Societies with and without feral cats Is fertility control completely justified?

Societies with and without feral cats

Is fertility control completely justified?

According to Professor Tomoji Onozuka, who has studied the conditions of feral cats in various global locations, the world can be divided clearly into places where feral cats exist and places where they don’t. Are feral cats or pet cats happier? Are humans happier with feral cats or a feral-cat free world? This economic historian, who has a corner reserved for cat books on his bookshelf, explores a difficult issue that transcends the realm of economic history.

Cats and Economic History

By Tomoji Onozuka By Tomoji OnozukaProfessor, Graduate School of Economics |

Nagasaki City has many feral cats and many elderly people. As seen here, it also has a one-eyed semi-feral cat that wears a collar. Pictured are four cats in the “cat square” on the narrow road that passes from Tojin Yashiki-ato to Higashi Yamate.

The world can be divided into societies that have feral cats and those that don’t. Among the latter, with the exception of those in extreme environments where cats could not survive anyway, such as polar regions and deserts, societies without feral cats have actively sought to eliminate them. In concrete terms, the United Kingdom and Germany currently have almost no feral cats. Feral cats still exist in Mediterranean coastal nations, such as Italy, Croatia, Greece and Egypt, as well as most Asian nations. However, a gradually increasing number of urban areas in Japan and Italy are now seeking to get rid of feral cats.

The relationship between humans and cats began when humans moved into agriculture and started cultivating and storing grains and pulses (legumes). This caused rats and small birds to gather on the arable land and near human settlements, which, in turn, attracted predatory wildcats into human environments as well. Thereafter, Felis catus, or domesticated cats, survived by catching the rats and birds that ventured into croplands and human settlements, or by eating leftovers from human meals or ritual food offerings left on altars. For that reason, the principal means of survival for the cat within the human-cat relationship was to live like a feral cat within the human environment, walking around freely with relative independence and catching its own food.

Taking into account this long history of cats and people, rather than defining a feral cat as a complement to the pet cat (owned and protected by humans), it might be more appropriate to focus on the cat’s ecology and define it as a cat that can act independently from humans outdoors. Under this definition, the feral cat category would also include a so-called semi-feral cat, which spends part of its time being fed in a human dwelling, resting and acting like a pet cat, and part of its time walking alone outside, interacting with other cats, and catching its own food (small animals). Among these semi-feral cats, there are some particularly bold ones that secure their freedom of action by wandering through multiple houses, arbitrarily accepting the care of many different people. Of course, the feral cat category also includes fully feral cats that don’t have a human dwelling to enter. Semi-feral and fully feral cats share a common ecology in the fact that they can wander alone outside and interact with other cats. This ecology is different from that of the pet cat, or "house cat," which lives entirely under the protective management of humans.

Five cats in the "cat shelter" close to a horse-racing track on the outskirts of Trieste, Italy. There are lots of elderly people around here, too.

The history of domesticated cats is roughly the same as that of feral cats. However, "advanced animal welfare nations" such as the United Kingdom and Germany started to domesticate feral cats from the middle of the 20th century with the aim of eliminating "unfortunate cats without an owner." As a result, feral cats all but disappeared there within the space of half a century, proving that a decade is ample time to eliminate feral cats from a specific region by thoroughly capturing and spaying or neutering all cats considered to be feral under the abovementioned definition.

In recent years, we have seen a similar joint movement by local residents and authorities in the UTokyo neighborhood of Hongo inspired by the same motivations, and feral cats have mostly been eliminated from the area. However, while less obvious than in the past, generations of feral cats continue to survive on the Hongo Campus, and you can sometimes spot the valiant silhouettes of feral cats jumping over the wall in the middle of the night to venture forth onto the Hongo streets.

I think one factor exacerbating recent urban cat problems is that elderly people living alone overfeed feral cats, resulting in an excessive increase in their numbers, but that is more a product of our society rather than a feral cat issue. If feral cats are a mirror reflecting people and societies, is the artificial restriction of their reproduction entirely justifiable? Ask yourselves, could you do the same thing to crows or sparrows?

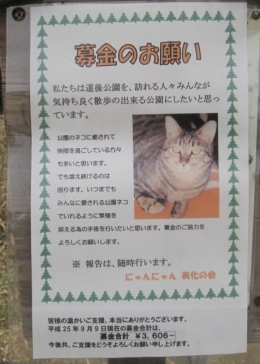

While not a residential area, this poster in Dogo Park, Matsuyama (Ehime Prefecture) advertises a movement to "beautify" parks by addressing the issue of feral cats.

* This article was originally printed in Tansei 37 (Japanese language only). All information in this article is as of September 2018.