you know any software that converts text to voice?” (Answer: There are screen readers. Some professors use such software for their classes because they have difficulty speaking, and their lectures are exceedingly popular); “How many student support staff does UTokyo have? Is their number enough to meet all the demand?” (Answer: Approximately 180 people; the office recruits staff as needs arise); “How can I support hard-of-hearing students in small-group discussions?” (Answer: Make sure to arrange seats so everyone’s face can be seen, then have everyone stick to rules, such as enunciating their names first, showing their lip movements to the hard-of-hearing student, and starting to speak after making eye contact.)

“Science, which is a human activity, should not be limited to certain people only,” Kumagaya said as he concluded the session. “I believe that, by having a diverse group of people participate, we can transform science so it can generate richer knowledge and technology. That way, the knowledge and technology produced by science would also become more useful for people with disability, who tend to be left behind by such advances.”

Text: Tomoko Otake