Japanese venomous snakes with characteristics that differ from island to island The evolution of habu sheds light on the development of the Nansei Islands

Habu Studies @ Kagoshima Prefecture

Shosaku Hattori / From Shimane

Project Researcher at the Amami Laboratory of Injurious Animals, the Institute of Medical Science

Co-author of Mongoose to Harujion (The Mongoose and the Philadelphia Fleabane) (Iwanami Shoten, 2000) (1,900 yen + tax)

Habu (Protobothrops flavoviridis) is a venomous snake endemic to Japan. Mr. Hattori, a researcher based in Amami Oshima, not only spends his days facing habu, but also examining the development of the Nansei Islands over time based on the evolution of this venomous snake, which differs by island. By using habu as a “hub,” he links the ecology of snakes with geographical changes occurring over the course of 5 million years. Come and experience the world of habu – it won’t bite!

Naka-ryukyu is believed to have detached from the main continent about 2 million years ago.

The Amami Laboratory of Injurious Animals, run by the Institute of Medical Science at the University of Tokyo, was initially established as the Oshima branch of the University’s Institute for Infectious Disease. Records show that Taichi Kitajima, the first researcher stationed at the branch, had it built as a facility to collect venom from habu snakes. The laboratory has thus been engaged in the study of habu for more than a century; the venomous snake is certainly fascinating enough to warrant such extended investigation.

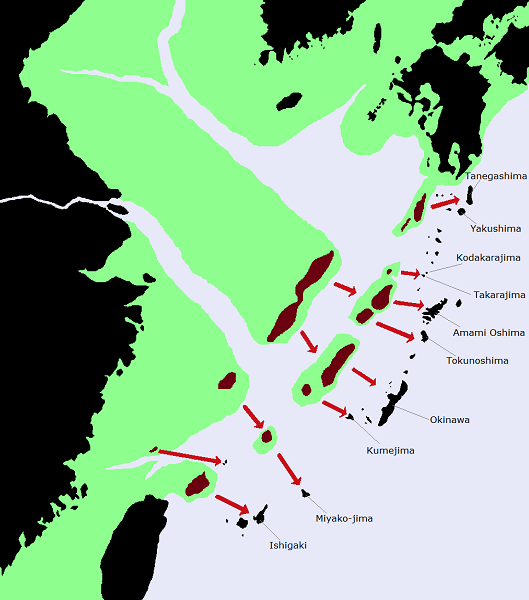

About a hundred years ago in Amami Oshima and Okinawa, biologists observed animals that did not exist in mainland Japan, including the habu snake, Okinawa tree lizard (Japalura polygonata) and Ishikawa’s frog (Odorrana ishikawae). They recognized that the islands were inhabited by the descendants of animals that survived emigration north from the southern region of Asia, and proposed a biogeographic boundary called Watase’s Line between Yakushima and Amami Oshima of the Nansei Islands. This proposal is based on the theory that the ancestors of these animals moved north during the period when the Nansei Islands formed a land bridge, from around 5 million to 2 million years ago.

The area surrounding the Amami Islands and Okinawa is called “Naka-ryukyu” (Central Ryukyu), and efforts are being made to have this area registered as a UNESCO World Natural Heritage site. The area's biggest attraction is its great number of endemic species. Close relatives to animals such as the Amami rabbit, Ryukyu spiny rat, Lidth’s jay, habu and Ishikawa’s frog cannot be found anywhere else in the world. There are species related to the habu found in the Yaeyama Islands, in Taiwan as well as the southern part of China, but evidence from genetic distance suggests that the habu diverged from these related species about 10 million years ago. This genetic distance cannot be explained by the hypothesis that habu reached the Naka-ryukyu area by island hopping, and strongly implies that most of the species that remained on the continent and did not make it to Naka-ryukyu became extinct.

Explaining the habu’s shedded skin to elementary school students.

In addition to Watase’s Line, there is a biological boundary called Hachisuka’s Line, which is drawn between Kume Island, where habu live, and the Miyako Islands. If the two boundaries had once extended to mainland China, it was most likely at the mouths of the old Yellow River and the old Yangtze River. This leads to another hypothesis: The ancestors of the endemic species of Naka-ryukyu were left behind in the area of the current continental shelf between the two rivers, and became extinct during the subsequent ice age. This is the simplest explanation as to why the species are endemic to Naka-ryukyu. The Earth’s temperature was declining gradually in the period when the Nansei Islands were formed; thus, animals at the time must have moved south instead of north. In the meantime, the landmass on the edge of the continent became detached due to the expansion of the East China Sea, turning into islands floating in the southern part of the Kuroshio Current. The living organisms that had moved to these islands managed to survive the cooling of the Earth. This hypothesis is called “Noah’s Ark in the Miocene.”

Habu living in Naka-ryukyu continued to evolve, developing stark differences from island to island. Characteristics including venom composition, pattern, color, size, shape and behavior vary among five areas of Naka-ryukyu: Okinawa, isolated islands located around Okinawa, Tokunoshima, Amami Oshima, and the Takara and Kodakara Islands. In particular, the strong myonecrotic factor found in the venom of habu living on Amami Oshima and Tokunoshima is quite conspicuous.

Vividly colored “golden habu” found on Amami Oshima.

According to historical records, local municipalities have been putting bounties on habu since the end of the Edo period. Back then, one habu snake would bring around 1.5 kilograms of rice on average. These days, the municipalities will pay 3,000 yen per snake, and the number of habu caught on Amami Oshima totals 15,000 annually.

As a venomous snake that local people can readily encounter in daily life, habu is still an object of fear today. On Amami Oshima, around 20 information sessions are held each year at schools and community centers on what to do if you are bitten by one. Participants are shown live snakes and specimens such as shedded skins and fangs, while also learning about the habu’s behavior, characteristics of its venom, necessary first aid, medical treatment at hospitals and snakebite prognosis. By providing the public with the latest information, these sessions aim to promote the coexistence of two types of inhabitants on the island: people and habu.

Note: This article was originally printed in Tansei 35 (Japanese language only). All information in this article is as of September 2017.